Bethanie: I’m going to ask each panelist to share a brief introduction. We’ve also asked the panelists to share the name of a restorationist who has been influential to them, who they respect, or who they believe has helped move the field forward.

Tein McDonald: I’ve worked for over four decades in restoration, mainly facilitating natural regeneration, in Australia. As well as on-the-ground practice, I am convening Australia’s Restoration Decade Alliance, a consortium of 16 peak Australian restoration organizations working to support and promote the goals of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration in Australia. A person I hugely admire in restoration is Tony Rinaudo. Tony helped African subsistence farmers turn around degradation and recover thousands of hectares of their lands for the benefit of nature and people. He did this by showing them how they could facilitate natural regeneration. He currently works for World Vision in Africa and Australia. However, we need to admire all people who are working to address the restoration challenge, regardless of their contribution. We have thousands of volunteer Landcare and BushCare groups here in Australia, and other countries have similar movements going on, but we need many thousands more. We need small actions for millions of people to address the environmental crisis globally.

Tein working to restore a local reserve. Photo courtesy of Tein McDonald

Keith Bowers: I reside in Charleston, South Carolina and I work throughout North America on a variety of ecosystems at a variety of scales. I’m the founding and active principal of Biohabitats, an applied ecology firm that focuses on ecological restoration, conservation planning, climate change adaptation, and environmental justice issues. We’ve been practicing ecological restoration, planning, design, and construction for the past 35 plus years. The person who put me on the path to ecological restoration is Dr. Edgar Garbisch, a mentor of mine. He abandoned his career in teaching chemistry and moved to the Eastern Shore of Maryland where he founded the nonprofit firm of Environmental Concern. He dedicated his life’s work to figuring out how to restore salt marshes throughout the Chesapeake Bay, and that was back in the 1970s when no one could even imagine such a thing. His pioneering research and work led to breakthroughs in wetland restoration, plant propagation, and management initiatives that are still being used today.

Stephen Packard: I started in 1977 as a volunteer, and organized the Volunteer Stewardship Network in Illinois. I subsequently worked as a professional with the Nature Conservancy, Audubon, and whoever else would have me until recently. One of the things I am most proud of is my work with Bill Jordan, Don Falk, and others to help organize the Society for Ecological Restoration. I should mention two people I thought would be educational for people to get to know. One is Bernie Buchholz, a volunteer steward at the Nachusa Grasslands. In the middle of a 20-year career in finance, he showed up one day to volunteer. They said, “You seem bright. You seem like you could be a hard worker. We could give you 50 acres (out of their 3,800) to restore,” and he’s been there ever since. He became a leading founder of the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands, which raised $210,000 for research grants and $2 million for stewardship endowments. He was also a founder of the Middle Rock Conservation Partners. The other is Erika Kojima, another volunteer who quickly decided [ecological restoration] was what she wanted to do. She was in her 50’s at the time, and she said to her daughter and husband, “I don’t want to work anymore. I want to do this full time. Would you support that?” They did, and she went to work. When she says full time, it’s often from dawn to dusk, pretty close to 365 days a year. She not only does the physical restoration, but she also recruits and trains hundreds of people on many sites and empowers them to be community builders.

Nachusa Grasslands

Bill Jordan: My connection with ecological restoration goes back to my taking a job at the University of Wisconsin Arboretum in 1977. The Arboretum was the site of pioneering attempts at ecological restoration back in the 1930s and 40s. My job there was public outreach, so I asked myself, “What story do we have to tell?” The answer was the restoration story, which at the time was not on the agenda, but I thought about it anyway. The Arboretum was apologetic about their collection of restored communities because they were “human constructs”, but I had a different perspective. This was partly because my father was a forester, and I grew up with the idea that a person could do good work in the woods, and partly because some close family friends, Florence and John Retzer, had undertaken a long-term retirement project to restoratively manage of 90 acres of land near Waukesha, Wisconsin. In 1981, Keith Wendt, the ranger at the Arboretum, launched the Journal Ecological Restoration. A few years later, we organized a symposium on restoration ecology, and at the end of the 1980s, I was one of the people involved in the creation of the Society for Ecological Restoration.

