Hartig has received a number of awards for his work, including the 2015 Conservationist of the Year Award from the John Muir Association and the 2013 Conservation Advocate of the Year Award from the Michigan League of Conservation Voters. He has authored or co-authored over 100 publications on the environment, including four books: Bringing Conservation to Cities; Burning Rivers; Honoring Our Detroit River, Caring for Our Home; and Under RAPs: Toward Grassroots Ecological Democracy in the Great Lakes Basin. John’s most recent book, titled Bringing Conservation to Cities, won a Gold Medal from the Nonfiction Authors Association in the “Sustainable Living” category and a bronze medal from the Living Now Book Awards in the “Green Living” category.

I understand that 53 soft shoreline engineering projects have been completed in the Detroit River watershed since the year 2000. You summarized these projects in a paper that was published in the journal Sustainability earlier this year. How do you define “soft shoreline engineering?”

I define it as the use of ecological principles and practices to reduce erosion and achieve stabilization and safety of shorelines, while also enhancing riparian habitat, improving aesthetics, and even saving money.

Soft shoreline engineering along the Detroit River

How many of those projects are along the City of Detroit’s waterfront, and what key lessons have been learned from these initiatives?

On the mainland of the Detroit River, there are six shoreline habitat restoration projects on the waterfront of the city of Detroit: creation of an oxbow and restored habitat at Maheras Gentry Park; restoration of riparian wetlands through a stormwater treatment system at Milliken State Park, shoreline stabilization and restoration at Gabriel Richard Park, restoration of shoreline habitat and access at Mt. Elliott Park, and restoration of shoreline habitat along the Detroit RiverWalk at both Stroh River Place and the Detroit-Wayne County Port Authority. There have been also been soft shoreline engineering projects on Belle Isle, and many more within the Detroit River watershed.

One of the biggest lessons we have learned is that if you’re not actively advocating for habitat and green features, the ship will sail and the shoreline will be either sheet piling or concrete breakwater. We have tried for the last 13 years to be at the table as early as possible.

What is the best way to get a seat at that table?

I’m on the board of directors on the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy, and I have been from the beginning. I encourage my staff to get involved in something that they can help guide and steer, where they can advocate for what we do. It might be a transportation planning study, a city land use committee, or something like that. We need to have habitat experts at the table early on and look for those opportunities. We need to help those involved with urban waterfront development to find the funding sources to add habitat features or contribute to a greenway.

What prompted all of the shoreline habitat restoration along the Detroit River?

All of this restoration work was prompted by the Remedial Action Plan program, a required cleanup program for all Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Areas of Concern (AOC) are sites where significant impairment of beneficial uses has occurred because of human activities at the local level. The Detroit River was designated as an AOC in 1985. Back then, it was determined that we had lost 97% of coastal wetland habitat on the Detroit River, and about 60% of the shoreline had become hardened with concrete break walls and steel sheet piling that has no habitat value. So they (Michigan DEQ, U.S, EPA and a Detroit River Public Advisory Council) put together a Remedial Action Plan for the Detroit River. With the Great Lakes Legacy Act [authorized in 2002, it provides federal funding to accelerate contaminated sediment remediation] and the 2010 launch of the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative , we were finally able to fund some of this much needed work.

Is the ecological enhancement of Detroit’s riverfront still viewed as something that must be done to improve conditions for fish and wildlife, or are people now viewing these projects as opportunities to improve life for Detroit’s people, too?

Yes, they do see it as making life better. This happens when you start by reconnecting people to the water. Then, you have to engage them and get them to see that they are part of the ecosystem, not separate from it. As you educate them along the path towards a stewardship ethic, they start to care not only about the shoreline edge or the river, but about things like stormwater from their yard, or their pesticide use. It’s a long-term process, but all of these things are very important.

In addition to the soft shoreline engineering projects implemented along Detroit’s mainland and Belle Isle riverfronts, there have been sturgeon reefs installed at six locations on the Detroit River. Can you tell us a bit about how the sturgeon reefs are designed and constructed?

With the improved water quality of the Detroit River, resource managers felt that habitat was now the most important factor in limiting sturgeon productivity. Reefs have been constructed at Belle Isle; Fighting Island in LaSalla, Ontario; Fort Malden in Amherstburg, McKee Park in Windsor, Ontario, and Grassy Island Reef. Another reef is scheduled to be built later this year off Fort Wayne. A variety of species have been found to use these reefs, including northern madtom (an endangered species). Sturgeon spawning has been confirmed off the Fighting Island and Grassy Island reefs.

Belle Isle Reef Restoration

What are some of the other, perhaps smaller-scale examples of the integration of ecology into the transformation of Detroit’s riverfront?

There are many pieces of stopover habitat and uses of native vegetation along the Detroit Riverwalk. For example, across from the Detroit Garden Center, which is located along the Dequindre Cut-– a below-grade greenway trail with steep slopes–a developer tore down an old, vacant building and built a parking lot. The Detroit Garden Center has incorporated a one-acre wildflower garden around it’s perimeter. Further along the Dequindre Cut, we are currently designing a pollinator habitat project. We hope to involve a lot of volunteers in the planting and establish a five-year agreement for a local school to serve as the stewards during the school year, and for a local church to be stewards over the summer. Butterfly gardens have also been constructed in Gabriel Richard Park along the Detroit RiverWalk.

A birding event on the Detroit riverfront

Detroit is located at the intersection of the Atlantic and Mississippi Flyways. We collaborated with the Detroit River Conservancy, Detroit Audubon, and Fish & Wildlife to build a birding station on the Detroit Riverwalk to provide an entry level birding experience. We did a bunch of fundraisers and raised enough money to buy four upper-end, permanently mounted spotting scopes. We had a landscape architect create an interpretive panel that helps visitors know what types of birds to expect to see each season. We also program that space by holding a birding event there four times a year.

