The movement to revitalize post-industrial, urban waterfronts, which began in the 1970s, is in the midst of a promising new iteration. Recognizing the value coastal and riverine ecosystems add to urban communities, many cities are further enlivening their waterfronts by connecting more people to them, and enhancing the vibrancy of the water itself to improve and restore ecology. Urban shorelines are being re-imagined in ways that capture their potential to simultaneously stimulate economy, culture, ecology, resilience, and human connection to water. From the daylighted Sawmill River in Yonkers, NY, to the Hammarby Sjöstad eco-district in Stockholm…from Bangaroo Reserve in Sydney, Australia to the restored Buffalo Bayou that flows through Houston, TX…inspiring project examples abound. Here, we highlight four of the world’s many coastal and riverfront cities that have begun revitalizing–in the truest sense of the word—their waterfronts.

Seattle

For decades, Seattle’s central waterfront was dominated by two utilitarian structures: the two-mile long, elevated freeway known as the Alaskan Way Viaduct, and the 7,000-foot seawall along Elliott Bay. The seawall, which supported a portion of the Viaduct, had protected and provided level access to Seattle’s busy piers since it was constructed in the early 1900s. But for juvenile salmonids and other fish migrating from the mouth of the Duwamish River, whose habitat requirements include shallow, sunlit water and substrate for plant life, the seawall was not so beneficial. Its construction reportedly destroyed 68% of Seattle’s shoreline habitat and reduced salmon populations by 90%. Both the Viaduct and seawall were built when Seattle’s waterfront was highly industrialized and projects did not require environmental or design reviews, so it is not surprising that they were designed and built with little regard for coastal ecology and human connection to the waterfront.

But in the last decade, as the aging, degrading Viaduct and seawall were deemed seismically vulnerable after the Nisqually earthquake in 2001, and the city chose to remove and redesign them both, a unique opportunity emerged to reimagine Seattle’s waterfront as “A Waterfront for All,” and by all, the city does not just mean people. The new waterfront not only aims to reconnect Elliott Bay to the people of Seattle, but to the aquatic life that once benefitted from its nearshore ecosystem.

To achieve this vision, the City launched Waterfront Seattle, a multi- year program to rebuild Seattle’s waterfront following the removal of the Alaskan Way Viaduct. The program is led by the City of Seattle’s Office of the Waterfront, and it is being implemented in coordination with the expansion of the Seattle Aquarium and the development of the new, mixed-use Pike Place MarketFront.

Waterfront Promenade will run the length of the downtown waterfront

“The Waterfront Seattle Program is an example of putting Seattle’s reputation for sustainability and innovation into practice,” said Marshall Foster, Director of the Office of the Waterfront.

Beginning in 2010, the City engaged with thousands of residents, businesses and community organizations across Seattle and the region in plans for reshaping the waterfront.

“Community members and civic leaders identified a strong interest in supporting habitat, addressing stormwater, and creating opportunities to connect with the water,” said Foster. “In response, we solidified our commitment to ecological health and sustainable design as key components of the Program by integrating these commitments into the Program’s Guiding Principles.”

The Waterfront Seattle Program spans 26 city blocks and consists of numerous projects, including a rebuilt Elliott Bay Seawall, a new surface street providing access to and from downtown, a rebuilt pier with a floating dock, improved pedestrian connections between downtown and the waterfront, a dedicated bike lane, a public promenade with landscaping that manages stormwater and showcases native plantings, plus new parks, paths and access to Elliott Bay.

The rebuilt Pier 62/63 supports aquatic habitat by reducing overwater coverage. The project also features a new floating dock, allowing the public direct access to the water

The ecological showpiece of Seattle’s new waterfront is the new Elliott Bay Seawall Project. Managed by the Office of the Waterfront and Seattle’s Department of Transportation and currently under construction, the new seawall will not only protect the waterfront and serve as the foundation for its future, but restore the function of a natural shoreline. Its design (by Parsons) includes several innovative habitat enhancement features.

Unlike most seawall surfaces, which are smooth, the surface of the new wall is cobbled and includes shelves to promote the growth of vegetation and marine invertebrates. In-water, intertidal habitat benches provide shallow water habitat with spaces for aquatic life to hide and forage. The benches also help create a continuous shallow water corridor for juvenile salmon to travel safely along the waterfront.

