Dean Frederick Steiner, Photo: The University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design

Frederick “Fritz” Steiner is Dean and Paley Professor at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design, and co-executive director of the Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology. He served for 15 years as dean of the School of Architecture and Henry M. Rockwell Chair in Architecture at The University of Texas at Austin, having taught at Arizona State University, Washington State University, the University of Colorado at Denver, and Tsinghua University. Dean Steiner was a Fulbright-Hays scholar at Wageningen University and a Rome Prize Fellow at the American Academy in Rome. A fellow of both the American Society of Landscape Architects and the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture, he has written, edited, or co-edited 18 books, including Making Plans: How to Engage with Landscape, Design, and the Urban Environment (UT Press, 2018). Dean Steiner earned a Master of Community Planning and a B.S. in Design from the University of Cincinnati, and his Ph.D. and M.A. in city and regional planning and a Master of Regional Planning from Penn.

When you were a student at the University of Cincinnati, you were involved in the very first Earth Week in 1970. How did that experience shape your career?

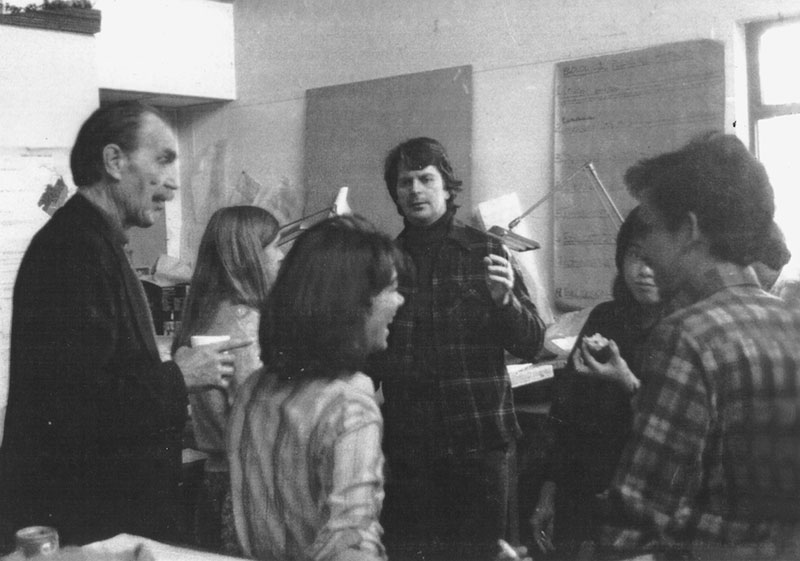

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was considerable activism on campuses concerning the war in Vietnam, civil rights, and the environment. The original Earth Week was a “teach in,” and it was meant to be an educational experience beyond the traditional classroom. I was co-chair of the event at Cincinnati, and one of my roles was to organize a book fair. In those days, there were relatively few books on the environment: Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring; books by Aldo Leopold, Barry Commoner, and Ralph Nader; and then there was Ian McHarg’s Design With Nature. I was a design major, so that book immediately appealed to me. I read the book and it changed my life. I decided that I wanted to learn what McHarg had laid out in Design With Nature, so when I finished my work at Cincinnati, I applied to the University of Pennsylvania and study with him. In the early 1980s, I returned to Penn to work on my PhD and I was invited to coordinate the LARP [Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning] 501 Studio, which taught landscape architects and regional planners how to read landscapes using the McHarg method. There, I worked with Ian McHarg, along with a cast of characters: a geologist, a soil scientist, an ecologist, a resource economist, and an ethnographer. It was a studio with around 70 students and six faculty from across disciplines.

Fritz Steiner (center) with Ian McHarg (left) and first-year landscape architecture students at the University of Pennsylvania, 1983. Photo:

For those who are unfamiliar with Ian McHarg, what can you tell us about his influence on urban planning and design, and on your career?

His contribution is well summarized by the title of his book, Design With Nature, and “with” is a very important word there. He developed a method for understanding landscapes and developing different options for development based on that knowledge. He used many techniques that had been developed by landscape architects and planners before him, such as map overlays and transects, but he brought in ecology as a way to overlay information and understand ecological relationships with transects. He advocated ecology as the fundamental science for landscape architecture and planning.

As a teacher, he taught both large lecture courses and studios. Both were seedbanks for his theories as was his practice. He founded a successful practice in Philadelphia which undertook projects around the world. On top of this, McHarg was a public intellectual who was frequently on television and speaking to large audiences. For me, McHarg became my role model as a teacher, writer, and reflective practitioner.

