You have been involved in the dam removal movement in the United States since its infancy. What set the stage for the birth of the American dam removal movement?

Early on, our policies and regulations started setting the stage. As early as 1934, the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act, [which required consideration of environmental impacts and incorporation of fish and wildlife conservation measures into Federal and Federally permitted water development projects.] made us start balancing issues. Of course, you can’t understate the importance of the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act in protecting our rivers and our threatened species. There was also the Electric Consumers Protection Act of 1986, which greatly increased the importance of environmental considerations and the role of State and Federal fish and wildlife agencies in the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission hydro-electric dam relicensing process. These all set the stage because dam builders and operators now had to start considering the environmental impacts, and in some cases incorporate fish passage.

Laura Wildman

It also started becoming more obvious that the addition of a fishway at a dam was not always the solution to restore effective fish passage, and that the cost of putting a fishway on a marginally economic dam didn’t make sense. That’s really when dam removal started being considered more in earnest. The discussion to remove the Elwha River dams [in Washington state’s Olympic Peninsula] was a huge milestone. The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe began to protest the loss of their fishing rights promised to them by federal treaty and by the 1980s the tribe was calling for the removal of the dams, decades before the dams finally came down in 2011-2014. It was the largest dam removal project in American history, and it really got the ball rolling. In 1990 the National Parks Service biologists working on the Elwha River dam removal effort published a report documenting the removal of multiple dams in California and the Pacific Northwest from 1922-1990, in an effort to show that the concept of dam removal was not as new and untested as others might think. Perspectives were starting to change by the time the Edwards Dam was removed in 1999, marking the first time in history that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission denied the relicensing of a hydro-electric dam and required its removal. [The removal of the Edwards Dam established the authority of federal organizations to order the removal of obsolete dams in order to restore significant river ecosystems.]

Removal of the Glines Canyon Dam on the Elwha River began in September, 2011. Photo by J Daracunas, Shutterstock

Who have been some of the key players in the American dam movement?

I would say that one of the most inspiring players of the time was Bruce Babbitt, who was Secretary of Interior from 1993 to 2001. He really changed the whole dialogue. In a speech he delivered to the Ecological Society of America in 1998, he explained how, “dams that were clearly justified for their economic value gradually gave way to projects built with excessive taxpayer subsidies, then justified by dubious cost-benefit projections.” He’d even go out to dam removal project sites and bring a sledgehammer with him. On the day that the Edwards Dam was first breached Babbitt commented that in regards to the dam removal “on the Kennebec River, the age, location, huge environmental costs, and low generation at Edwards made it a relatively easy call, for removal.” To have someone at a high federal level be a strong proponent of removing dams that no longer made sense, made a big difference. He gave a lot of credence to the concept of dam removal as a sensible alternative at some sites.

There were also a lot of heroes who were more behind the scenes. One would be Meg Galloway, who was head of Dam Safety with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. She was a leader in taking out dams that no longer made sense and in getting people to understand that removing a dam is also part of dam safety and that repairing dams that no longer served a purpose did not make sense. Brian Winter, a biologist with the National Parks Service, was blazing a path for all of us who followed as he thought through many of the challenges that arose during the preparations to remove the Elwha River dams. Scott Carney, who was then with the Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission, was a real leader in getting small dams out all over Pennsylvania. Ron Kreisman, an environmental lawyer, was instrumental behind the scenes in all of the large, negotiated FERC settlements in Maine that have led to incredible ecological uplift and restoration of historic fish runs on the Kennebec, Penobscot and Presumpscot rivers.

Laura (center) and two of her dam removal heroes and collaborators, Amy Singler of American Rivers (L) and Eileen Fielding of the Farmington River Watershed Association (R)

American Rivers played the leading role in the dam removal movement in the United States. I was personally inspired and led by Margaret Bowman, who initiated American Rivers’ Dam Removal Program in 2000, after the critical success of the Edwards Dam Removal which she and her team helped shepherd. In addition, NOAA was also an important player. The agency’s 2005 Open Rivers Initiative provided funding that really made a difference. We then started seeing other nonprofits like The Nature Conservancy and agencies, like the US Fish & Wildlife Service, take on additional leading roles.

In what major ways do you think the U.S. dam removal movement has evolved since its birth?

When I very first got involved in the mid-1990s, dam removal was considered crazy talk. It was like saying, “Let’s remove the sun from the sky,” or “let’s remove Niagara Falls.”