Textured face panels on the seawall promote growth of vegetation and marine invertebrates

The new seawall cantilevered sidewalk with light penetrating surface panels

The corridors are sunlit, thanks to habitat-friendly sidewalks above, which are built with glass blocks that allow light to pass through to the water below. Native riparian vegetation will be planted along the seawall and at a new, intertidal beach to further enhance habitat.

The corridors are sunlit, thanks to habitat-friendly sidewalks above, which are built with glass blocks that allow light to pass through to the water below. Native riparian vegetation will be planted along the seawall and at a new, intertidal beach to further enhance habitat.

The corridors are sunlit, thanks to habitat-friendly sidewalks above, which are built with glass blocks that allow light to pass through to the water below. Native riparian vegetation will be planted along the seawall and at a new, intertidal beach to further enhance habitat.

Marine mattresses and the new textured seawall face south of Colman Dock

Light passes through glass blocks in the new sidewalk to the habitat below

“Ecological enhancement is woven throughout Waterfront Seattle Program improvements,” said Foster. So, too, is public access. A telling example is the rebuild of Pier 62, one of the first projects to be completed. The new pier, which will replace the older, toxic creosote deck and pilings with more ecologically friendly materials, will reduce net overwater coverage, benefitting aquatic life. It will also include a floating dock that will allow people direct access to the water and provide a space for cultural events for the area’s Coast Salish Tribes.

The Waterfront Seattle Program also increases greenspace within the urban core by creating 20 acres of new public space, adding over 800 new street trees, and integrating native vegetation throughout. According to Foster, the expanded greenspace and habitat will become an important addition to the regional parks system and provide ancillary benefits such as reducing urban heat island effect, supporting mental and physical health, and managing 6.6 million gallons of stormwater annually through green infrastructure.

Despite the hassles that can accompany major downtown construction projects (and in Seattle’s case, deconstruction as well) the public remains supportive of and excited about its new waterfront, according to Marshall.

“Seattleites are proud of our city’s natural beauty and our community’s strong commitment to environmental stewardship,” he said. “People are excited to be able to walk or bike directly to the waterfront, to interact with the water, to have new public green space to gather and enjoy views, to reduce the traffic noise pollution on the water, and to have additional greenspace and infrastructure that not only supports human recreation, but supports the habitat.”

The transformation is inspiring those working on it as well, as evidenced by this anecdote share by Marshall:

“Bardow Lewis, the Vice-Chair of the Suquamish Tribal Council and long-time fisherman and advocate for Salmon habitat in Elliott Bay, recently shared photos with me of young chum Salmon running along the new seawall. He shared his surprise at spotting them on a rare sunny day along the waterfront, and said he had never seen the likes of it. That was great to hear that from the Suquamish, who have been working for decades to improve conditions for the Salmon. We’re glad there are moments like these where you can spot a glimpse of the young Salmon swimming in the heart of a dense city like Seattle.”

A juvenile salmon makes its way up the improved salmon migration corridor

Toronto

In 1999, as part of Toronto’s bid to host the 2008 Summer Olympics, former Toronto Mayor Mel Lastman unveiled a new vision for the city’s 46-kilometer waterfront on the shore of Lake Ontario.

Included in this vision of a “necklace of green, with pearls of activity” was the theme of “Environment and Sustainability.” Stated within Lastman’s introduction to the vision was the intention to “restore thousands of acres of wetlands, green corridors, park, forest, and wildlife,” and to improve beaches and water quality.

Though the 2008 Games of the XXIX Olympiad would ultimately go to Beijing, the Government of Canada, the Province of Ontario and the City of Toronto recognized the potential of the envisioned, revitalized waterfront and made a commitment to bring it to life. Waterfront Toronto (formally the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation), an entity created by the three orders of governments, was charged with transforming nearly 2,000 acres of underutilized brownfield lands into a thriving downtown waterfront complete with businesses, attractions, leading-edge sustainable communities, and nearly 750 acres of parks and public spaces.

Toronto's transformed waterfront. Photo by Nicola Betts

Designated Waterfront Area with boundaries

The 30-year transformation is well underway, and in many ways, it is creating a more lively and livable waterfront for fish and wildlife as well as people. The effort is guided not only by a Sustainability Framework, but by an Aquatic Habitat Restoration Strategy which aims to ensure that opportunities for ecological enhancement are incorporated into all waterfront projects. The Aquatic Habitat Restoration Strategy was developed by Aquatic Habitat Toronto, an organization created to facilitate and streamline the many levels of design review that would be required by the three governments and the many parties involved. Waterfront Toronto is one of the founding members of Aquatic Habitat Toronto, a consensus based partnership between agencies including Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ministry of Natural Resources, and Toronto and Region Conservation (TRCA) in consultation with the City of Toronto.

