Katherine Lieberknecht, Ph.D.

Katherine Lieberknecht did not intend to be an academic. After witnessing the ranches and bluebonnet fields of her childhood home in Austin, Texas become paved and converted into big box developments in the 1990s, she wanted to go out and fix the problem of sprawl. Early in her career, she did just that by working in conservation for the Finger Lakes Land Trust. Though the work was rewarding and particularly important during a time of reduced federal funding for open space conservation, it left Katherine dogged by a question: How can we create access to nature for everyone, not just people in communities with the resources to create and fund land trusts? Her pursuit of this question ultimately led to a Ph.D. in City and Regional Planning from Cornell University. Today, Dr. Lieberknecht is assistant professor in the School of Architecture at The University of Texas at Austin, where she teaches courses and conducts research related to the planning of urban ecology, water resources, green infrastructure, agriculture, sustainable land use and resilience. She also serves as chair of Planet Texas 2050, The University of Texas at Austin’s first grand challenge research program, and faculty lead for the Texas Metro Observatory, a Planet Texas 2050 research project. We were thrilled to have the opportunity to chat with her about the concept of “ecological wisdom” and its application to urban planning.

In the paper “From smart cities to wise cities: ecological wisdom as a basis for sustainable urban development,” which you co-wrote with Dr. Robert Young*, you compared two different approaches to urban planning which share the objective of reducing environmental impact: smart cities and wise cities. Can you briefly explain these approaches?

The smart cities approach to urban infrastructure, planning, and management is focused on the wealth of real-time data we now have through communication and information technology networks. It aims to harness that data, analyze it in real time, and use it to improve sustainability in human settlements, typically by an efficiency model. For example, if we can better track water use and access better data about how and why people use water, we can better tailor programs to improve water conservation and reduce overall water use. The smart cities approach is basically trying to catch a ride on the flood of data we now have in many places around the world and use those data streams to better inform sustainability decisions.

The wise city or “ecological wisdom” approach is also focused on data, but it includes data that reaches back into the past. Ecological wisdom looks at current and historical information that is focused on ecology. It includes what we learn from ecosystem flows and functions, as well as what we learn from the people part of an ecosystem—the governance we establish, the decisions we make, the built environments we create, etc. The idea is to try to find durable, time-tested, context-specific strategies for sustainability and resilience that include information about the social and ecological systems of a place.

I realize that ecological wisdom is a relatively new concept, but can you give us an example?

An accessible example of the ecological wisdom approach is the role of vernacular architecture in a place. For example, where I live in central Texas, it is always very hot in the summer. If you look back in time, before the advent of air conditioning, you learn that people used vernacular architecture to cope with the heat. This architecture created breezeways and used household design to enable people to shut out the heat in the afternoon and open up the house in the evening. It used large, wide roofs that created porch overhangs for shade as well as ample cover for rainwater harvesting. That’s a small example at the household scale of an ecologically wise approach.

The Espada Aqueduct, part of the San Antonio Water System, dates from the 1700s and was/is part of the acequia system. It still actively moves water, which is used for farming in southern San Antonio. Photo: Katherine Lieberknecht

At a larger scale, the structure of San Antonio’s water utility, the San Antonio Water System is based on ecological wisdom (although they may not use that phrase). They are located right along the border of the Hill Country, where water soaks down through karst limestone into shallow aquifers, hits a topographic change, and gets pushed up out of the earth via springs. When San Antonio first became a municipality, instead of having one place where they would get, treat, and distribute water, they created a public water system based on multiple springs across the city because they already had a diverse water supply embedded into the landscape. One hundred years later, their water system is still based on that model. They continue to mimic that diverse portfolio of water systems as a way to better transition to a dryer, hotter climate with a growing population.

The wise city approach is not necessarily antagonistic to a smart city approach. In fact, it could be complimentary. The amazing, real-time data flows of the smart city approach could easily be folded into an ecological wisdom approach.

I’d like to discuss such a possible combination, but first…when and where did the concept of “ecological wisdom” originate?

In 2014, a planning scholar named Wei-Ning Xiang invited scholars to China for the first International Symposium on Ecological Wisdom. He wanted to explore a planning concept which, in his eyes, was based on several different streams of knowledge, including bioregionalism, deep ecology, indigenous knowledge, and Chinese traditions of respect for the past. After that original symposium, there was a second symposium hosted at UT Austin in 2016, an EcoWISE series of books is being published, and there has been a special issue of the journal Landscape and Urban Planning. It has really just been bubbling up in the past decade.