A lot of people equated all dams with Hoover Dam or mistakenly thought they were waterfalls. My grandfather designed and built dams for a living, and dam builders were the fireman of their day. They could do no wrong. They were providing drinking water, flood control, navigation, and power, which were all good things that helped people. That had been the only dialogue related to dams. We hadn’t heard anything about the negative impacts of dams, both ecologically and from a human safety perspective. Even though there had been some catastrophic dam failures, we didn’t have a global press that spread the news instantaneously and broadly. We never heard about the native fish species that were completely eradicated from countless river systems. We didn’t connect the continued degradation of water quality with the stagnant, stair-stepped river systems we were developing as more and more dams were built. Nor did we understand the dramatic impacts that result when the natural sediment transport processes are blocked by a dam. Since the dialogue had only focused on the positive things we gained until that point, the suggestion of removing a dam seemed like crazy talk.

It was like saying, ‘Let’s remove the sun from the sky,’ or ‘let’s remove Niagara Falls.’

I still remember the first time I mentioned dam removal to my mother and my doctor, on two separate occasions while I was working on a project examining the potential of dam removals on the Naugatuck River in Connecticut. They each said, “You can’t remove dams. Those are for flood control!” There were huge floods on the Naugatuck in 1955 but the dams on the river were mill dams and had nothing to do with flood control. In fact, they exacerbated the flooding during the 1955 floods. As debris built up behind them, water built up even more. Then the debris jams at each dam blew. It was just a mess. Flood control dams went in on the Naugatuck River after the 1955 floods. And flood control dams don’t look anything like regular dams. For the most part they’re empty. This allows them to fill up when needed and attenuate peak flows.

So that was really kind of the biggest transition in the movement—going from any mention of dam removal generating a response like, “You can’t remove dams. They are all beneficial and serving a purpose” to the American’ public’s slow realization that many dams no longer serve a purpose and dam removal is a viable option, especially for obsolete, and antiquated dams.

The Thomaston Dam, which provides flood protection in the highly industrialized and densely populated Naugatuck Valley. ©USACE

How complete is that slow realization? Do misconceptions about dams and dam removal still get in the way of progress?

Things are changing but there are of course still may misconceptions regarding dam removal. One is that if you are pro dam removal you must be anti-dam. That’s just not the case. Most of the dams being removed are dams that no longer serve a purpose and have ecological impacts on the system, or safety or liability issues. I don’t know of any people that are trying to remove actively used and maintained water supply, flood control or navigation dams, or hydro-electric dams that make economic sense. The dams that are being removed no longer serve an economic purpose, or the economic justification is so marginal that it does not justify the continued impacts or maintenance of the dam.

Plume & Attwood Dam on the Naugatuck River, serving no purpose Photo by Laura Wildman

The idea of removing a dam seems like a massive and complicated undertaking. What advice do you have for people who are interested in removing or looking into the feasibility of removing a dam in their community, but don’t know where to begin?

