On the Road to Resilience: Turning Ecological Thinking into Action

By Amy Nelson

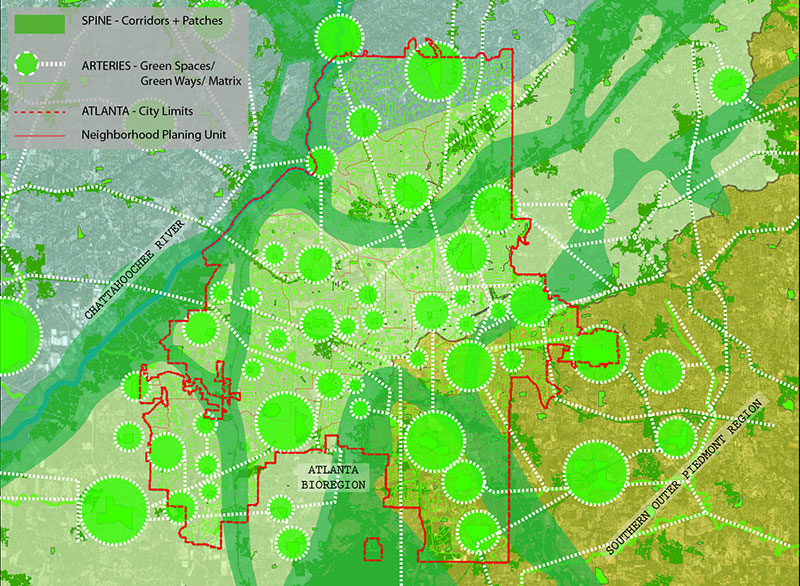

Resilient urban planning has come a long way since the UN Earth Summit first convened in 1992 to develop criteria for Sustainable Development Goals. New York City’s OneNYC2050, Atlanta’s Urban Ecology Framework, and Barcelona’s Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan are all recent examples of planning initiatives that incorporate adaptive solutions to combat climate change, population burden, and environmental degradation in cities. With innovative plans such as these receiving media attention, the world can appear on the road to resilience. But considering the city as ecosystem and incorporating that ecosystem mentality into policy still has a long, hard road ahead.

Often ecosystem services, conservation practices, and environmental justice, all critical to successful resilient planning, are pushed aside for a later date, abandoned altogether, or given a cursory glance at best in favor of immediate growth without restriction premised on the fallacy that all economic growth is good growth. As more of the earth’s population shifts en masse from rural to urban centers, many of which reside along coastlines subject to sea level rise, now is the time more than ever to slow down, take a step back, and consider the consequences of unbridled expansion and social inequity.

Effective policy, zoning, building codes and best management practices are the foundation for a resilient urban framework. Resiliency within the urban context means a city “has the capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses, and systems…to survive adapt, and grow no matter what kinds of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience” (Rockefeller Foundation, 100 Resilient Cities). Fortunately, cities are increasingly realizing that a strong resilient framework begins with a strong ecological foundation. Access to clean water, fresh air, and healthy soils; sequestering carbon and lowering urban temperatures; and addressing environmental and climate justice issues provide the basis in which to build a robust platform. However, bridging the planning to policy gap can sometimes feel convoluted, unattainable, and intentionally obfuscated for the public. But it doesn’t have to be. Following a few steps can shift ecological planning into policy implementation.

Step 1: Assess

Protecting a resource, the landscape, or a species requires a value assessment to realize how each component of the landscape interacts with the city and is crucial to its success. Establishing this ecological mindset, where the smallest element is vital to an overarching system, is the first step in developing strategy for a resilient plan.

For example, think of the trees that line the sidewalk. We look at street trees, if we look at them at all, as an aesthetic bonus. But how did they get there? Why are they there? William Penn recognized the value of trees to urban health in the 1680s, reserving sections specifically for trees in the initial plans for Philadelphia. From this recognition turned informal policy, green space has been integral to Pennsylvania’s (and other city’s) development ever since. Without this engineered green canopy incorporated into urban vehicular routes and walking pathways, cities composed mostly of concrete become heat sinks, contributing to global temperature rise; habitat for migratory birds vanishes, as well as their contributions to insect management; smog, carcinogens, and carbon dioxide pollute the air and contribute to illness; and flooding can become a problem for neighborhoods.

Conservation-minded and eco-conscious advocacy groups have the value of ecology built right into their missions, but strategic action can only be achieved when disparate groups with seemingly unrelated goals also embrace the values of ecology. Resilient and sustainable planning is often mistakenly assumed to be for the few, the wealthy, or environmental lobbyists only, but regenerative and eco-integrative policies benefit every demographic. The key is to communicate via an intra-urban network of individuals and organizations the importance of an ecological mindset to resiliency planning and how this resiliency benefits all individuals, economic opportunities, and residential wellbeing. From a values-driven and empowered public, legislation can be advocated and supported based on planning efforts.

You either work in the best interest of people or you work in the best interest of non-human entities? The beauty of ecology is you don’t have to choose.

Step 2: Educate

Initiating this equity-ecology connection starts with the advocacy groups themselves. Whether the goal is urban migratory bird habitat integration or the mitigation of gerrymandering, we’re all working toward the same future where every living being has the right to thrive without systemic interference. It’s time to combat the either-or mentality. You either work in the best interest of people or you work in the best interest of non-human entities? The beauty of ecology is you don’t have to choose. We all work together building a comprehensive solution for humans and non-humans alike because integrating biodiversity, access to multifunctional green space, and water-management solutions to climate change have expansive and long-term effects on populations extending beyond their physical boundaries and beyond the narrow sector of the environment. It’s up to organizations to view their own missions from an ecology standpoint and to educate themselves and one another on how their roles can complement a holistic strategy of multidisciplinary research that exemplifies the benefits of an environmental policy.