By the end of 2015, with revitalization projects underway or completed along four of the waterfront’s five main precincts, nearly 109,000 square meters of aquatic habitat had been created. This was done in several ways, and often through projects done in collaboration with the TRCA, which works to protect and restore the health of not only the downtown Lake Ontario waterfront, but of the nine watersheds that form the Toronto region, and the Lake Ontario waterfront along its southern boundary.

Simcoe WaveDeck

A significant portion of that newly created habitat was associated with the central waterfront’s new WaveDecks, undulating wooden decks that project out over three (soon to be four) slips, bringing people beyond the water’s edge. Beneath these decks, nearly 1800 square meters of high quality, diverse fish habitat were created through the installation of root balls, large logs, and other material that provides shelter, spawning, and foraging opportunities for various species. This restored aquatic habitat is one of the primary reasons why, according to monitoring conducted by the TRCA, the number of fish species caught in Toronto’s inner harbor increased from only five in 2001 to 27 in 2013.

Pedestrian bridge across embayment at Mimico Park

Habitat enhancements have also occurred in association with the creation of the waterfront’s many new parks. Construction of the new Mimico Waterfront Park, for example, included the restoration of shoreline and wetland habitat along 1100 meters of previously inaccessible waterfront. A series of backwater lagoons and mixed sized aggregate piles provide shoreline protection as well as spawning and nursery habitat for sunfish and bass. Another place where people gained new access to the waterfront while fish and wildlife gained habitat is Port Union Waterfront Park, a 33-acre park featuring a 2.5-mile trail system that connects to that of Toronto’s northeastern neighbor, Pickering. That stretch of shoreline now has ten new cobblestone beaches, completed with improved aquatic and terrestrial habitats, and wetland features.

Nearly 75 acres of wetland are being created at Tommy Thompson Park, a man-made spit that continues to be a site for the disposal of dredged material from the Outer Harbour and surplus fill from development sites within Toronto, which extends five kilometers into Lake Ontario.

Now a stopover for migratory shorebirds, the park features seasonally flooded pools, mudflats and meadow communities for enhanced terrestrial habitat for nesting waterfowl, songbirds, small mammals, and butterflies. Hundreds of meters of aquatic habitat have been restored along the shorelines of the Toronto Islands and the West Shore of Toronto’s Outer Harbor to provide critical foraging, refuge, and overwintering habitat for northern pike (Esox lucius) and other species.

Tommy Thompson Park

Monitoring of the fish in Toronto’s inner harbor, which is primarily led by the TRCA, is helping to measure the success of completed habitat projects, and informing the design of future projects. For example, the TRCA has partnered with researchers from Carleton University to use Acoustic Telemetry to monitor the behavior and movements of eight different species of fish in the inner harbor. This information helps the researchers determine how and if the different species are using the various restored habitats along the waterfront.

In addition to habitat enhancement, water quality improvement is an important objective for a city located in one of 43 polluted Areas of Concern in the Great Lakes Basin. In addition to the impacts of industrial contamination and the loss of natural shorelines and wetlands, Toronto’s inner harbor has suffered from stormwater pollution and overflows from the combined sewer systems that remain in older parts of the city.

Stormwater management has been cleverly and beautifully integrated into many waterfront improvement projects. Even city trees are designed and planted with stormwater management in mind. At Sherbourne Common, a park that spans two blocks of lakefront, visitors not only enjoy amenities like a skating rink that doubles as a splash pad in the summer, but also a spectacular, water-themed sculptural display that rises nine meters from the ground, glows in blue light at night, and includes a 240-meter channel that flows along the park’s entire eastern edge.

Sherbourne Common North Photo by Nicola Betts

What makes the sculpture even more impressive is the fact that it is part of a system that is treating stormwater. The engaging installation, created by public artist Jill Anholt, showcases the journey of water as is it purified and returned to Lake Ontario. Stormwater captured and disinfected below-ground by UV treatment facility located beneath the park’s pavilion then travels underground where it is then released through the “Light Showers” and filtered through a biofiltration bed in the channel and flows out to Lake Ontario. Not far from the sculpture, a beautiful double allee of maple trees planted in silva cells line the waterfront promenade, enhancing tree canopy while further improving stormwater management.

