Images (L-R) Opuntia stricta being cleared in communally managed rangeland in the Mukogodo area of Laikipia, Kenya; outplanting thermally tolerant coral stocks in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of O’ahu, Hawai’i. Photo by Shayle Matsuda; Tree seedlings being removed from Burns Bog located in southwest British Columbia, Canada. Photo by City of Delta

In the Demerara-Berbice river basins of Guyana, a university researcher evaluates plant colonization on former bauxite minelands. On the shore of Wisconsin’s Manitowoc River, a botanist gathers information needed for a grant application for a habitat restoration project. In Subang, West Java, an ecologist conducts a site inventory to inform an urban forest enhancement project. Though these individuals are worlds and oceans apart, they are united in their passion for protecting and restoring Earth’s ecosystems. They are also connected by something else: membership in an organization dedicated to advancing the science, practice, and policy behind this work–the Society for Ecological Restoration (SER).

SER formed just as ecological restoration was emerging as a discipline. While working as a biologist on environmental impact projects for the California Department of Transportation in the early 1980s, zoologist John Rieger sought to learn what others in the field knew about restoring ecosystems. To facilitate an exchange of information, he organized the First Revegetation Symposium in 1984. Three years later, another Revegetation Symposium was held, and it was during a keynote speech by William R. Jordan III, restoration ecology pioneer and the founding editor of what is now the journal Ecological Restoration, that the seeds for SER were sown. In the speech, Jordan expressed the need for a restoration organization. A few months later, a steering committee comprised of Rieger, Jordan, and practitioners John Stanley and Anne Sands was working to form just such an entity. By September of 1988, the Society for Ecological Restoration and Management (which later dropped “Management” from its name) was off and running. From that initial steering committee of four, SER has grown to become a global network of more than 4,000 ecological restoration scientists, practitioners, students, and businesses representing more than one hundred nations.

1992: SER Founders Bill Jordan, John Reiger, Anne Sands, and John Stanley. Image courtesy of SER

SER’s mission is to advance the science, practice, and policy of ecological restoration to sustain biodiversity, improve resilience in a changing climate, and re-establish an ecologically healthy relationship between nature and culture. A primary strategy in pursuing this mission has been the development of a diverse, connected, and committed community of SER members.

“A lot of people join SER because they want access to the most current information about ecological restoration,” said SER Executive Director, Bethanie Walder.

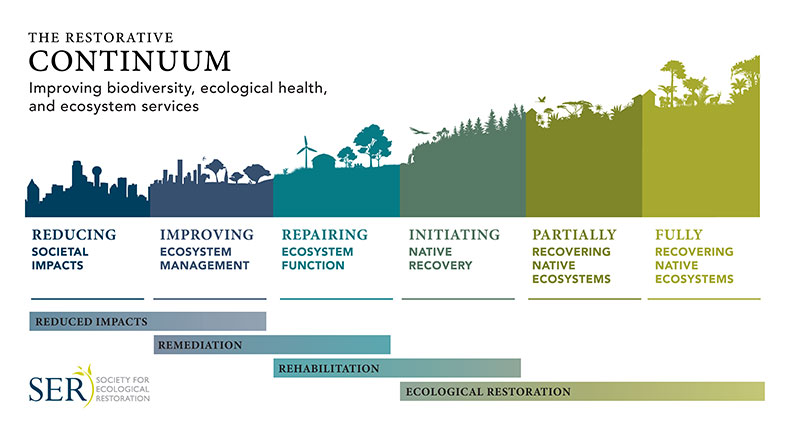

Indeed, SER members have abundant educational and networking resources at their fingertips. Publications range from periodicals to guidance documents, including the peer-reviewed journal Restoration Ecology, a 28-title book series on “The Science and Practice of Ecological Restoration” and the most downloaded document in Restoration Ecology’s history, International Principles and Standards for the Practice of Ecological Restoration. Intended as a blueprint for restoration that yields lasting environmental and social good, the International Standards organizes ecological restoration and related activities along a “Restorative Continuum” that allows practitioners to apply the most appropriate restorative approach for their specific ecological, social, and financial context. Updated in 2019, the document is available in five languages.

SER International Principles and Standards for the Practice of Ecological Restoration and its authors

SER’s Restoration Resource Center (RRC), a robust database full of relevant publications, presentations, and project information from around the world, is available to anyone. As with all of SER’s resources, this massive clearinghouse of information is helping to ensure that all knowledge–even that gained through project failure–is shared rather than shelved, and spread rather than siloed. SER makes it easy for anyone to submit information to the RRC.

SER also supports professional development by offering the world’s only certification program for ecological restoration practitioners. The Certified Ecological Restoration Practitioner program, which offers Professional and Professional-in-Training designations, has certified approximately one hundred people per year since it began in 2017.

An early SER meeting in 1991. Image courtesy of SER

The organization has an increasingly active Student and Emerging Professionals Committee that is increasing the delivery of professional development opportunities for young restorationists. SER maintains an active Jobs Board and directory of academic institutions with programs related to restoration ecology. SER helps cultivate the next generation of ecological restoration researchers and practitioners through more than two dozen university-based Student Associations. Last year, new student associations formed in Nigeria, England, and Costa Rica. Duke University started one just last month.