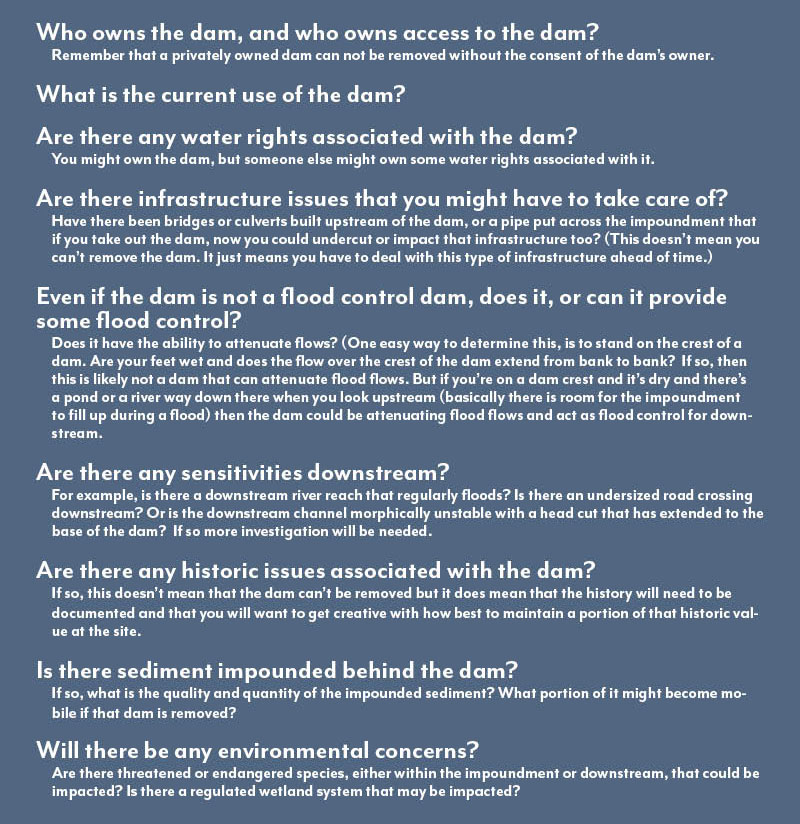

Reach out to some of the experts. Those experts can be found at your local Dam Safety offices, and in nonprofits like American Rivers, The Nature Conservancy, or your local river/watershed association. You can also find experts at ecological consulting firms like ours. You’ll want to understand issues related to safety and ecology, and these experts can be very helpful. I also have several questions that are important to ask when you are contemplating the removal of a dam:

In addition to asking those questions, you have to talk to the experts and determine if there might be funding resources available. There are grants for removal in a lot of cases, especially if the removal has ecological benefits, so don’t necessarily assume that you have to come up with every last dollar for the project yourself.

It is also critical to integrate the community into the decision-making process. Even if you’re the dam owner and you feel like they shouldn’t have a say, they do have a say, and our regulatory process allows that. You need to understand what their concerns might be and work to collaboratively find solutions.

Laura (left) Amy Singler of American Rivers (R), learning in the field from other completed dam removal projects

Do you have any advice to offer on communicating with community members to learn about their concerns and help them understand the benefits of dam removal?

The first time you go to a community to talk to them about a dam, just go to listen and learn from them, rather than give information. Community members know more about that particular place than you do, and they can be a valuable resource. They may tell you, for example, that “In the flood of blah, blah, blah, the dam over topped or a downstream culvert breached.” Or they may tell you that the dam was replaced in the 1970s, and there’s actually another dam just upstream of the dam you intend to remove. There’s a lot you can learn from listening to the local community and involving them in the dialogue right off the bat. As you gather more information, hopefully you can help address some of their concerns, even when they might be misconceptions. Help them understand that removing a dam isn’t going to, let’s say, drain the entire river. Or result in permanent mud flats. Those are typical misconceptions. It’s good to show people a vision of what the site will look like post dam removal.

Laura, speaking with community members

These are always going to be tough discussions because even once all the facts and information are on the table, there are certain issues that are purely subjective, and you need to understand that not everyone is going to agree. There are always going to be some conflicts when discussing rivers, dams, fish, and safety. There always have been. There were conflicts when the dams first were built, and there have likely been conflicts each time a new decision point arises.

I have researched many of these historic decision points relating to dams. We have different reasons for making decisions at different times; values and needs change over time. At the time when a lot of mill dams went in, local communities needed the services that the mills provided, processing timber, grinding grain, and providing mechanical power and process water for local industries. The dams made sense then and were often utilized seasonally such that the rivers could run free during the fish runs. Our needs and values transitioned during the Industrial Revolution, and sadly rivers started becoming industrial sewers and rivers were blocked year round by the industrial dams. Unfortunately, during that time period, we often forgot the value of rivers as a public trust resource. And that’s when we saw rivers catching fire and changing color every day—no longer drinkable or swimmable. Today we are in yet a different place, where we’re doing a slightly better job balancing the uses and protections of our river systems, but we still have a way to go.

You have been involved in hundreds of projects involving the consideration of dam removal. In a recent Wednesday at the Watering Hole webinar, you shared some of the most common mistakes in dam removal. Has there been one standout lesson learned about dam removal from your experience?

[To view Laura’s webinar, see the Glossary & Resources section of this issue, or visit Rhizome, Biohabitats’ blog and video hub}

I started the Watering Hole talk by presenting the number one mistake: not removing a dam. We must avoid the knee jerk reaction of saying “we can’t remove this dam” when we run up against our first difficulty or complication in a dam removal project. We cannot stop in our tracks and say, “Let’s put a fishway in instead.” A fishway is a partial patch. Sometimes it is a necessary patch, but fishways do not restore natural river processes and require extensive maintenance to stay operable.