Corktown Common, (designed by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates), located in the West Don Lands precinct, was once a brownfield site highly vulnerable to flooding. Today it is a stunning, 18-acre park that integrates stormwater management with flood protection, recreation, and the enhancement of biodiversity and habitat. Built atop a flood protection landform, the park includes a marsh that not only offers visitors the chance to view and enjoy wildlife, but receives and treats runoff from the western side of the park.

Corktown Common Marsh

In addition to the marsh, Corktown Common also includes edge woodlands and upland and lowland prairie habitat. Trails connect the natural areas with playgrounds, athletic fields, flexible, multi-season outdoor space, water play area, and other park amenities. “If you want a great example of a space where families thrive in a natural, urban environment,” said Barter, “Corktown Common is as good as it gets,” said Barter. All the while, the park provides services of flood protection for hundreds of acres of downtown Toronto.

According to Aaron Barter, Innovation and Sustainability Manager for Waterfront Toronto, the city is about half way through its journey toward the realization of former Mayor Lastman’s vision for the new waterfront. While there is much to celebrate in looking back at all that has been accomplished, Barter finds the next phase of the project, the transformation of Toronto’s eastern waterfront, even more exciting.

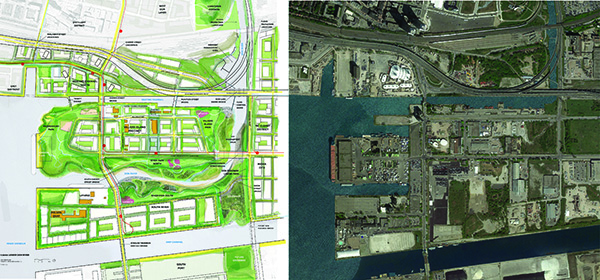

Once a 1,200-acre marsh on the Don River delta and one of the largest wetlands in Eastern Canada, this area became heavily industrialized in the 19th century. In the early 20th century, the marsh was filled and the mouth of the Don River straightened to facilitate industrial growth that continued until the 1970s and left behind a legacy of contamination. Today, plans are underway to “re-naturalize” the mouth of the Don River and transform more than 800 acres of neglected, underutilized, post-industrial waterfront into thriving urban communities that model the leading edge of sustainability. This massive revitalization project aims to simultaneously address the city’s need for affordable housing, economic development, flood protection, improved public access to the lake and river, and cleanup and environmental enhancement of contaminated land. The re-naturalization of the Don Mouth will take seven years to complete.

A major component of the revitalization of the eastern waterfront is the development of Quayside, the first new community planned for the eastern waterfront. Envisioned as a carbon-positive, inclusive and diverse community, Quayside will be “test bed for technologies and models that could be carried into the remainder of the eastern waterfront, including the Port Lands,” according to Barter.

Waterfront Toronto is eager to begin the Quayside project and will soon announce its selected Funding and Innovation Partner.

Toronto is having a moment now

Toronto's eastern waterfront, existing conditions (R) and renderings (L)

One project that will enhance access and ecology along the eastern waterfront is already underway: a $65 million initiative to fill in a large portion of lake around the northwest corner of Essroc Quay. The newly created landmass, which will begin construction later this year or in early 2018, will stabilize the area’s shoreline, as it is currently at risk of collapsing under flooding conditions. It will also add public waterfront space and increased aquatic and terrestrial habitat.

Since the revitalization of Toronto’s waterfront began, the increasing number and people – and fish – coming to its shoreline suggest that it is indeed becoming a more vibrant place, both in the water and at its edge

“Toronto is having a moment now,” said Barter. “The waterfront is right on Toronto’s doorstep, and it is a big part of reimagining what Toronto can be in the 21st century.”

Baltimore

One of the first American cities to re-imagine its waterfront back in the 1970s and 80s, Baltimore transformed its neglected, industrial Inner Harbor into a world-class destination, complete with a festival marketplace, shoreline promenade, science center, and National Aquarium. Yet despite the Inner Harbor’s revitalization, its history as a heavily industrialized port had taken an ecological toll on its shoreline and water. That legacy, combined with intense development in the watershed and aging stormwater and sewer infrastructure, resulted in polluted Harbor water that was all too often associated with fish kills, algal blooms, and floating trash.

Today, Baltimore is once again setting trends in waterfront revitalization. This time, the city is aiming to transform the water itself. Leading the way are two organizations with close ties to the water: the Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore, a non-profit collaboration of waterfront businesses, residents, and organizations, and the National Aquarium, whose campus occupies two piers in the heart of the Inner Harbor.