Colorado State University’s SER student chapter at work. Image courtesy of SER

According to Walder, another draw of SER membership is the desire to be part of the global restoration community. “Being able to connect with other restorationists working in the same types of ecosystems, either in your backyard, or on another continent, and with people who are developing and sharing innovations, is one of the biggest benefits that members enjoy,” said Walder. SER members have many opportunities to connect with one another and learn about developments in ecological restoration research, tools, techniques, and policies. The organization has continental and regional chapters, all of which host in-person (though recently limited due to COVID) and virtual events, including conferences. The organization’s largest and most popular conference is the biennial SER World Conference, and the next one is scheduled to take place in 2023 in Darwin, Australia on September 26-30.

2019 SER World Conference in Cape Town, South Africa. Image courtesy of SER

The SER World Conference brings researchers, practitioners, policymakers, artists, social scientists, consultants, and students together to share knowledge, discuss industry issues and trends, and learn about emerging tools, techniques, challenges, and strategies for ecological restoration around the world. The weeklong conference typically has a packed agenda, with keynote addresses, plenary panels, poster and video presentations, and themed, concurrent sessions featuring speakers from across the globe. In 2019, SER began making recordings of World Conference oral presentations available to members for free. Non-members can access keynote talks for free and can also purchase access to SER’s full conference library.

The conference has always included arts, including, most recently, a series of powerful videos following restoration examples across three global migratory flyways. SER World Conferences also feature activities outside of the venue, where participants can see restoration at work on field trips and participate in pre-conference “Make a Difference Day” local volunteer restoration projects.

“The best thing about any SER conference is the field trips, where you can go out and look at what people have put back together,” said Walder. “You see systems returning to life. You see fish coming back into streams. You can see with your own eyes what happens when we do restoration, and it is so inspiring and empowering.”

Walder (2nd from L) on an arid lands field trip in Jordan, 2018. Image courtesy of SER

Although the need to hold the 2021 World Conference virtually put a damper on in-person activities, SER made the most of the digitally delivered event. With no need to travel, the virtual format allowed for significantly increased access to potential delegates, including providing keynote and panel sessions in two different time zone blocks to accommodate delegates from both the eastern and western hemispheres. In addition, SER hosted more than 20 virtual field trips, where participants could virtually travel to all kinds of ecosystem restoration sites in six different continents. Rather than eschewing Make a Difference Day, SER reimagined it. They decided to host it for the entire week rather than one day, and they encouraged people all around the world to do volunteer restoration projects where they live. The decision paid off. During SER’s first “Make a Difference Week,” nearly 3,200 volunteers donated 20,000+ hours of work to implement more than 140 projects in 34 countries. The project spanned the restorative continuum as well as the globe, with tons of trash and invasive species removed, thousands of seeds collected and plants installed, and tens of thousands of native plants put into the ground.

Make a Difference Week was so successful that SER has decided to host it annually every June, to coincide with World Environment Day and the anniversary of the launch of the UN Decade. There is now a Make a Difference Week website where anyone can register or find restoration volunteer opportunities. The 2022 Make a Difference Week will be June 4-11, and Walder cannot wait.

Photo by Wilmar Diriá

“People are in despair over climate change and think they can’t do anything about it,” she said. “With Make a Difference week, we want to show that individuals can make a difference, that local action, collectively, has global impact.”

Like the World Conference, many of SER’s regular, in-person networking opportunities have shifted to virtual over the last two years due to COVID. But despite this reality, the organization’s membership has grown by double digit percentages. “People want to be part of this community,” said Walder.

People want to be part of this community…

Deeply valuing the diversity of that community and recognizing that not all people—even those from wealthy nations—can afford to join professional organizations, SER took bold action in the summer of 2020 and adopted a new “Membership for All” structure. They replaced a discounted, “Low Income” membership, an option previously available to those from developing nations, with an “Equity” membership that is available to anyone. Qualification for Equity membership is based on the honor system. SER did not stop there. Borrowing an approach from non-scientific community organizations such as the YMCA, SER also created an “Open Doors” membership, which is free to those who cannot afford the Equity rate. According to Walder, the more inclusive membership structure dramatically increased accessibility to SER and SER events, including the World Conference, as well as diversity within SER. Both are welcome changes.

“If we want people to care about restoration and have the resources to do it well, we’ve got to figure out how to make those resources available to them, no matter their ability to pay,” said Walder.

Membership for All brought new members from countries such as Bangladesh, Mauritius, and Haiti, which had never before been represented in SER. In the case of at least one new Open Doors member, it also helped advance SER’s operations. Frank Kanyamula was working for a humanitarian organization in Malawi when he joined SER through the Open Doors program. Not long afterward, he joined SER’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee and then became the Chair of one of its subcommittees. After SER had to swiftly shift gears to a virtual 2021 World Conference, Kanyamula was hired by SER to help with logistics and with the promotion of Make A Difference Week in Africa. Thanks to his efforts, Make A Difference Week projects in Africa increased from two to 45. Kanyamula was able to include this experience in his application to graduate school, and he is now pursuing a master’s degree in biodiversity informatics at Malawi University of Science and Technology.