You have written so many publications, including The Living Landscape, which is described on one bookseller’s web site as “a manifesto…for architects, landscape architects, environmental planners, students, and others involved in creating human communities. If you had to recommend one of your books, papers, or chapters to our readers, what would it be and why?

I am currently working on a book, Design With Nature Now, with my colleagues Richard Weller, Karen M’Closkey, and Billy Fleming. The book, which celebrates the 50th anniversary of Design With Nature, is in press now and should be available in September. The book looks back at McHarg and his contributions, but its main emphasis is on what “design with nature” means now, in the Anthropocene. We discuss 25 projects at sites around the world that we that we think exemplify approaches to designing with nature now. Our aim wasn’t to just celebrate McHarg’s influence, so the book includes both descriptions and critiques of these projects. The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, our publisher, is very keen on the book having a broad audience because their major mission is to improve quality of life through land policy and land use.

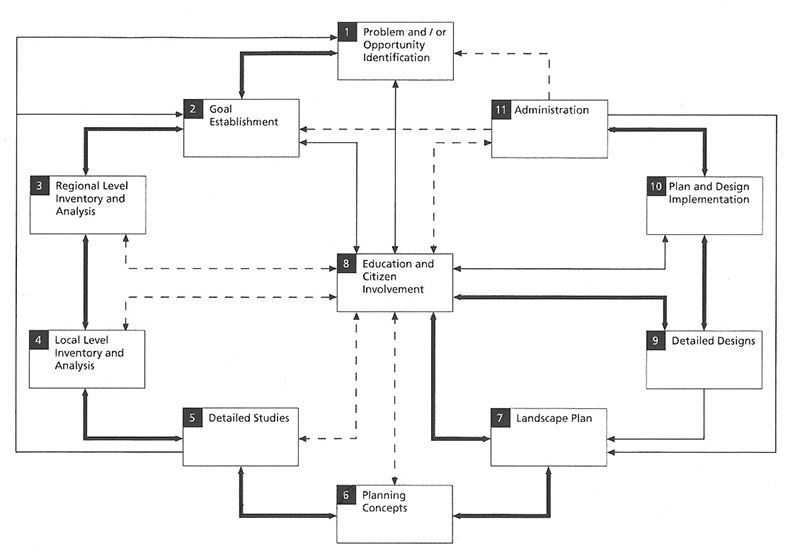

Ecological planning model from Fritz Steiner’s The Living Landscape: An Ecological Approach to Landscape Planning (Island Press, 2008)

What aspects of the city and urban site planning process are essential for urban ecology to be woven into the fabric of the city form?

It depends on the scale. Something planning and ecology have in common is that they both look at places through different scales. Urban design, community-scale, neighborhood, city, and regional plans all involve an inventory, assessment, or survey of the natural and cultural environments at some point very early on in the process. So that is one step where ecology can be very useful in understanding the area being studied. For example, when I was helping to create a new city plan for Austin, Texas, we needed to understand many dimensions of tree cover: the type and locations of trees, the relationship of trees and other vegetation to wildlife and songbirds, the role of tree cover in climate mitigation and human comfort. At the inventory stage of this city plan, understanding trees, along with other elements of the natural environment such as water, groundwater, soils, geology, and climate, was very important.

At other stages in local planning projects, the public is usually involved, and communicating ecological information and its value to urban residents is essential as well. Plans usually lead to either a built result or a policy result. If it’s a built result, and you’re redoing areas that include parks and open spaces, the role of ecology in the design of those spaces is very important. If the plan leads to regulations, it is important that they reflect the ecology of the area.

Where can our readers learn more about your work in Austin?

In the book Making Plans [How to Engage with Landscape, Design, and the Urban Environment (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018)], I describe the work we did for the City of Austin as well as the University of Texas campus. This book shows how ecology was used in both the campus and city plans.

What role can ecology play in addressing issues related to environmental and climate justice in the world’s urban places?

When we did the analysis of tree cover for Austin, we found that the western parts of the city, which are the whiter and more affluent, had more tree cover than the eastern part, which was poorer and had larger African American and Hispanic populations. There’s a social justice issue right there. The poorer people were living in areas with less tree cover, which was not only an aesthetic issue but a climate comfort issue. So part of the planning strategy became, “How do we increase green areas in poorer parts of the city?”

How might the understanding we’ve gained regarding equity and environmental justice have changed McHarg’s approach to reading the landscape?