Are habitat restoration projects along Detroit’s riverfront being monitored?

I’ll tell you two stories–one really good story and one that is frustrating. The sturgeon reef projects have been catalyzed by resource management agencies like the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, USGS, Michigan Department of Natural Resources, and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Those agencies approach the project, from the beginning,

Scientists are at the table designing the reef, they are doing the proper assessment, and they are conducting post-project monitoring of effectiveness. That is awesome! Because of that monitoring, we know that 14 species of fish used the first Belle Isle reef for spawning. We also know that the Fighting Island sturgeon reef in LaSalle, Ontario was successful for lake sturgeon and Northern madtom, an endangered species. That’s a great story.

Lake Sturgeon release tracking

In contrast are the soft shoreline engineering projects. Parks and recreation organizations and private property owners are not in the business of science. They are in the business of economic development or recreation. They do not think about habitat first.

Soft shoreline restoration along the Detroit River in Trenton, MI

One exception is in Wayne County’s Elizabeth Park in Trenton, MI, the oldest county park in Michigan. Here the County took out a breakwater and put in a couple of oxbows, which is awesome, but there is no post-project monitoring of effectiveness. So you don’t really learn from it and you don’t truly know how effective they are. We have to change that. We’re trying to encourage permitting agencies like the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Michigan DEQ to require proper assessment and post-project monitoring. We are trying to encourage partnership agreement with universities and students, and citizen scientists, to perform this monitoring.

Most funders today just want you to build a habitat. They don’t want you to monitor it, and that is usually because of the cost involved. But there are other ways to do monitoring. You can sign an MOU with an NGO or a university and get a grad student to monitor. We have to educate and inspire people to do a better job when it comes to monitoring.

Detroit has so much vacant land now. Is the city making use of vacant land in a way that reconnects people to the river and the local ecology?

Yes. The Detroit Future City initiative, for example, included a pilot effort to transform vacant lots through the use of green infrastructure. Habitat doesn’t have to be 100 acres. It can be small lots. It will take a while, but we are starting to head down that path, and it is exciting.

You are the Director of the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge. What role does the Refuge play in the overall connection of the Detroit Riverfront?

The Refuge [the only international wildlife refuge in North America] extends from southwest Detroit down to the Ohio border, and as far east as Canada’s Pelee Island and Point Pelee National Park. Eventually, the RiverWalk will be connected through greenways to the Refuge’s visitor center. We already have a Detroit Heritage River Water Trail, a canoe and kayak trail that links Detroit to the Refuge. We have a great greenway trail system that is growing every year.

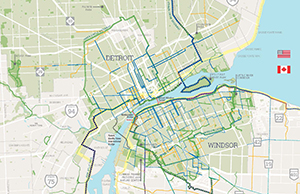

Eventually all of this riverfront will be connected—including to Canada. About two years ago, we created a US-Canada Greenways Vision Map. We knew there were hundreds of miles of greenways in Windsor and Essex Counties in Canada and nearly a thousand miles here in the U.S., but they were not connected in any way.

Our vision was to have a dedicated lane on the Gordie Howe International Bridge for greenways so bicyclists could cross, a ferry that would go back and forth every day that could take people on bicycles, and improvements to the tunnel bus that would enable people to bring their bicycles. Just a few months ago, the Gordie Howe International Bridge agreed to have a dedicated lane for bicycles and pedestrians! We share this river with another country. We need to keep thinking bigger!

The efforts are not just about restoring ecology, but reconnecting the people of Detroit to the river. How important has collaboration been in this process, and who have been some of the key players?

Collaboration is the only way to do it today. One organization cannot do it on its own. You need to join forces. Especially if you are chasing competitive grants, the power of partnerships is strong. Partnerships are critical in an urban area.

In addition to the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy, other key players have included the City of Detroit, Friends of the Detroit River, and Detroit River Public Advisory Council, Detroit Audubon, General Motors, UAW-GM Training Center, Stroh River Place, Michigan DNR, Detroit Future City and many more

Together, we’re creating green places, but the longer-term strategy is to reconnect people to the river. The even longer-term strategy is to inspire and help develop the next generation of conservationists. Eighty percent of all U.S. and Canadian people now live in cities, so the next generation of conservationists and sustainability entrepreneurs will undoubtedly come from cities. Historically, conservation organizations have sort of avoided cities. Now, there is a compelling reason to invest in cities and get people to understand they are not separate from an ecosystem, but part of it. We need to provide people with stepping stones of engagement to get them involved, and then teach them stewardship.

On the Riverwalk, for example, the Riverfront Conservancy does a rain barrel workshop and it sells out every year. They give rain barrels away and people learn about stormwater. We also do a kids-free fishing fest, where over 400 children get a fishing pole in their hands for the first time and get to catch a fish.

We just completed Sturgeon Day, an event where students visit stations and learn about the history of pollution and what we’ve done to improve water quality. People can try their hand at building an underwater sturgeon reef and creating interstitial spaces with rocks, or work with fishery biologists and sampling gear to learn how to do studies. At the end of that event, we bring up a 6-foot sturgeon and people get to take a selfie with it.

I understand that you grew up in the Detroit area. What does it mean to you to be involved in the effort to bring this river back to life?

As a kid, I saw it at its worst. I remember when you couldn’t eat any of the fish from the river, and you’d see grease and oil floating on it. I saw the Rouge River catch fire. What is happening now is just so heartening. What an awesome opportunity to be part of the revival of the Detroit River, helping to reconnect people to it, and teaching a stewardship that will make a difference.