Bill Jordan at at the edge of Curtis Prairie, with the University of Wisconsin Arboretum’s McKay Center in the background. Image courtesy UW Arboretum

Carolina Murcia: I live in Cali, Colombia. I am an independent consultant and see myself as somebody who bridges science practice and policy with my work. Thinking about the topic of this webinar and the idea of where we’ve been, I’d like to talk about a few people who aren’t on many people’s radars because they lived a long time ago. One is Emperor Dom Pedro II from the Brazilian empire, who [concerned about deforestation] ordered the creation of what is now known as the Tijuca Forest [in Rio de Janeiro]. The Tijuca Forest is about 10 times the size of New York’s Central Park. It was done by foresters, and it did not try to replicate the native ecosystem in any way, but it was the first attempt to reintroduce irrigation using native species. About a century later, Ricardo Codorníu y Stárico, a Spanish forest engineer, reforested 5,000 hectors of native vegetation in southern Spain. He did this with five native species in a matter of 12 years. By 1917, the area was declared a national park.

Tijuca Forest

Bethanie: That was perfect Carolina, and a good reminder that even though the name restoration ecology is new, the practice is not. Karen, we’re going to give it to you to close up introductions.

Karen Holl: I am a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz in the United States where I study how to restore forests in Latin America and grassland and forest ecosystems in California. Recently, I’ve also been spending a lot of time trying to improve the ecological and social outcomes of the massive tree-planting campaigns. I’ve taught restoration ecology for 25 years, and recently wrote my Primer of Ecological Restoration, which is a six-inch summary of the field from my work and teaching. I work with various conservation organizations to implement my restoration research. As an academic who works in restoration, I really admire people who span the science-practice divide. One person who I think does that really well is my colleague Pedro Brancalion at the University of São Paulo who has worked a lot with Brazil’s Atlantic Forest parks, the timber industry, government agencies, and NGOs to develop and apply innovative methods to scale up restoration of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. On the flip side, I work with several practitioners in California and elsewhere who really work to apply science in their efforts, and I think that dialogue needs to go in both directions.

Bethanie: What is one of the greatest lessons you’ve learned about ecological restoration over the course of your career?

Carolina: I was working for a conservation organization, so restoration was not on the agenda, but I was interested in it. I started pushing the concept within this organization and within my guild. As I started interacting with people from all over the world and of different disciplines, I began to realize that the ecological component of restoration was small compared to how much work needs to be done with people. People are a large part of the restoration process, from generating degradation to helping resolve it by engaging in restoration and ensuring that restoration efforts are sustainable over time. When I teach ecological restoration, I like to tell my students that if the whole process of restoring an ecosystem was comparable to a 24 hour period of time, you would plant the first tree or plant around 11 PM, because you would have to do a lot of work with people upfront to understand their basic needs before you can start doing the restoration. Only then, when you get everyone engaged and really address those issues, can you be certain that those trees you plant at 11 PM are going to make it.