McHarg was obsessed with health. In Design With Nature, he included a chapter titled “The City: Health and Pathology” in which he mapped places in Philadelphia where people were more likely to have physical disease, such as tuberculosis, heart disease, and diabetes; social disease, such as homicide, suicide, and drug addition; and mental disease. He then overlaid human factors, based on race and ethnicity. So he was looking at inequalities in urban areas back in the 1960s. What we have today is a deeper understanding of the causes of those injustices—things like redlining. We also have tools such as Geographic Information Systems to more accurately map and display those “pathologies.” I think that is extraordinarily relevant and important to understand.

The day that this issue goes live, the McHarg Center and the Department of Landscape Architecture at Penn’s Stuart Weitzman School of Design will host a conference called Design with Nature Now. Can you tell us about the McHarg Center and conference?

The idea of the conference, which is related to the book I mentioned earlier, is to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the book Design With Nature. It will look back at McHarg and his contributions, but it will also explore the relevance of Design With Nature today. The conference is also the official opening of the Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology. We will have a lot of terrific speakers at the conference—not only architects, landscape architects and planners, but also ecologists and humanists.

The conference coincides with three exhibitions funded by the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage. One exhibit presents the 25 projects we feature in the book Design With Nature Now. Another exhibit, Ian McHarg: The House We Live In, will focus on McHarg’s life and contributions. The third exhibit, called Laurel McSherry: A Book of Days, will feature the work of a landscape architect and visual artist. Laurel spent a Fulbright at the Glasgow School of Art and created art based on the Clyde River Valley in Scotland, where McHarg was born, as well as the Delaware River Valley, where he spent most of his life.

People are moving into cities now for many reasons, including fleeing conflict or the impacts of climate change. What role can ecology play in addressing and accommodating these vulnerable populations?

By making more cities more livable, we make them more livable for everybody. If we are creating cities with better water and air quality and more green space, that benefits existing residents as well as newcomers. The overall goal is to make the city a healthier and more pleasant place to live for all of us.

What about when it comes to ecology informing the policies that shape a city? What cities are leading the way there?

In the United States, Portland and Seattle are leaders in that regard, and tend to be ahead of the rest of us. They both have a high level of planning and design that is very conscious of the environment and social justice.

Earlier, you mentioned the importance of communicating the benefits of ecosystems in the planning process. One of those benefits is biodiversity. In your chapter in Ecological Wisdom, you write that the importance of biodiversity is recognized at the global level, but it “is not adequately considered in local planning and design decisions.” How can we do a better job conveying the importance of biodiversity to city planning decision-makers?

In a way, that is our life’s work.

Golden-cheeked warbler (Dendroica chrysoparia). Photo: Steve Maslowski from the National Digital Library of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service

For example, I’ll go back to Austin for a moment. Traditionally, with endangered species in the U.S., we’d look at a particular species and try to protect it. In the 1990s, Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt encouraged the habitat conservation approach, which is based on the simple reality that the most effective way to protect endangered species is to protect their habitat. Of course ecologists knew this, but policy makers didn’t. The City of Austin was a pioneer in applying that approach when they created the Balcones Canyonlands Preserve for the protection of [eight endangered species-two neotropical migratory songbirds and six karst invertebrates-and 27 species of concern.]

View of the Balcones Canyonlands National Wildlife Refuge. Photo: Matthew Rutledge

Another endangered species in Austin is the Austin Blind Salamander (Eurycea waterlooensis). The salamander’s only habitat happens to be in Barton Springs, which is the green, cultural hearth of Austin. In this case, it was fairly direct to make the relationship between protecting the springs for swimming and for the salamander. Figuring out how to connect species you’re trying to protect to the lives of everyday people is important and effective, but it’s a big job. One way to do that is through celebrating other species, as for example in Austin, the Mexican free-tail bats who inhabit the Congress Street Bridge and emerge, when they are in town, in great spectacle.

Washington Canal Park, one of the first parks certified under the Sustainable Sites Initiative © OLIN/Sahar Coston-Hardy

In the Ecological Wisdom chapter, I include examples of projects that were developed through the Sustainable Sites Initiative (SITES), which I helped develop along with the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center, the U.S. Botanic Garden, the American Society of Landscape Architects, and others. SITES, which is now managed by GBCI, is essentially LEED for the outdoors. In developing it, we used the ecosystems services concept as a way to organize a rating system. The SITES rating system is a great way to make biodiversity and other ecological concerns explicit to decision makers. It can help people understand the ecological tradeoffs for developing or changing a place.