Fish ladder near a dam on the Valge jõgi, Harjumaa, Estonia Photo by M. Pakats, Shutterstock

Another example is when there are contaminated sediments behind the dam. People think, “It’s going to cost millions to remove this dam because there are contaminated sediments behind it, so we cannot remove this dam.” But let’s ask ourselves, do we really want a contaminated sediment dump to stay located in a dynamic river system, especially with climate change, and increased flood peaks? Now that we know there are contaminants behind the dam, that should be all the more reason for that dam to be considered for removal and for us to address the contaminated sediments in a controlled manner, especially if the dam is not being adequately maintained. It might make it cost-prohibitive at the time, but it’s all the more reason to try to look for a long-term sustainable solution and get those contaminants out of the river system.

For the most part, the dams that get maintained are the ones that still have economic value. When we decide not to remove a dam, we must ask ourselves, “Who is going to maintain this dam from now on?” Or is our decision just to let the dam breach on its own over time, and if so, what kind of risks does that mean for the downstream population? And what is the price tag that we pass down to future generations that will need to address the problem?” All of these things need to be considered before we walk away from a site.

Do you have a favorite dam removal project?

I love being involved in the removal of dams because unlike other projects, a successful project is often impossible to identify on the landscape. When you go out to my grandfather’s project sites, you see these huge monoliths he left behind (admittedly serving active water supply purposes). But when you go out to my project sites, it just looks like a river doing its thing, and I love that. That’s what I love in general about removing dams from rivers. But I do have a favorite project, and that was my first. It was the Naugatuck River and I have been involved in helping to restore that river for 30 years now.

The Naugatuck River wouldn’t be an obvious choice for a lot of people because it was a highly polluted, industrial river. It was hard hit by the Industrial Revolution—just stair-step dams and industry all the way up. But way before that, the Naugatuck Valley was a steep, rocky, bedrock-controlled valley with the Naugatuck River swiftly flowing through the center. It is a much more linear system than a lot of river systems and it runs north to south in Connecticut. I imagine that this river just teemed with migratory fish back in the day. According to historical reports, Native American tribes along the river would gather by bedrock pinch points and collect fish during their upstream migration. As a matter of fact, in Algonquian, the word “Naugatuck” means “the lone tree by the fishing place.” The “fishing place” was in reference to the bedrock falls in Seymour that was a critical pinch point and the most important fishing location for the tribes in the region. The town of Seymour used to be named Amaugsuck, which translates to “the fishing place where the waters poured down.” I just can picture that lone tree by the falls and the fish backing up as they took turns leaping over the falls.

Sadly, many decades later, my father-in-law used to talk about how they’d roll up the windows in the car when they would pass over the Naugatuck River because it smelled so bad. He would say that they could always tell what color sneakers were being made in the nearby factory by the color of the water in the Naugatuck River. It was so polluted that most of the buildings along the Naugatuck face away from the river, with no windows looking out over it.

A cemetery along the Naugatuck River in Seymour, CT. Photo by Joe Mabel

I was raised in a town at the edge of the watershed, and to have been involved in its restoration and watch the river rejuvenate over the course of my career, has been incredible. Today, the towns are turning back towards the river. There are people kayaking on it, and there are river festivals along it. It has a long way to go, but it has been restoring itself with the help of some amazing volunteers and efforts to remove dams and trash, improve water quality, and plant vegetative buffers.

Laura at the Naugatuck River

I always say that it’s my favorite river because it’s the river that needed me the most, you know?

It is interesting to compare the highly impacted Naugatuck River to one of the most pristine rivers in Connecticut, the Farmington River. The Farmington River flows through several towns, and when you go onto these town websites, the river is either on their town seal or highlighted on their webpage. Cars you pass have kayaks or canoes loaded on top, and there are multiple fly fishing shops along the main streets. It’s very clear that all these towns are river towns, and that the Farmington flows through them. And all the buildings, houses, and restaurants face towards the river. And the Naugatuck had always been the opposite of that. You would never see photos of the river on the town’s websites and the only town seal that showed the river, that of the Town of Seymour, highlighted the dam that covered the historic falls. But things are transitioning as the river is revitalized and more recently, Seymour changed its seal to show the historic falls—”the fishing place where the water poured down.”

Do you have any final words to share with Leaf Litter readers?

I’m a loud person. I have a big voice and I’ve always felt like there was a reason for that. Rivers can’t speak for themselves, so it’s my job to speak for them. I would just encourage Leaf Litter readers to do the same. The more voices that join in and advocate for rivers, the louder we will be and the harder to ignore!

Laura holding the World Fish Migration Foundation's "Happy Fish" symbol.