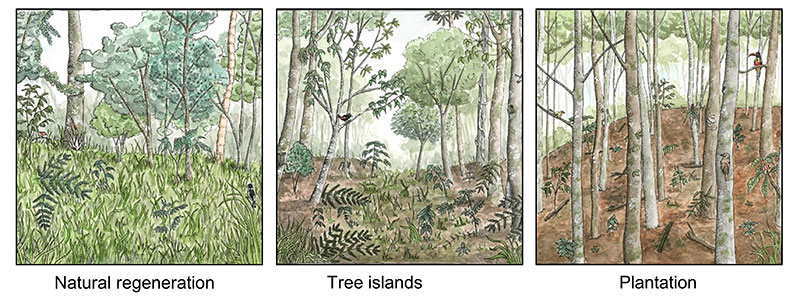

Karen: I completely agree with Carolina about the importance of including stakeholders. I’m not sure we’re planting the tree at 11 PM though, because I think that you might need about half the day to get ready, and then you need to plant the tree, and then you need to be following up with the stakeholders throughout. There is a lot of pre-restoration work, but there is a lot of post-restoration work, too. Another lesson I learned was that restoration strategies need to be tailored to the specific goals of the project and the socio-ecological systems, rather than being one size fits all. We can definitely learn from each other, and it’s important to share results to see what works in different situations, but results can vary. For example, I have a long-term project studying tropical forest restoration in Costa Rica. We replicated our project at 15 different sites in a relatively small area in Southern Costa Rica. We used the same three treatments at every site: we allowed the forest to recover naturally; we planted rows of native trees; and we planted patches of trees. We were looking at this idea of planting islands of trees that then would catalyze recovery and spread over time. There were certain things we could generalize, but we also found that the rate of recovery and the amount of biomass that we sequestered was an order of magnitude different across all these sites in the same area, and I’ve seen very different outcomes depending on the year and location.

Student illustration of plots in tropical forest restoration study in Costa Rica by Michelle Pastor

For those of you who are students, it is important to do experiments at multiple sites and to not draw general conclusions from individual projects. It is also important to compare and synthesize what works. Related to that… even though it seems like our method of planting tree islands (applied nucleation) makes sense ecologically and is similarly effective to planting more trees as a restoration strategy, from a social standpoint it may not always be as appropriate. A small land holder may want trees of certain species planted on their property. We must think about which results are generalizable and pick approaches that fit the ecology and the stakeholders involved.

Stephen: What I believe I’ve learned the most compellingly is the value of community and public support. A project we did at the Orland Grassland is an example. Owned by a local conservation agency, it was a thousand acres that had just been sitting there for decades. We organized a program to restore high quality prairie and oak savannah on that site. A wonderful leader, Pat Hayes, came in as a volunteer and took on the major responsibility of involving the community. She engaged high schools and neighbors and received great media coverage. In response to her work, we got a $12 million grant from the Army Corps of Engineers through the local congressman for restoration. $12 million dollars is nothing to sneeze at, and she has helped secure more grants since then that have made all the difference. In parallel, the county forest preserve district here once had no staff, department, or budget for ecosystem restoration. In response to volunteers and positive publicity, they now have a staff of 18 individuals providing restoration work, and they’ve increased their annual budget from zero to $5 million dollars.

Volunteers broadcasting seed at Orland Grassland. Photo by Jeanne Muehlner

A negative example is the Illinois Nature Preserves System, which was a world leader 60 years ago when it was formed. Over the years, as original volunteers drifted away it ended up being more a part of the bureaucracy. The number of preserves increased from less than a hundred to more than 600, but the budget did not increase, it fell. Staff were lost, and there was no director for five years. A group of wonderful people have since started Friends of Illinois Nature Preserves, and now that’s turning around, but it couldn’t have been turned around by the professionals alone. It really needed the community.

Tein: We were talking earlier about the balance between different scales of intervention. Very often we go into restoration with a similar mindset to the one that caused degradation in the first place. We see ourselves as the drivers of everything, whereas in fact, I think with a bit more or humility, we can be looking at the processes that occurred in our ecosystems and try and assist those. I think a method where we work with natural processes can be much more effective in many cases than going in heavy handed with an idea of imposing a complete ecosystem that we are rebuilding. At times that’s really important, but we need to look first and see whether there’s evidence of resilience onsite and build that resilience often for a lower cost and greater ecological outcome than going in and rebuilding.

Bethanie: One of the questions we have from the audience is “What is the best way to start in the field of restoration as a recent graduate?” If you’re just stepping in or you just graduated from school, how do you get started?

Karen: I get asked that a lot, and my biggest advice is network, network, network and get your hands dirty and volunteer. My students tend to volunteer, do internships, and get hired for part-time seasonal work, and then go on to more permanent jobs. Look for opportunities to meet people and let them see you working in the field. Going to local conferences, meeting people, and getting a sense of what is going on is really important. When people contact me for references for my students, it’s partly about the academic training, and there are certain skills that are really helpful, like plant identification and GIS and wetland delineation. But it is also about your work ethic, experience in the field, and ability to problem solve.

Karen with students at a grassland restoration site

Keith: I’ll chime in and say that first of all, as Karen advised, get your hands dirty. Go out, volunteer, join a restoration company that does restoration construction and learn what it’s like to implement a restoration project. That goes a long way in practice. Having a varied background, whether you get an undergraduate degree in science and a graduate degree in engineering or vice versa, that you can bring to a firm, organization, government agency is also critical.