Apart from organizations and nonprofits, building ecology right into education curricula could begin to shift public perspective on the necessity of ecosystem services and bring the conversation of urban green space directly into the homes of urban families. Earth science is there, mathematics is there, social studies is there, but project-based curricula can bring each discipline together to see how each informs the other over time. Instituting a project-based education system where students identify and devise an approach to an issue within their own city—i.e. a green space that needs to incorporate biodiversity or the need for a restored blue-belt—exemplifies the interdisciplinary approach of ecology and instills the necessary awareness to address urban planning from each separate branch. Disparate systems talking to each other, responding to each other, and working with each other to create a sustainable, symbiotic solution for each component no matter where or how that component lives embodies the ecological mindset.

Step 3: Partner

Channeling this newfound education and finding the right direction is essential in creating an effective movement for change. Essential to being heard in the presence of the policy-makers at public meetings, conferences, and focus groups requires well-researched evidence and inclusive arguments that consider economic and cultural outcomes in addition to environmental ones. Listening to and acknowledging limitations and opposing viewpoints internally is necessary to strategize solutions with flexibility that can evolve as new data enters the fore. To ensure ecologically-conscious planning efforts have the support and guidance necessary for successful implementation, cities, their constituents, and environmental organizations need to unite their efforts to produce a strategy capable of influencing legislators.

To produce strategy between overlapping organizations, partnerships between these organizations are necessary to address environmental impacts on the appropriate scale. Activism for place starts local but never stays isolated because issues concerning the environment don’t adhere to legal boundaries. Inevitably, climate change, landscape engineering, and community migrations impact and influence macroeconomics, cultural shifts, food shortages, and disease transmission. Discovering connection between groups is the solution to connecting utility corridors, transportation routes, water management solutions, and biodiversity retrofits.

Step 4: Legislate

A state initiated effective planning to policy to partnership effort resides in San Francisco, where the California legislature listened to the research available on the declining San Francisco Bay habitat from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and individual San Francisco nongovernmental conservation entities. Rather than shrinking away from the knowledge of pollution and the ramifications of climate change, California legislature incorporated the research into legislation and introduced the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority in 2008 through the passage of the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority Act. The Act recognized the research conducted by interagency organizations, the reduced funding allocated to the preservation of wetland habitats, declared the Bay as “the region’s greatest natural resource and its central feature [which] contributes greatly to California’s economic health and vitality,” and created the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority with the intent to garner the necessary resources and ensure the protection of this unique cultural and environmental area.

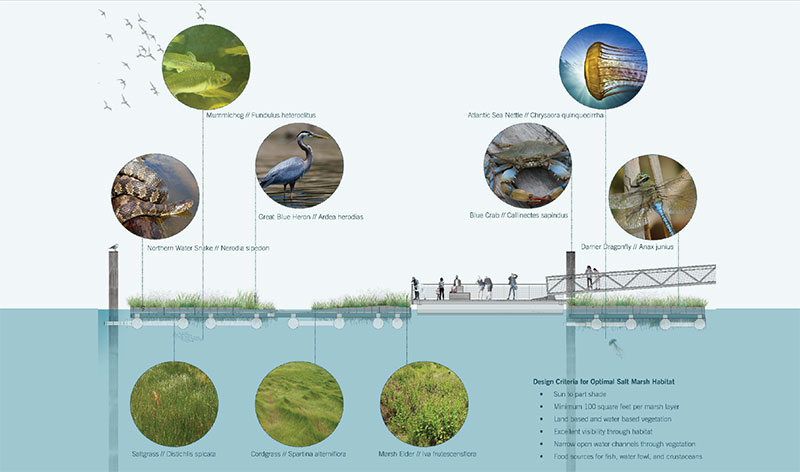

Since its creation, the SFBRA has introduced its own legislation, called Measure AA: the San Francisco Bay Clean Water, Pollution Prevention and Habitat Restoration Measure, a parcel tax able to fund Bay Area restoration projects. Residents spanning nine counties passed the measure with a 70% majority vote. Because California assessed the importance of the Bay’s ecological diversity to the area’s cultural diversity, recognized the value in its protection, and effectively educated staff and the public on the benefits of a regional authority, the state was able to introduce policies capable of supporting planning efforts into tangible project development. The legislature and the supporting communities came together to address a challenge and define its value by a policy, and this newfound institution is now able to take the first steps towards a resilient, sustainable region. Since its creation, the Bay Authority has acquired grants, and with partnerships between state, local, and nongovernmental entities has begun several wetland restoration projects, shoreline resiliency efforts, and remediation projects that also take into consideration the surrounding communities’ recreation, economic, and utility necessities.

Bridging the Connections

So what can we take away from this step-by-step process? Connectivity and integration among the local, the regional, the global, between the scientific, the historic, the health, and the conservation communities can form a deep ecological network that has a vast bed of resources to institute urban planning pathways. These pathways should also connect physically, allowing for a landscape able to accommodate multiple uses, transportation movements, utility corridors, and trade channels for humans and non-humans in all their permutations, allowing for each component to thrive. The freedom to thrive on all demographic and species levels needs to be the goal of environmental legislation, and the characteristics of ecology are the tools to help us get there, the tools to help us communicate, to unite, and to lay the foundation for change.