Let’s talk about combining elements of smart city and ecological wisdom approaches. When it comes to urban planning, what might that look like? How might ecological and cultural wisdom be combined with smart technology to foster the co-evolution of social and ecological systems and enhance the resilience of an urban area?

I am currently working on a grant proposal with the City of Austin and a local non-profit, Go Austin/Vamos Austin that has required me to ask this same question. We have pretty severe flash flooding problems in Austin. The City has a decades-long voluntary buy-out program, where people who live in the floodplain can sell their home and move, but that has been disruptive and created situations where there is vacant land in the middle of a neighborhood. The City wants to create a new vision for this riparian floodplain land, and they want to do it together with a community that has historically not been given equitable resources or attention. They want to come up with a way to protect the floodplain while also delivering benefits to this community like mitigating heat events, increasing opportunities for mobility, and providing safe routes to school. Because we’re in Austin, which is a high-tech town, we’ve been brainstorming ways to use of all of the data that is or could be available, such as differential heat maps that show how extreme heat events are felt differently by different populations, increased demographic data to help us better identify and help vulnerable populations, and increased sensor data to provide real-time information about flooding upstream to help us model best when floods will happen in this area. We have been discussing how we can best use the opportunity of all of these new data streams in a way that is respectful of the local context of ecological and social knowledge, and knowledge of the past settlements in the area.

You are the chair of an initiative called Planet Texas 2050, a multidisciplinary effort to understand the interconnectedness of water, energy, urbanization, and ecosystem services in the state of Texas. Can you tell us more about that?

Academic researchers are often stuck in silos, focusing on our sub-sub-sub disciplines. About three years ago, UT Austin’s new Provost (Dr. Maurie McInnis) and President [Dr. Gregory Fenves) started the Bridging Barriers research initiative, a grand challenge research program, to provide incentive for university researchers to cross disciplinary boundaries while also directly applying their research to a real-world problem. Faculty and researchers across the university helped determine the three focus areas for the program: health, AI, and resilience. Planet Texas 2050 is focused on resilience.

We know that over the next couple of decades, a lot more people are moving to Texas and we will have many more extreme weather events. Thinking about those changes and the four systems that you mentioned, we want to help ensure a more resilient Texas by 2050. We define resilience as “safe, healthy, just, and ecologically and economically vibrant.” We are trying to integrate history, lessons from the past, and the knowledge bases of diverse disciplines to work with communities to develop solutions that are applied, durable, and useful. We have been doing research for about a year. Planet Texas is an eight to ten-year program. We initially funded eight projects, involving 140 researchers, and we are going to bring more on board this year. The modeling and data integration piece are pretty innovative. If we are able to pull it off, there will be uses for those systems for other places in the U.S and around the world who are trying to harness and combine all of these disciplines and data sources to focus on resilience.

A community meeting in the Montopolis neighborhood in Austin, where a Planet Texas 2050 partner and local nonprofit, the Austin Community Design and Development Center, facilitated the sharing of local knowledge. Photo: Austin Community Design and Development Center.

What research do you think is most urgently needed to advance the practice of ecological wisdom and its application of urban planning? In other words, if a big pile of money fell into your lap, what would you do with it.

We still need to do a lot of knowledge production, but there is a lot of knowledge that is not being applied that could really improve planning and management processes in cities and other human settlements. There is so much data, but it doesn’t always get into the hands of people who can use it, and it is not always translatable. As part of Planet Texas, we’ve been creating a data and communications platform called the Texas Metro Observatory. It is not just for researchers. It is for everyone. It is a data repository, but it also tells stories with these data through visualizations, maps, and short reports. It increases accessibility to all of this amazing information we already have. So continuing to make data more accessible, easier to digest, available in one place, and free is one way I’d use that money.

