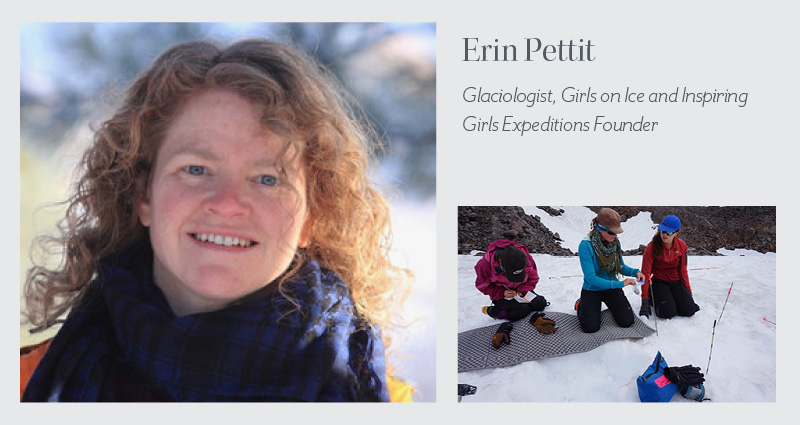

Photos: Girls on Ice (L), Cecilia Marrinan (R)

“The glaciers are trying to tell us something,” said Erin Pettit in a talk at the 2015 TEDWomen conference. She ought to know. A glaciologist and assistant professor of geophysics and glaciology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Pettit has spent more than two decades studying glaciers and glaciated landscapes in order to better understand and predict climate change and rising sea levels.

As an undergraduate studying mechanical engineering, Pettit was fascinated with fluid motion. An earth science class sparked an “aha” moment in which she realized that mechanical engineering provided an understanding of the physical processes that control how landscapes work. This led her to pursue graduate studies—and ultimately a career — in geophysics and glaciology. Pettit’s research has since shed light into the processes behind melting ice, and led to fascinating discoveries, such as the underground source of Antarctica’s famous Blood Falls, an iron oxide tainted blood red stream of iron oxide-tainted water that flows down the side of a glacier. Pettit has conducted groundbreaking research involving the recording of acoustic signals from melting, cracking, and calving ice using underwater microphones. These explorations of underwater soundscapes helped reveal the role of warm ocean water in eroding ice from below. In 2013, she was named an Emerging Explorer by National Geographic.

Pettit was recently selected to help lead a five-year, joint US-UK study of one of the most unstable glaciers in Antarctica, the Thwaites Glacier. The International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration will engage more than 60 scientists and students in one of the most detailed and extensive examinations of a massive Antarctic glacier ever undertaken. Pettit refers to it as “an observation and modeling blitz,” and she is very excited about the new science and information it will yield. “We’ve been watching this glacier evolve with satellite imagery,” she said, “I’m very eager to get on the ground and get some better measurements to really understand this system.” She is also excited about an upcoming move to join the faculty of Oregon State University’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, where she will have the opportunity to study smaller glaciers and permanent icefields in her home mountain range, the Cascades. “There is a huge relationship between these glaciers and the whole downstream ecosystem,” she said.

Pettit’s work has enhanced understanding of some of the invisible processes of a changing climate, but her research is not the only thing influencing fields related to ecology. In 1999, she created Girls on Ice, a program designed to cultivate girls’ scientific, physical, intellectual, and leadership abilities through expeditions where they explore, learn about, and conduct research on glaciers. Girls on Ice has since expanded under the umbrella of Pettit’s Inspiring Girls Expeditions, a non-profit organization that offers unique, tuition-free wilderness expeditions for girls ages 16 and 17. The girls learn about glaciers and conduct field studies in alpine and marine environments. In the process, according to Pettit, the girls gain critical thinking skills, an appreciation for science outside of the classroom, a new perspective on leadership, and the confidence and courage to push themselves out of their comfort zones and do whatever they want in life. Many expedition participants have chosen to pursue careers in science, including one Girls on Ice alumna who is currently in grad school studying glaciology and climate science. With Erin Pettit as role model, there will likely be many more young women embarking on that path.

When asked if women bring a unique capacity to the field of glaciology, she responded, “Although this ability is not limited to females, women are very skilled at ensuring that in these challenging environments, all field team members are safe and feel comfortable. I also believe that women have played an important role in cracking open the door of a traditionally white male research field and opening it to more diversity.”