Five years ago, the Waterfront Partnership released the Healthy Harbor Plan, an ambitious initiative to make the Baltimore Harbor safe for swimming and fishing by 2020. The plan identified three main issues that needed tackling: trash, sewage, and stormwater. Included in the plan was the commitment to issue an annual “Healthy Harbor Report Card” to monitor progress.

The projects, programs, and relationships that have come out of the Healthy Harbor Plan are not only educating more people about the health of the Harbor water and how their daily actions impact it, but engaging them in doing something about it.

Because much of the trash and pollution that ends up in the Inner Harbor comes from city storm drains, the Partnership does not limit its efforts to just the water’s edge. Through their Alley Makeover program, for example, they work with upland neighborhoods to clean up alleyways, enhance community pride, and help raise awareness of people’s connection to the Inner Harbor. Partnership member Blue Water Baltimore, a watershed organization dedicated to improving Baltimore’s rivers, streams, and harbor and co-producer of the annual Healthy Harbor Report Card, also works to strengthen upstream communities while reducing their impact on the Inner Harbor. They do this by working with communities to plant trees, create rain gardens, remove impervious surfaces, clean up neighborhoods and streams, and educate people about their connection to the Inner Harbor.

Closer to the water, on one of the Inner Harbor’s five attraction-filled piers, is the Partnership’s privately funded Pierce’s Park (designed by landscape architecture firm Mahan Rykiel Associates), a one-acre public green space that iterates nature play, environmental education, and stormwater management. While visitors admire custom sculpture and children run through a tunnel made of live willows, bioswales and native raingardens capture and treat stormwater and provide pollinator habitat.

Bioretention = beauty at Pierce's Park

At the water’s edge, it is clear to see that very little of the Inner Harbor’s natural shoreline remains. But that hasn’t stopped the Partnership from initiating several pilot projects which not only test restoration techniques, but educate thousands of passersby along the Harbor’s highly visible waterfront.

Tidal wetlands that once lined Baltimore’s shores provided ecosystem services like cleansing polluted water, providing aquatic and terrestrial habitat, and buffering the land from storm surges. In 2010, the Partnership began testing a floating wetland prototype (designed by Biohabitats) which used discarded plastic bottles removed from the Harbor for flotation.

Floating wetlands in Baltimore's Inner Harbor

Volunteers from waterfront businesses and students from the nearby Living Classrooms Foundation Crossroads School have helped construct and plant the wetlands. Although the original design has undergone modifications and improvements, floating wetlands remain in front of Baltimore’s World Trade Center as a prominent feature along the waterfront. At their scale, the floating wetlands are not expected to have a dramatic impact on water quality, but they have proven highly effective at providing habitat-above and below the surface of the water-and capturing the attention of visitors to the Inner Harbor.

About a mile east of the World Trade Center, a new iteration of Biohabitats’ floating wetland design, which uses aluminum pontoons fabricated by Clearwater Mills for flotation, has been deployed along a pier that is now home to one of the Waterfront Partnership’s primary private sector supporters, Brown Advisory.

That same pier is home to an “oyster garden,” where volunteers in the WPB and Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s Greater Baltimore Oyster Partnership build and install cages in which they grow baby oysters as part of a restoration effort. Baltimore Harbor was once full of oysters.

It is in the water where the Waterfront Partnership’s efforts have garnered the most attention and excitement. Though the Partnership, Baltimore’s Public Works Department, and non-profits like Blue Water Baltimore work hard to prevent trash from entering Baltimore storm drains in the first place, it still flows into the Inner Harbor. Over the last three years, however, 543 tons of that trash was stopped dead in its tracks and removed from the Inner Harbor by a device known as “Mr. Trash Wheel.”

A water and solar powered trash interceptor designed by Clearwater Mills, Mr. Trash Wheel uses the current of the mouth of the Jones Falls to power a wheel which lifts garbage out of the water and onto a conveyor belt that deposits it onto an adjacent dumpster barge. In addition to things like discarded cigarette butts, plastic bottles, and Styrofoam containers, Mr. Trash Wheel has captured imaginations. With over 11,000 Twitter followers, and a recent mention on the popular TV game show “Who Wants to be a Millionaire?” Mr. Trash Wheel has undeniably entered popular culture. With large googly eyes affixed to its canopied covering, and a witty personality expressed through social media, the trash interceptor has become a brand.