Bethanie: A great example was the person you admired, Keith—Dr. Ed Garbish, who started as a chemist and then shifted to this field. We have so many SER members who started in a different field and are so passionate about this work that they’re like, “This is what I want to do. I don’t want to be an accountant anymore. I want to be in restoration.” What advice would you give to those who can’t afford to volunteer and do unpaid internships?

Keith: If you’re doing an internship, you should be paid. Maybe that’s a bit different than volunteering for a community group that’s out there on a weekend. There are plenty of organizations and private firms out there that have paid internship programs.

Biohabitats senior ecological engineer, Chris Streb (L) visits a stream restoration construction site with interns in 2018

Karen: If you’re working another type of job, even going out one day a week to volunteer and make connections can help. You must network. Take every opportunity you can for any additional training or conferences and reach out to meet other people. A lot of jobs in the restoration field occur through word of mouth. You need to get to know the people who are hiring, and the best thing way to do that is to get out there and talk to them.

Keith: I would also mention that restorationists need accountants, they need attorneys, they need all kinds of service providers. Maybe you’re not directly involved in the actual restoration activity, but if you’ve got those other skill sets, you can certainly support restoration.

Karen: Grant writers, too.

Carolina: There are a lot of resources online where people can educate themselves on restoration. Start with SER’s web page.

Bethanie: What do you think are some of the most important milestones in the evolution of ecological restoration and why?

Bill: I would describe it as the “discovery” of restoration. There’s a difference between stumbling onto something and realizing that what you’ve got that is something new. I remember reading a biography of Christopher Columbus years ago, and it hit him at some point after the first couple of voyages, that “Hey, that’s a new world!” Of course, there were millions of people living there, but for Europeans, it was something new. Restoration had been “invented” in a clear cut, recognizable way around the beginning of the 20th century but nobody made anything of it as a distinctive way of managing or relating to the landscape or an ecosystem. That took place during our careers and we, in various ways, contributed to that.

Karen: I agree that maybe we in the Western world discovered restoration a hundred years ago, but a lot of indigenous cultures were involved in restorative activities long before that, and it is important to acknowledge that.

Bill: Yes. For example, burning prairies was invented by Native Americans, of course. That’s a major example. That’s right at the front doorstep of restoration as we know it in North America.

Tein: I agree that the consciousness in our contemporary times of restoration—waking up to the need—was a big milestone. As far as the modern movement of ecologic restoration, the sharing of knowledge between practitioners has been a critical milestone, and I believe that this started with Bill’s initiative to start the journal Restoration and Management Notes [now known as Ecological Restoration]. That triggered a great deal of activity, and it wasn’t long afterwards that SER as an organization was born out of the interactions and collaboration of all those players. SER’s first conferences were also milestones that inspired many. For new people entering the industry, those conferences, and the exchanges through journals, newsletters, conferences, webinars, and seminars are very important. The milestones of ecological restoration have included improvements in education and training. Our curricula started to become more focused on the basic principles of ecological restoration, and that is continuously evolving. Technically and philosophically, I think the SER Primer was a big milestone, particularly it’s identification of the role of a reference ecosystem. Whether we’re rebuilding ecosystems from scratch or regenerating ecosystems, that concept of reference ecosystem is really important.

Bethanie: There are several questions from the audience related to climate change, and there is also a question about the incorporation of indigenous knowledge and partnering with indigenous communities in ecological restoration. Keith, you were next in the queue. In the context of milestones do you have any thoughts on those two issues?