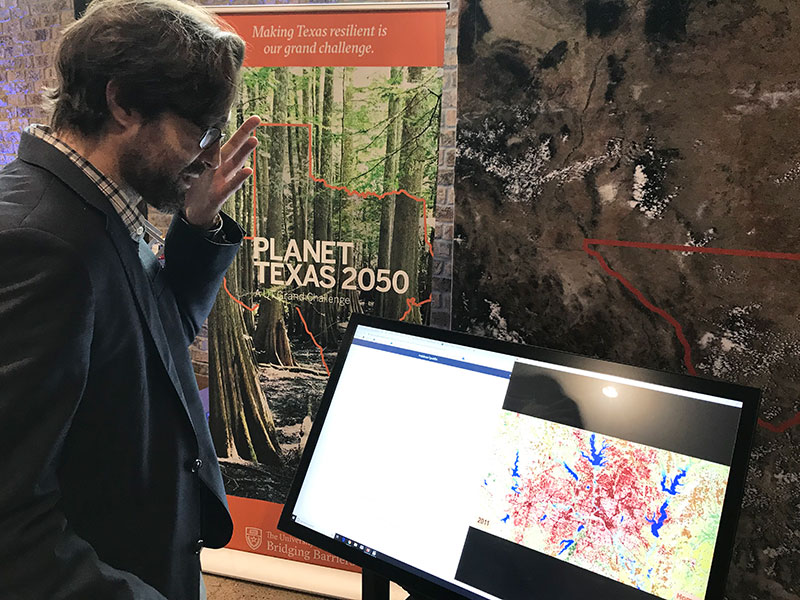

Planet Texas researcher and doctoral student Steven Richter using the metropolitan data dashboards that are the prototype of the Texas Metro Observatory platform. Photo: Jenny Nelson Gray

We have also been focused on incorporating more local knowledge or lived experience related to climate change and resilience into all of these big climate change and resilience-focused research projects. We have good climate modeling now, and although a lot of it needs to be downscaled to the city scale, that work is being done. The gap that is not yet being addressed is spending more time with local inhabitants in places that are already experiencing climate change and finding out what they sense, what they know, and what matters to them. In many cases, the impacts of climate change are exaggerations of previous patterns, so learning what strategies people have used to deal with similar extreme events in the past, and what people envision needing in recovery periods can be very useful. We have been playing with ways to improve that bidirectional resilience information exchange, so it’s not just scientists plopping down pieces of knowledge and models into communities and saying, “Hey, use this stuff to make more resilient places.”

One of my favorite Planet Texas research projects is called Texas Water Stories. It involves geographers and sociologists going out all over Texas and interviewing people about their experiences with water. They ask people questions like, “What do you remember droughts feeling like when you were little, and do they feel different now?”

Planet Texas 2050 researchers Suzanne Pierce and Katherine Lieberknecht at an event where they shared research with the Texas Legislature (and Bevo, the UT mascot). Photo: Jenny Nelson Gray.

In the introduction to your paper comparing the smart city and wise city approaches, you note that in developing countries, where birthrates are declining and median age is increasing, there are fewer tax dollars to support improvements to cities. Sometimes a lack of financial resources can spark fresh, new thinking. Have you seen any interesting (or eco-wise) planning work done in such cities?

The first strategy we think about in planning for cities dealing with declining populations and tax bases, is to bring on any new infrastructure in a distributed way, so you can turn it off and on as needed and you are more prepared for an uncertain future. Although it is hard to imagine that the growth rates in Texas will not continue, that could happen if we run out of water, have repeated wildfires, or experience a certain political change. Having distributed, site-specific, site-sustaining, closed-loop water systems is an example of a planning strategy for that situation.

Informal settlements in developing countries are difficult and inequitable places to live, but they often also offer many lessons about eco-wise use of limited resources, such as water and land for food production, which can provide guidance and inspiration for other places around the world considering how to make more resource-efficient places. For example, in informal settlements without centralized potable water supplies, residents are much more careful with costly potable water, substituting other sources, such as rainwater, for non-potable uses such as irrigation or washing. In contrast, places like where I live in Austin, we use potable water for pretty much every water use (with the exception of some use of reclaimed wastewater for municipal or commercial irrigation). When Austin had a boil-water advisory for about a week last fall, due to unprecedented flooding that overloaded sediment into our water treatment plant, Austin residents had to either purchase drinking water or boil water before using for potable water uses. The day after the boil-water advisory was announced, my water resources planning class spent most of our class time discussing how much we take a seemingly endless supply of potable water for granted, but how literally overnight, many of us were quickly trying to figure out ways to prioritize potable water uses. These are the types of constraints that residents in informal settlements deal with every day; an ecowise approach towards the development of potable water infrastructure in these areas would combine this local knowledge of how to carefully conserve potable water by better matching lower quality water supplies with non-potable water uses, such as flushing toilets or irrigation, rather than following the pathway that US cities have used for about 100 years, which is using potable water for all uses, regardless of need. Informal settlements need secure, affordable, safe and clean potable water supplies, but it may be possible to build these new water systems in a way that allows greater flexibility in terms of better matching particular water uses with different water sources, for the purpose of saving water as well as saving energy.

Then there is the flip side. Cities that have lost population suddenly find themselves with space to do things differently. Rust Belt cities in the U.S. have many great examples of repurposing empty land for ecologically wise uses, like food production, open space recreation, and—increasingly—flood protection.