“There are too many ocean cleanup projects that exist only as fancy computer renderings,” said Adam Lindquist, Director of the Healthy Harbor Initiative. “Mr. Trash Wheel is real and every day he proves his worth by picking up thousands of pounds of trash and debris before it can reach the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. Plus, he’s adorable and hilarious – which is more than you can say for most trash interceptors.”

The awareness and success of Mr. Trash Wheel helped fuel the funding of a second trash wheel, dubbed “Professor Trash Wheel” in a public naming contest, which was deployed along the waterfront late last year near the mouth of Harris Creek.

There is a vulnerability associated with implementing highly visible pilot projects like Mr. Trash Wheel and floating wetlands, but when it comes to improving water quality, the Partnership is willing to take risks.

“When we set a goal of making the Baltimore Harbor swimmable and fishable in just ten years we knew we would have to get creative and take risks, because the status quo was never going to get it done,” said Lindquist. “Cleaning up an urban waterway like Baltimore is something that few cities have accomplished, so there is no step-by-step guide for doing it. We need to keep inventing and innovating as we go.”

A key Partnership funder and collaborator that has been a driving force in the demonstration of innovative waterfront ecological enhancement techniques is the National Aquarium. The 36-year-old Aquarium, which helped spark the initial revitalization of the Inner Harbor, is once again a key player in its transformation. “We were here first to help placemaking,” said Kris Hoellen, the Aquarium’s Senior Vice President and Chief Conservation Officer. “We want to extend that to include the environment.”

For that reason, the Aquarium launched a bold initiative to transform its campus into a vehicle for connecting people to the waterfront in innovative ways, while modeling best practices in urban waterfront development in the face of sea level rise.

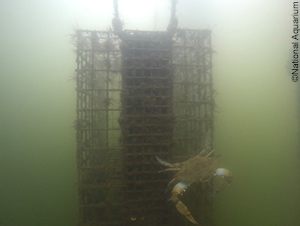

The Aquarium’s existing campus already includes features that showcase Maryland’s terrestrial ecosystems and demonstrate waterfront restoration strategies such as a floating wetland island (designed by Floating Wetland Solutions), and underwater habitat enhancement devices called Biohuts (designed by the French firm Ecocean).

Exploring the National Aquarium's Waterfront Park

Children watch a National Aquarium scientist monitor life in the Biohuts

The new campus takes ecological enhancement and education to a whole new level. Envisioned as a dynamic landscape and a living lab for ecological restoration, the new campus will include an urban wetland that fills much of the slip between the two piers on which the Aquarium sits, aeration diffusers to add oxygen to the water, submerged aquatic vegetation, terraced shelves that bring people closer to the water, and demonstrations of native landscapes along with interpretive signage explaining how they contribute to clean water.

The transformation of the Aquarium’s campus is scheduled to be completed by 2020. In the meantime, the campus’ existing habitat features continue to capture the attention of visitors and passersby. They also seem to have caught the attention of wildlife.

“We have a floating wetland prototype out there now and I often see people looking or pointing at it because there is an animal on it,” said Hoellen. “When people stop and look, a connection to the water is starting.”

“The Baltimore Harbor is far more rich with aquatic wildlife than we ever thought,” said Charmaine Dahlenburg, manager of the Aquarium’s Chesapeake Bay Program. “It is through our Floating Wetland Island and Biohut projects, and efforts to collect water quality information that we have truly begun to understand our unique urban environment.”

A blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) using habitat offered by the National Aquarium's Biout

To help keep attention on water quality in the Inner Harbor, the Partnership hosts an annual “Floatillla,” a five-mile paddling event that draws hundreds of paddlers to the Inner Harbor in kayaks, canoes, stand up paddleboards, and other human-powered craft. The event presents a highly visible opportunity for paddlers to show their support for cleaning up one of the city’s most treasured and valuable assets.

In the meantime, other waterfront cities are watching Baltimore closely.

“Every single day we are contacted by a different city somewhere around the world wanting to learn about our projects,” said Lindquist.

Much work remains to achieve the goal of a swimmable, fishable Inner Harbor in Baltimore, but the partnership of businesses, agencies, citizens, and organizations devoted to it is growing in strength and size.

“To transform the ecology of the inner harbor we all need to come together- the business community, nonprofit community, and municipal government,” said Hoellen. “That is what we are doing in Baltimore.”

Indeed, as Maryland Congressman John Sarbanes said at the release of the 2016 Healthy Harbor Report card last month, “What we’re getting an A for is collaboration.”