Keith: I’ll answer both of those, I think, in a roundabout way here. Being in the practice for 35 plus years, (as many of us on this panel have), sometimes we don’t recognize that milestones are happening because it’s this continuum of work that we’re doing. It takes something like this discussion to sit back and think about that from an objective standpoint. From my participation in SER as a board member and chair for about 12 years, the idea of traditional ecological knowledge and the role that it can play in the practice of restoration hit me hard. Yes, certainly we need to be doing that. We need to be doing that more so today than ever, and that of dovetails right into the issue of climate change. How are ecosystems going to adapt over time as climate changes, nutrient exchanges change, and as our landscape is continuously modified? We need to think about adapting the practice of ecological restoration to that, and about how indigenous peoples managed the landscape, some of the techniques they used, and how they adapted those techniques to conditions. That is a very valuable tool that we need to have in our toolbox. From a private practice standpoint, we are always striving to incorporate those ideas into the projects, but because of time, budget, client preferences, and regulations, it becomes difficult. The more that we can initiate policies, best practices, and standard practices that incorporate both climate change adaptation and traditional ecological knowledge, the better off we’re going to be.

Bethanie: As somebody working in the field, I’d like to also add my input. I think another important milestone was when the field of restoration was named and we started talking about its definition. One milestone [was the recognition that ecological restoration] is not about going backwards. It’s about putting an ecosystem back on its natural trajectory and being clear that restoration is learning from history and then moving forward to try to assist nature with being in a functional condition.

Carolina: I want to refer to another milestone, but it is of a different scale: the Aichi Targets. Back in 2010, at the meeting of the Convention of Biological Diversity, one of the Aichi targets was to restore 15% of the degraded lands in each country. Even though we are very far from having achieved that, it actually put restoration in the political agenda. The global realization, at that political level, that restoration was important for stemming the loss of biodiversity and for addressing issues like climate change cannot be discounted.

Bill: Restoration, developed as a performing art, is a way of generating the values that underlie human behavior, and therefore, will determine to a large extent the future of life on this planet. Restoration is a way of doing that with respect to nature as a given, not something that we made. That’s half of the human experience. The other half is what we create and invent. So it’s important: nature as given.

Bethanie: Thanks Bill. Just to link together what you and Carolina said, you started to answer this question by saying that one of the milestones was when we discovered something that already existed. With Aichi Targets, and now the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, globally, we’re discovering that this tool is here. Even though it’s been here for millennia, it’s becoming discovered as something we really need to invest in. I’m going to move on the next question. What do you think can be accomplished in the UN Decade?

Tein: It’s a really big question, of course, because we’re very accomplished at making promises and setting targets that we never keep. The urgency is enormous, and we have to keep the momentum up. I think if we achieve nothing else, we must accomplish turning orders of magnitude more people onto the restoration mission. I understand that we’ve got to achieve the outcomes as well. There are groups that are dedicated to that, and they will continue to do it. If we can’t attract the hearts and minds of people—normal everyday people—and change our practices so that we reduce the processes of degradation as much as undertake restoration, we’re going to miss opportunities. We need to provide a hook of hope for broader action by individuals, organizations, and governments. Restoration provides this hook but making that link to people’s lives is going to be important.

Bushcare volunteers removing Lantana at Korinderie Ridge Bush Regeneration week, north coast NSW, Australia. Photo courtesy of Tein McDonald

Bill: The idea of developing a restoration as a performing art is crucial to that. When we talk about traditional people doing restorative work, it was very commonly centered on festival behavior—activities that pertain to the human experience of nature and the human responsibility for it. It wasn’t just applied science. After seeing a movie about [prairie restoration at the Wisconsin] Arboretum when he was in second grade, my son said, “It’s really pretty boring. You could cut out a lot of that stuff, but just keep the prairie fire.” That was his take when he was about eight years old. And there’s some wisdom in that.

A prairie burn. Image courtesy of UW Arboretum

Tein: My husband and I are going for a holiday in a couple of weeks, and the thing we want to go to is called the Festival of the Eels in Lake Bolac in Victoria, Australia. It is a festival combining a celebration of indigenous culture and the recovery of that culture and ecosystem. It pivots around the eel harvest and the management of the riverine environment. I totally agree, Bill. If there was more of this, I think we would raise a lot of interest. We can only continue to act as a steward for so long, and then we need a break from it. We need restoration to be nourishing in itself. Particularly now, when just to be able to afford a roof over your head, you’ve got to work well into your normal retirement years. And then you are looking after your grandchildren because your own children can’t afford a house unless they work forever. Voluntary work is difficult, but if it was more part of the culture and a nourishing personal activity, I think this is where we need to focus our attention.