In addition to supporting, developing, and expanding its community, SER also advances its mission through partnerships. Some partnerships build capacity and come in the form of instructional workshops and training programs. In 2019, for example, SER partnered with the Dr. Bhanuben Nanavati College of Architecture for Women (BCNA) in Pune, India to deliver an open course (registration is available to any interested party, not just students of the college) on designing and implementing restoration projects based on the SER Standards. BNCA is now offering the course a second time, with plans for expanding it across India next year.

SER also partners to implement ecological restoration in ways that advance all aspects of the organization’s mission. For example, SER is currently engaged in a five-year partnership with the Fort Belknap Indian Community (FBIC) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to restore native seeds and grasslands. Dr. Cristina Eisenberg, an Indigenous ecologist and SER Board member, leads the program, along with Tribal leaders and elders. The program not only involves the collection of native grassland seeds for use in restoration on tribal and BLM lands; it also supports the Tribe in its collection and preservation of Traditional Ecosystem Knowledge. Such knowledge is explicitly recognized and promoted in the SER Standards, alongside science- and project-derived knowledge. This recognition of the importance of utilizing a broad diversity of types of knowledge is not surprising for an organization whose members understand the impact of biodiversity on a functioning system.

Indigenous tree nursery at Tooro Botanical Gardens, Uganda. Photo courtesy of SER

One of SER’s most notable partnerships is happening on the world stage. SER was one of the first entities to become a Global Partner to the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. One of its earliest actions in that role was helping the UN establish a shared, global vision of ecosystem restoration. Collaborating with the IUCN’s Commission on Ecosystem Management and the Food and Agriculture Organization, SER co-hosted its third global forum on ecological restoration and developed the Principles for Ecosystem Restoration to guide the UN Decade. Dozens of other organizations participated in the global forum, and hundreds of restorationists from all over the world participated in global consultations to develop and finalize the principles, which now underpin delivery of the UN Decade. The UN Decade also explicitly defines ecosystem restoration as including all of the restorative activities that are part of the “Restorative Continuum,” which spans from reducing degradation to fully recovering native ecosystem and encompasses ecological restoration. SER is now working with the UN FAO and IUCN to develop Standards of Practice for the Decade, tiered to the recently released principles.

Recognizing that achievement of the transformative change envisioned in the UN Decade will benefit from universal standards for restoration effectiveness, something lacking among existing restoration databases; SER is also helping to establish shared indicators.

“We have to move the needle from net degradation to net improvement if we want to stop the planet from unraveling and deal with climate change,” she said. “Conservation alone cannot do that. We must have conservation plus restoration.”

As part of the Global Restoration Observatory, a group of more than 40 organizations throughout the world, SER co-led the development of a menu of 60 core and secondary shared indicators to help evaluate restoration effectiveness and outcomes. These include 17 headline indicators that are aligned with the UN Decade principles. The intent is to create some common information across restoration databases to allow for better analysis over the long-term. “The more of these shared indicators people use, the more opportunities we will have to track global restoration outcomes,” said Walder.

One of SER’s current global policy objectives pertains to forest restoration. Initiatives such as the Bonn Challenge, New York Declaration on Forests, or the new trillion trees types of challenges have prompted the planting of or commitment to the planting of millions of hectares of trees worldwide to help address climate change. “While these are important and beneficial programs,” said Walder, “in some instances biodiversity may take a backseat to carbon sequestration priorities and incentives.” This could include, for example, afforestation of intact landscapes that may not be appropriate for forests, or the planting of native or non-native monoculture plantations when biodiverse forests would provide broader and more holistic benefits. SER is a member of the Global Partnership on Forest and Landscape Restoration (GPFLR), with SER’s Board Vice Chair Jim Hallett also serving as Vice Chair of the Partnership. GPFLR members seek to improve outcomes from forest restoration for biodiversity and ecosystem services.

“As people talk about trees as the machines that will solve problems,” she said, “we have to talk about restoring native forests as biodiverse communities that will not only sequester carbon, but also provide clean water, create jobs, and generate cooling, fuel, and food for local communities.”

Despite this and other challenges of leading a global organization at the forefront of the climate and biodiversity crises, Walder loves her work. “To come to work every day and try to make more restoration happen, make the restoration that happens more effective, and bring more benefits to people and nature? I cannot imagine a better job in the world,” she said.

Bethanie Walder

She is also unwaveringly optimistic. “Restoration is proactive and solutions-based,” she said. “We can change the future. We have the technology. We have the knowledge. We have the skills. We just need the will as a global society to do this. That’s all.”

SER is working to ensure that ecological restoration is a fundamental component of conservation and sustainable development programs all over the world. As SER members collectively expand, share, and apply their knowledge of ecological restoration to projects, programs, and policy, they are bringing that vision to life.