Detroit

The Detroit River is a critical link in the world’s largest freshwater system. Connecting Lake St. Clair and the Upper Great Lakes to Lake Erie, the river provides 80% of the water inflow to Lake Erie and is a source of drinking water for much of the city of Detroit.

Located at the intersection of the Atlantic and Mississippi Flyways, it is an important link in the migratory journey of waterfowl such as the American black duck (Anas rubripes) and Forster’s tern (Sterna forsteri) and raptors such as the American kestrel (Falco sparverius) and Broad-winged hawk (Buteo platypterus). Its bays and wetlands serve as spawning and nursery habitat for fish such as lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) and lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis). And it has, of course, linked the industrial enterprises and cities that thrived along its US and Canadian shores. Cities like Detroit, MI.

As the city of Detroit grew from its 1701 origins as a trading post to the automobile capital of the U.S. in the 1950s, the Detroit River’s shorelines became increasingly hardened to facilitate industry. In the process, the river lost 97% of its historic coastal wetlands on the U.S. side and 95% on the Canadian side. It also had become one of the most polluted rivers in North America, and in 1987 was declared an Area of Concern under the Canada –United States Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. Beneficial use impairments included restrictions on fish consumption, tumors in fish, degraded benthic communities, contaminants in sediments, taste and odor problems, bacteriological contamination, contaminants in ambient water, degraded aesthetics, and loss of fish and wildlife habitat.

In other words, it was bad.

Natural resource agencies from the U.S., Canada, Michigan, and Ontario governments, along with a binational Detroit River Public Advisory Council put together a Remedial Action Plan. But addressing so many serious problems costs money, and in the 1990s, with many of the Motor City’s auto plants gone, Detroit was in severe economic decline. By 2000, the city had lost one-quarter of its population. With the authorization of the Great Lakes Legacy Act in 2002 and the launch of the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, however, funds became available and work to soften shorelines and restore habitat along the Detroit River gained momentum.

Thanks to the efforts of many agencies and organizations in the U.S. and Canada, the Detroit River is beginning to provide ecological connectivity once again. In the city of Detroit, it is providing a new kind of linkage: of people to riverfront. In the process, it is helping the city to generate a new economy and redefine itself as a world-class, international riverfront.

Detroit Riverwalk

To date, 53 soft shoreline engineering projects—projects that use ecological principles and practices to safely stabilization shorelines while enhancing habitat-have been implemented along the Detroit River. Six of them have been along the City of Detroit’s waterfront, a location central to the mission of the non-profit Detroit River Conservancy. Formed with the objective of providing access, improving, operating, and maintaining the Detroit International Riverfront, the Conservancy has been a key player in the revitalization of the city’s waterfront. The Conservancy’s ultimate vision? A continuous, 5.5-mile RiverWalk, complete with plazas, walkways, trails, pavilions, and green spaces that engage and connect people with the Detroit River.

One need only look at one of the soft shoreline engineering projects along the Detroit waterfront to know that the Conservancy’s vision is indeed coming to life. In 2004, a 31-acre brownfield site on the waterfront of downtown Detroit was transformed into Milliken State Park, a thriving waterfront park that provided new access to the river via a public promenade, 52-slip marina, three-mile walking trail, and numerous spaces for fishing and picnicking.

Gabriel Richard State Park

Milliken State Park

As of 2009, it also includes a restored riparian wetland consisting of shallow ponds, emergent/submergent and upland prairie vegetation. Designed by SmithGroupJJR for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, the wetland naturally cleanses stormwater runoff from 12 acres of adjacent land, and provides habitat for aquatic and terrestrial animals, including 62 species of migratory and resident birds that were not present at the previous brownfield. The wetland also educates people with interpretive signage illustrating the native, industrial and social history of the riverfront.

Other areas along the downtown waterfront soft, ecologically functioning shorelines have replaced neglected, industrial edges include: Maheras Gentry Park, where 500 meters of shoreline were restored, an oxbow wetland was created, and native aquatic plants were installed to improve fish habitat; Gabriel Richard Park, where 290 meters of eroding shoreline with virtually no habitat were stabilized and restored, and along the Detroit RiverWalk at Stroh River Place and the Detroit-Wayne County Port Authority, where fish spawning habitat was restored through the placement of limestone riprap. At many of these sites, the restored shoreline not only provides access, habitat, and improved ecological function, but space for engaging programming, such as rain barrel workshops, moonlight yoga, river walks, and birdwatching and fishing events.