Festival of the Eels ©John Tadigiri

Stephen: For me, the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration will depend on whether people care or not. I think we have a moral and professional responsibility to help foster people caring. I remember when we started doing this work everybody who came by would say, “What are you getting? What are you harvesting? What are you taking from nature?” It wasn’t long afterwards that those people came along and said, “Thank you for taking care of the ecosystem.” And it wasn’t long after that when President Carter put out an edict saying native species need to be used to restore highways. It was becoming part of the culture, at least in a small way. It seems to me that during the UN Decade, we must set inspiring goals and do inspiring projects and get them covered by David Attenborough– like programs. We need patriotism towards the planet.

“We need patriotism towards the planet…”

Keith: I agree that the cultural, spiritual, social aspects of ecological restoration should be front and center in the next 10 years. I would also add capitalism in there. There are a lot of problems with the way we have our economic structure now, and capitalism is one of the culprits, but I also think it can be a partial solution. We need to embed this into our economic system. I’m hopeful that through this next decade, we can demonstrate that ecological restoration can be a thriving, robust business that provides livelihoods for thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of people across the globe.

Bethanie: I want to summarize a some of the comments here, because there was a lot of discussion about performance and festival and caring. I want to bring in some of the words from Robin Wall Kimmerer, who was a keynote speaker at our conference in 2021. She talks a lot about “reciprocity.” Several terms that you all used just now, such as “patriotism toward the planet” and “nourishing” are about reciprocity and understanding that when we give to the planet, the planet gives back to us. When we consider what the UN Decade can accomplish, there is this idea of changing hearts and minds, that if we could create a culture of reciprocity towards the planet by 10 years from now, that would be extraordinary. Even if you start by building it in small pockets and then it grows—like Karen’s applied nucleation— I believe it gets to some of the points people are making. I would like for us to move onto the last question. What do you think are some of the issues that remain unresolved in the field of ecological restoration and specifically, which are the most important to address now? We’re going to start with Karen on this one.

Karen: I have three broad areas, a couple of which have been discussed. I think the biggest challenge is that we need to reduce the drivers of ecosystem destruction in the first place, which are overconsumption, population growth, and inequitable wealth distribution. We’re living on a finite planet and restoration can’t be viewed as a simple solution. I see a lot of this in these massive tree planting campaigns, where people want to plant their way out of climate change. Those of us who work in restoration know that we’re never going to totally be able to restore ecosystems, so first and foremost, we need to be preserving ecosystems. We must think about a radical change in our lifestyles. Second, we need practical solutions to scale up efforts. Small scale restoration certainly has its place, but if we’re going to meet the goals of the UN Decade, we must think about what’s going to be feasible ecologically, socially, and economically to scale up. That means not taking any approaches off the table and really thinking creatively. An example can be seen in some of the work I’ve been doing with Pedro Brancalion. He is looking at working with the timber industry in Brazil to interplant eucalyptus, an Australian species, with native species and then log out the eucalyptus to help fund restoration. As a Californian, I’ve seen the effects of eucalyptus and I thought, “Oh my gosh, why would you do that?” He’s trying to look at a funding model that would help scale up restoration. We must be creative and think about how we can meet the needs of people and ecosystems in a way that’s financially viable.

Karen ((L), Pedro (R), and graduate student Calle

The third thing we need is more accountability. As Tein said, we set these targets out there and then we don’t achieve them or sometimes we don’t know if we’re getting there because we aren’t monitoring. We have to be realistic. What are we aiming for? It is important for projects to have very clear objectives. We’re not going to achieve everything in every project. What are your objectives? When are you going to measure them? And if you don’t hit those objectives, what are you going to do to fix it and to adaptively manage? Right now, we’re throwing out numbers, and in most cases, we aren’t coming close to meeting them.

Stephen: I will boldly say that I think one of our challenges is to deal with incompetence and fraud in the field. I hear, again and again, horror stories from landowners who have hired restoration folks. Payment is often according to time and materials, not according to whether there’s success, and it’s often hard to write contracts that cover all the details. SER’s efforts towards certification are a step in the right direction, but it can’t be a rubber stamp kind of certification. It’s interesting to me that professional organizations for lawyers’ doctors, and architects see the need to discipline or withdraw certification from people that don’t deserve it. That sounds a little scary, but I think it’s something that our field has to think about.