In the afterword to the book Nature and Cities: The Ecological Imperative in Urban Design and Planning, you and your co-editors write that “ecological literacy… is an essential base for any design or plan to be relevant in today’s world.” How is ecology integrated into the graduate programs at Penn’s Stuart Weitzman School of Design?

It is most integrated into our Landscape Architecture program, but within City and Regional Planning and Architecture, there are components where ecology is central. In City and Regional Planning, there is an environmental planning concentration. We also offer an Ecological Planning certificate, and most of the people who do that program are Landscape Architecture or City and Regional Planning Students. We also have an Environmental Building Design section in Architecture, which focuses on environmentally appropriate building design, which is pretty fascinating as well. Ecology is very present in the graduate programs.

Studio review at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design. Photo: Stuart Weitzman School of Design

Can you tell us about any exciting projects related to ecology in urban planning in which your students or colleagues are currently involved?

Richard Weller, my fellow Co-Executive Director of the McHarg Center, looked at the relationship between biodiversity and urban growth and produced what he called the Atlas for the End of the World. Among other things, the Atlas shows where the most rapidly growing cities in the world are in relationship to biodiversity hotspots. As a follow up to that work, he has proposal for a world park to provide a global network of protected areas.

Other than Weller’s own follow-up with the park proposal, has the Atlas prompted any action/further studies by those outside of Penn, such as international organizations? National or local governments?

It’s hard to say exactly; the Atlas is essentially an audit of which parts of the world are meeting UN conservation targets and which areas are falling short. In that way it works to focus attention on certain regions. The Atlas has certainly been noticed by the conservation community—the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, non-governmental organizations such as The Nature Conservancy and the World Bank to name a few.

How can our readers stay up to date on that world park proposal?

The Landscape Architecture Department organized an elegant exhibit on World Park earlier this year, and it’s documented on our website. We publish a weekly email newsletter during the academic year, which is a good place to learn about projects like World Park.

Speaking of protected areas. Many of our readers may be involved or interested in large-scale conservation efforts. What is the best way to connect efforts to reintegrate ecology in urban areas to some of those more macro initiatives?

The sister discipline of urban ecology—landscape ecology—is helpful in understanding spatial phenomena such as corridor, mosaic, boundary, edge, and patch. The lessons from landscape ecology can be very helpful in connecting larger ecosystem protection efforts with urban areas. For instance, the pioneering landscape ecologist Richard Forman applied these concepts in a regional plan for Barcelona; I used them in plans for North Phoenix and Valladolid in Spain.

In the preface to Nature in Cities, you mention that the conference that resulted in the book’s creation drew a new generation of leading professionals and rising stars. Who do you consider to be some of the rising stars in the field of urban ecological planning?

- Chris Reed, the founding director of Stoss

- Nina-Marie Lister, founding director of PLANDFORM and director of Ryerson University’s Ecological Design Lab

- Kate Orff, founder of SCAPE

- The cool Dredgefest group: Sean Burkholder, Justine Holzman, Rob Holmes and others

- Nick Pevzner and Ellen Neises, here at Penn

- This is a little nepotistic, but my daughter, Halina Steiner, is a landscape architect who teaches at Ohio State. There is a cluster of young faculty at Ohio State that is doing great work.

Halina Steiner at The Ohio State University, 2019. Photo: Knowlton School of Architecture

I have seen you cite Pope Frances’ second cyclical, (Laudato Si) On Care for our Common Home, several times. Why is that?

McHarg grew up a Calvinist Presbyterian, and while he continued to be a religious man, he struggled with the Judeo-Christian ethic, especially Genesis, where humans go forth to “multiply” and subdue the planet. I find it amazing that now, the leader of one of the world’s largest and most important religions is laying out an argument that care of the planet is an ethical and moral issue.

You can’t be pessimistic and be a designer.

Fritz Steiner (center) and Laurie Olin (left), practice professor emeritus of landscape architecture, participate in a design review at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design

In your speech at the Stuart Weitzman School of Design’s 2017 commencement, you said, “This is a golden time for design,” and that “the very act of design is an optimistic activity.” At a time when there seems to be so much environmental doom and gloom, and so many challenges facing our cities, how do you stay so optimistic?

You can’t be pessimistic and be a designer. You have to believe in a better future and you have to believe that through design, things can be improved in some way. It is a very hopeful enterprise.