The citizens advocacy group Friends of the Detroit River (FDR), has also played an important role in the ecological revitalization of Detroit’s riverfront. Along with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, FDR has led a great deal of ecological restoration work on Belle Isle, a 982-acre island park containing an old growth, 200-acre, wet-mesic flatwoods forest, as well as three lakes, a lagoon, and over two miles of canals. In 1950, the island’s waterways were cut off from the River, causing a significant loss of fish habitat and ecological degradation. As part of a phased program to restore and link those waterways, a restoration project was completed in 2013 to reconnect the lagoon to the river through a breach and two new channels, and in the process, create habitat to support the reproduction and rearing of fish, herpetofauna, migrating birds and waterfowl. The impetus for some of the FDR’s habitat restoration on Belle Isle has been the success of restored spawning reefs just upstream of the island coast led by Michigan Sea Grant. At the island’s South Fishing Pier, for example, the group led the restoration of nursery habitat for larval fish emanating from the restored reefs.

In addition to the spawning reefs off of Belle Isle, Michigan Sea Grant and collaborators have restored spawning reefs at three other locations on the Detroit River south of Detroit, and in three locations in the St. Clair River. This is all in an effort to replace the natural limestone reefs and rocky areas used for spawning by species such as lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens), walleye (Sander vitreus) and lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis) which was largely destroyed with the dredging of the Detroit and St. Clair Rivers. According to monitoring reports, many species have been observed using the restored reefs, including spawning sturgeon.

Juvenile lake sturgeon found on Belle Isle Reef

A major project that has improved public access to the city’s riverfront has been the creation of the Dequindre Cut Greenway, a two-mile, north/south greenway that directly connects the Eastern market commercial district and several residential neighborhoods to the East Riverfront. Part of a plan for a 26-mile greenway that will encircle the city and connect its neighborhoods, the Dequindre Cut was developed through a partnership that included the federal government, City of Detroit, the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan and the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation—and offers a pedestrian link between the East Riverfront, Eastern Market and several residential neighborhoods in between.

Formerly rail line, the greenway is predominantly below street level and includes separate lanes for pedestrians and bicyclists. Near the Detroit Garden Center, which is located along the Cut, peddlers and pedestrians can enjoy native wildflower gardens. The Detroit Riverfront Conservancy is currently designing a pollinator garden along the Cut.

Southwest Detroit is also the gateway to the only international wildlife refuge in North America: the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge. The RiverWalk has also provided connectivity to the 2,400-acre Refuge contains islands, coastal wetlands, marshes, shoals and unique uplands. While the Detroit Heritage River Water Trail provides a water route from Detroit to the Refuge, Hartig believes that the city’s growing riverfront greenway system will one day provide a landward connection.

Kayaking on the Detroit River

“We have a great greenway trail system that is growing every year.” In fact, with recent news that the planned Gordie Howe International Bridge connecting Windsor, Ontario to Detroit will include a dedicated lane for bicycles and pedestrians, Detroit’s waterfront greenway may soon be international.

In addition to the Detroit River Conservancy, Friends of the Detroit River, and the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, key parties in the effort to restore vitality in and Detroit’s riverfront have included the City of Detroit, the Detroit River Public Advisory Council, Detroit Audubon, General Motors, UAW-GM Training Center, Stroh River Place, Michigan DNR, Detroit Future City and countless other agencies and organizations.

“Together, we’re creating green places, but the longer-term strategy is to reconnect people to the river,” said Hartig. “The even longer-term strategy is to inspire and help develop the next generation of conservationists.”

The first phase of the waterfront’s transformation, which was focused on the East Riverfront, is now 80% complete. The Detroit River conservancy is currently working with stakeholders to develop a strategic plan for the West Riverfront. With the Conservancy’s 2007 purchase of a 20-acre property owned by a former newspaper printing facility on the western riverfront, public access to this previously inaccessible stretch of waterfront is now a reality. Based on the progress made so far, more connectivity and ecological enhancement is in store for Detroit’s Riverfront.

Rivard Plaza on Detroit's Riverwalk

The parties involved in the riverfront revitalization are finding new, engaging ways to get people to the river and sow seeds of stewardship. The Conservancy hosts numerous riverfront events and programming, yet they also help create customized programs and partnerships for specific sites. For example, they are currently working with a local school and church to develop year-round stewards for the planned pollinator garden along the Dequindre Cut.