Bethanie: Keith and I were actually talking about certification pretty recently. Keith, do you have any comments on that?

Keith: I agree. It’s interesting that an engineer needs a license to build a bridge, an architect needs a license to build a building, yet we’re tinkering with ecosystems that are infinitely more complex and arguably would have much more of an impact on our wellbeing and our children and grandchildren’s wellbeing. We have the certification program, which is great, but we’re behind on making sure that people that are practicing restoration on a large scale have the experience and knowledge to do so. I’m all for everybody going out and doing as much restoration as possible, but I think there needs to be a system in place where when we are dealing in large scale landscapes, large scale restoration projects, that there is rigor behind that.

Keith with students at the University of Pennsylvania’s Stuart Weitzman School of Design

Bill: Keith and Steve both mentioned the need for certification. I would say the strong parallel here is medicine because this is a form of medicine, really. It is a healing art.

Carolina: I would like to follow up on Karen’s list. Those are excellent points about gaining better knowledge of how to do restoration, but there is the other aspect of it: how do governments implement restoration at large scales? How do governments incorporate restoration into their plans? There is a major gap there between what we’re doing in the practice and science realm of restoration and the kind of information that governments, policy makers, and investors need to get in on the game. We need better quantification of costs. Not just how much it costs to do restoration, but what are the numbers on the benefits of restoration? It is important to put restoration into the language used by this sector of society. The other thing we need to provide are better definitions. What does it mean to have restored a site? We used to talk about a reference state or system, which in our minds was perfectly clear. But for somebody who doesn’t know what an ecosystem is, or understand the spatial and temporal variation of ecosystems, what does it mean that an ecosystem works?

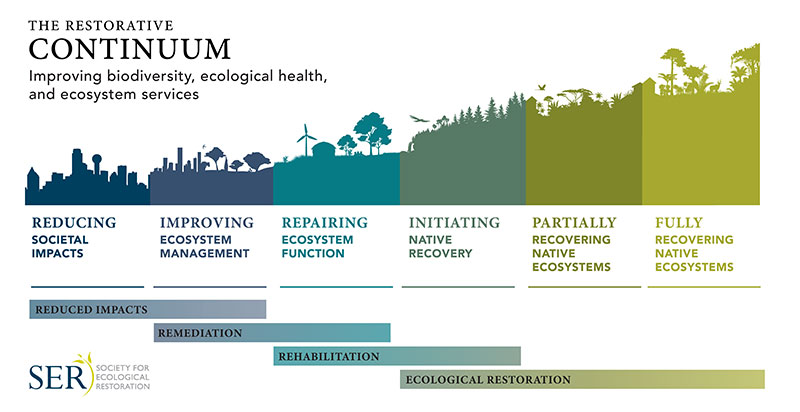

Bethanie: There’s a question on the table about the difference between ecosystem restoration and ecological restoration. SER defines ecological restoration as the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that’s been degraded, damaged, or destroyed. SER has introduced (thanks to Tein and many other colleagues) something called the “restorative continuum,” which articulates different restorative actions. The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration has defined ecosystem restoration as anything along the restorative continuum. In the restorative continuum, ecological restoration is reserved for those actions that really move into the native recovery space, and ecosystem restoration also includes things like agroecology, agroforestry, and efforts where you may be restoring some structure and function.

Karen: We can argue about language, but I think the most important thing is that each project have very clearly identified primary goals. There is always going to be some balance between human, ecological, and carbon sequestration needs so [it is important to be] clear about which is the priority, and then balancing those. A lot of times you have people just saying, “Okay, we’re going to do everything in every project,” and there are tradeoffs.

Bethanie: Here’s a question from the audience that I think gets at that: “What are some methods used to encourage more proactive, rather than reactive restoration? And I’m not sure what the person who wrote this meant, but I think of reactive restoration as mandatory restoration: you’re destroying something here, so you have to restore something there. How do we really encourage proactive restoration, where we’re moving the needle from a global phase of degradation to a global phase of restoration?

Bill: Make it a festival.