In that same introduction, you quote the World Bank, which says that “population and economic growth are pushing the limits of the world’s finite water resources.” Yet, based on what I read “Ecowisdom and Water in Human Settlements” a chapter you contributed to the book Ecological Wisdom: Theory and Practice it seems like water—when both visible and variable-—holds great promise as a planning and design tool for rapidly growing cities, particularly those on the front lines of climate change. Can you talk about that?

Humans have, unfortunately, achieved mass appropriation of water resources. Because of that, in addition to climate change and changes in evaporation and precipitation rates, there is real water scarcity happening. That is true. But it is also true that because water is still relatively visible (e.g., rain coming down from the sky, creeks that have not been buried, waterfronts) in a way that many other ecosystem flows in human settlements are not, it can be a conscious, daily reminder of our connection to, dependence upon, and stewardship relationship with nature and ecosystems. In theory, the scarcity of water should make us pay attention to it even more. That certainly is the case here in Texas during drought years. Concern about water is pretty much the only environmental issue that unifies all Texans.

In the book chapter, you discuss two strategies used by two different cities in Texas to protect ecosystem services and enhance resilience in climate-impacted cities in a way that fosters human cohabitation with other forms of life in the urban ecosystem. You mentioned San Antonio’s water strategy earlier, but can you tell us about these two strategies, and what can be taken from them applied to the planning of our cities?

Another way that people have been relating to water for a long time is through source protection— protecting land around water sources and using soil/vegetation complexes and healthy ecosystems to help filter out pollutants and preserve high water quality before it gets piped into a city, where usually requires less filtration and perhaps just the addition of chlorine. Before water treatment systems were created, lots of cities around the U.S. and around the world used source protection, and it remains a popular tool today, because it is so cost-effective. Hundreds of cities across the U.S. have good source protection programs, and that is definitely an ecological, wise approach to protecting the quality of drinking water.

A source protection land conservation program has protected Skaneateles Lake, which supplies water for the City of Syracuse, NY. Skaneateles has some of the cleanest water in the world. Photo: Bill Hecht.

Who has access to an ecowisdom toolkit? Ideally, everyone.

In that same article, you discuss a proposed “ecowisdom toolkit.” What is in that toolkit, and who has access to it?

Planet Drum [the organization behind the concept of “bioregions”] used to make “bioregional bundles” for each area around the U.S. Those bundles were, in a sense, ecologically wise toolkits. The idea was to include in those bundles all of the local and regional data available, along with some of the strategies that have been used in that place over time that can be adapted to future changes. We’re not there yet with Planet Texas 2050, but we are co-developing “bundles” of resilience strategies based on local knowledge, new data and climate modeling, that are accessible to decision makers, journalists, community makers, and other people thinking about these changes in different ways. That’s one iteration of what that toolkit could look like.

There are also many wonderful examples from classes I teach on water and food systems across the U.S. that have pulled together similar resource kits and shared them online. One is the Sommerville, Massachusetts’ “ABC’s of Urban Agriculture” document, which is a collection of everything a Sommerville resident would need to know to produce food in Sommerville (e.g., info about how to get a permit to keep honeybees, advice about soil safety, ways to keep compost areas rodent-free, etc.). Another is Portland, Oregon’s stormwater management website, which has sections that explain urban stormwater systems, provide how-to-guides for building residential raingardens and eco-roofs, and opportunities for small grants to pay for stewardship activities.

An ecowisdom toolkit will be different in different places, because so much may be based on local knowledge. That is why I encourage researchers and scientists to think about better engagement with local communities to build their toolkits. Given the rapid rate of change associated with climate change, time is urgent. We need to quickly to move urban (and other) systems towards resilience. One way of doing that is getting useful information out to people who are making decisions and people who are living in affected places.

Who has access to an ecowisdom toolkit? Ideally, everyone.

Earlier in your career, you worked in regional conservation. What do you think people in fields traditionally related to urban planning can learn from regional conservationists and vice versa?

One thing is that rural and urban systems are integrated, and water plays a big part that integration. Cities cannot exist without the rural hinterland and the resources we receive, take, and purchase from it. On the flip side, rural areas are just as connected to urban areas. Cities are places of job growth, hospitals, and universities. If we’re going to figure out resilience, this relationship is key. We have to convince people living in cities to respect and be willing to pay for the resources that are coming from the rural areas to support our cities. Conversely, we have to convince people living in the exurbs that cities are important places that deserve tax dollars to support the infrastructure they need. Urban planning and regional conservation are more linked than people tend to think. Although there are few governance systems that tackle that relationship, it makes sense ecologically.

*Sadly, Dr. Robert Young passed away suddenly last year. Our deepest condolences to his wife, Katherine Lieberknecht, and her family.