Loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta)

It could be the gruesome thud of a boat striking a sea turtle, the horrifying image of a dead sea turtle washed ashore entangled in fishing gear, or the heartbreaking sight of a female strugglng to hoist her body over a mound of newly dredged sand, only to stop short of a safe nesting site, exhausted.

Sea turtles have existed for over 110 million years, and they are the most migratory creatures on Earth, so they know how to adapt to changing conditions. But in the short time we humans have been around, our actions have caused them to suffer severely.

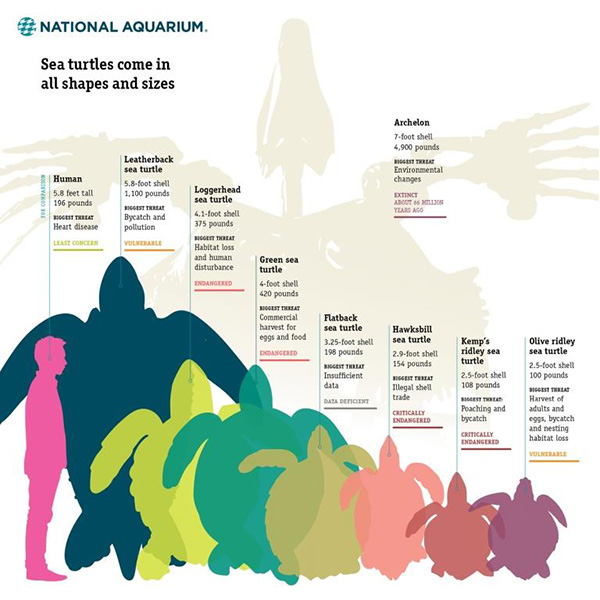

The longevity of these animal is just one of many things that make them such fascinating creatures. There are seven species of sea turtles in the world, ranging in size from the Kemps ridley, which typically measures around 24 inches long and weighs up to 100 pounds, to the massive leatherback, which can grow up to eight feet in length and weigh up to 2,000 pounds.

©National Aquarium

Sea turtles migrate hundreds or thousands of miles, following warm currents containing their food sources and often crossing or encircling entire oceans. The only exception is the flatback turtle, whose range is limited to the coastal waters of Australia and Papua New Guinea. Female sea turtles come ashore to lay their eggs. Some nest many times per season; some, like the olive ridley, may nest only twice each season. For most species, a single clutch contains 80–120 eggs. Once the female nests, she re-enters the water, leaving her eggs buried in the sand behind her as she resumes her migratory journey.

When the tiny hatchlings emerge from the nest one cool night in the future, they will—at great risk of predation—find their own way to the water. Males will never again return to land. Females, when reproductively ready, will find their way back to the very same beach on which they hatched to lay their own eggs. And so the cycle has continued since the time of the dinosaur.

Leatherback hatchlings (Dermochelys coriacea), Bocas del Toro, Panama

Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) eating sea grass

Even those unimpressed by the migratory journeys, navigation skills, or sheer longevity of sea turtles should appreciate the important roles sea turtles play in coastal and marine ecosystems. Primarily herbivorous adult green sea turtles eat so much sea grass they are sometimes referred to as “cows of the sea.” But this helps maintain healthy seagrass beds and recycle their nutrients. Sea turtles also help control sponge populations, which benefits coral reefs, and jellyfish populations, which, unchecked, can affect phytoplankton and zooplankton populations. In coming ashore to nest, sea turtles also provide enormous amounts of biomass and nutrients to beaches and dunes.

According to Defenders of Wildlife, a sea turtle hatchling begins life with a 1 in 1,000 chance of surviving to adulthood. Hungry crabs, birds, and other animals may pose the most immediate threat to an emerging hatchling, but predation soon takes a backseat to the many threats driven by us humans. If the lights from our coastal developments don’t disorient the hatchlings and they actually make it to the ocean, they will then face a lifetime of threats in the form of bycatch, poaching, pollution, direct take, habitat destruction, boat strikes, and climate change. All species face these threats, and all appear on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Some, like the hawksbill, Kemp’s ridley, and four populations of leatherback, are on the brink of extinction.

Hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata)

What is being done to protect sea turtles? How much do we really know about these long-lived, mysterious animals? What can we, as practitioners of ecological restoration, conservation, and regenerative design, do to better protect sea turtles and their habitats?

Roderic Mast with a leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea)

We begin by asking the experts. First, we chat with Roderic Mast, president of the Oceanic Society, co-chair of the IUCN Marine Turtle Specialist Group, and founder and chief edtor of the State of the World’s Sea Turtles (SWOT) Report.

Next, we speak with Joanna Alfaro, whose non-profit organization ProDelphinus works with artisanal fishing communities to reduce sea turtle bycatch off the coast of Peru.

We also hear from three NOAA Fisheries experts who are actively involved in the protection of sea turtles under the Endangered Species Act.

There may not be sea turtles in Baltimore Harbor, but there is plenty of sea turtle conservation happening there through the National Aquarium’s exhibits, outreach, and animal rescue efforts. We visit the National Aquarium and meet three sea turtles who may be doing as much for conservation as the people who care for them.

The National Aquarium's Amber White with a rescued green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas)

Jessica Norris reviews the book Voyage of the Turtle: In Pursuit of the Earth’s Last Dinosaur by award-winning author and marine conservationist, Carl Safina.

We shine Leaf Litter’s nonprofit spotlight on the oldest sea turtle conservation organization, the Sea Turtle Conservancy.

There are many ways you can help further sea turtle conservation. One is to volunteer to help local agencies find and protect sea turtle nests and eggs.

Turtle conservation volunteers in South Carolina

Find out what it is like to spend your early morning hours volunteering to help protect sea turtle nests and how important that donated time is to sea turtle conservation.

Grant Jones, founder of the firm Jones & Jones and recent recipient of the first-ever LAF Medal for distinguished work in applying the principles of sustainability to landscapes, shares some of his ocean-inspired poetry.

We encourage you to learn more about sea turtles by exploring our list of Resources.

We share some exciting news about the latest Biohabitats Projects, Places, and People.