Tein: What occurs to me rather than method, is strategy. Many countries are working hard to identify strategies for conservation and restoration based on real need for populations of species. Often in other countries, like in Australia, we’ve undertaken planning for development, and it’s very difficult to retrofit outplanning for conservation, but it’s never too late. This is an imperative, I believe. Thank you.

Keith: 80 to 90% of our work is what we would consider proactive restoration, versus mitigation. I think it comes down to a recognition that we’ve got climate change and overconsumption, and we are depleting resources. Conservation should be practiced first and foremost, but that’s not enough. We all know that. We have to be restoring degraded lands and it needs to become embedded in policy, and it needs to be part of the GDP. What I hope to see in this Decade on Ecosystem Restoration is the recognition that this is not a luxury; it’s something that we need to do, and we all need to take a proactive approach.

Keith Bowers (R) collaborating with team members on a Land Management Plan for Sullivan’s Island, SC

Bill: I don’t want to sound like a broken record, but anthropologist Eugene Anderson has pointed out that anthropology knows of no society that has succeeded in achieving a sustainable relationship with its environment without ritualizing it. That’s the key to engaging people: turn it into a festival or some source of engagement. That’s value creation and that’s the key to the future. Some years ago, my wife pointed out a scene in A Midsummer Night’s Dream that we call the climate change scene. It’s in Act Two, Scene One. The queen of the fairies is arguing with the king of the fairies, and she accuses him of interfering with the rituals the fairies perform in order to maintain the order of nature, as a result of which the climate is failing. Take a look at this passage, it’s amazing. It’s 30 lines of gorgeous Shakespearean iambic pentameter, in which she describes climate change. I think it reflects what Gene Anderson points out in his observation about traditional, ecologically successful societies.

Bethanie: There is a lively discussion in the chat about the importance of K through 12 education and restoration, and I want to promote the idea that we need to be starting early and really engaging at all levels. There is also a question about scale. Does anybody have any comments on how we scale up?

Tein: I think scaling up is always going to be a tradeoff for quality. We need to be clear that certain functionalities may be traded. Biodiversity, persistence, and a lot of qualitative elements of ecosystems will be lost if we trade up, but we need to scale up to achieve things like carbon sequestration. In reality, I believe that if we want to achieve quality outcomes, we need to scale up the number of people involved and the number of projects, rather than the size of each individual project. Maintain the quality, scale up the effort.

Keith: I would also suggest that we have to be strategic in how we scale up. We must use the science of conservation biology and landscape ecology, and we must think about food webs, large carnivores, and wide-ranging species, and where will we have the most impact and effect. It may be very local things that we do, but those local things will scale up impact tremendously.

Carolina: Large scale restoration needs money, and that comes from private investors and governments. The UN Decade action plan for Latin America and the Caribbean has one major module on how to help countries develop their national restoration plans, and how to get governments to understand the importance of investing in restoration. The Convention on Biological Diversity is pushing an effort to train government officials on restoration. I think there is hope there, but I think that we also need society to give these governments a push.

Bethanie: I want to come back to the beginning where we asked that first question, and there was a commonality that we need people and science together. We need to involve communities in this process, and if we don’t, we’re not going to succeed. That was reemphasized by this concept of ritual and performance, and that’s one of the ways to involve people and create this space for people to care about restoration. We talked about the importance of scaling up this effort, and doing so with quality, but as Tein said, we also need to scale up the number of people involved and engage them in a nourishing, maybe ritualized way. Interestingly, we close with this question of science, and how to make sure that we’re incorporating the science and linking science and practice together in developing plans that are high quality, make sense, and financing implementation.

I cannot thank our panelists enough for the great insights and input that you’ve provided. And I will reiterate, there are many, many resources available, so follow up with Leaf Litter and Biohabitats, or follow up with SER if you have questions that weren’t answered, and we can try to get back to you on some of those questions. If you want to help scale quality and people and ritual altogether, please consider participating in Make a Difference Week in June.

NOTE: Although panelists were not able to address all of the questions received from participants during the 90-minute session, they were able to do so afterwards. We are happy to provide those questions and answers.

To view a video of the symposium, click on the image below.