Here in the US, recent news that the President intends to pull out of the Paris Agreement (which commits countries to holding global temperature increases to “well below” 2C above pre-industrial levels) has been met with a combination of dismay, frustration, and willful resistance by many individuals in the environmental community. Most prominent among the resistance is the movement by many municipalities, institutions and companies to stand up and say that we will hold to the Agreement even if our government refuses to.*

This was weighing heavily on me as I began reading Dr. Iain McCalman’s book The Reef: A Passionate History of the Great Barrier Reef, from Captain Cook to Climate Change. The Great Barrier Reef (GBR) is an ecosystem especially sensitive to the implications of climate change.

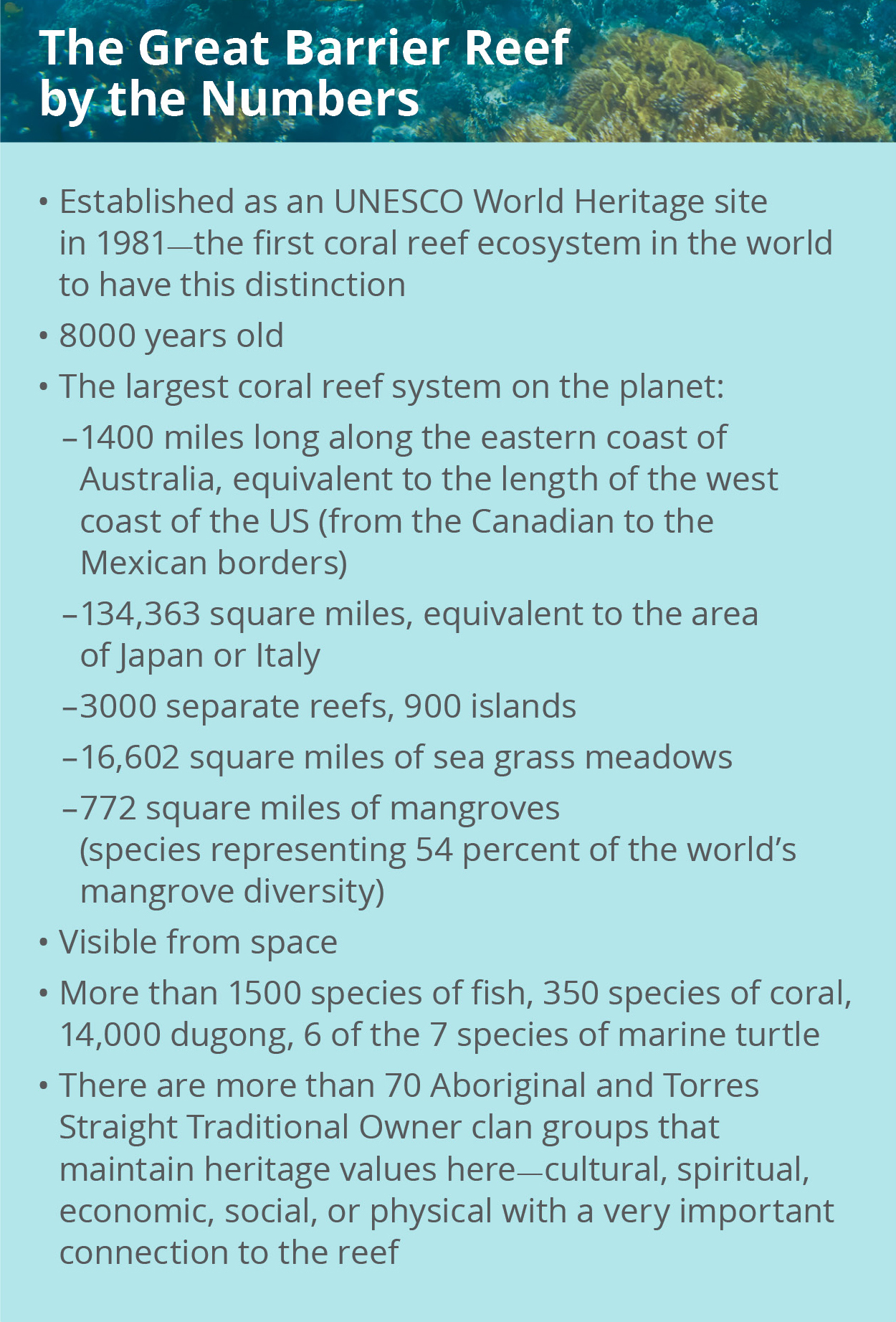

The dramatic temperature increase of our marine waters, along with sea level rise and increased storm frequency, have immediate impacts on the health and long-term sustainability of reef ecosystems worldwide.

In Australia, as recent as this March, a bleaching event affecting over 2/3 of the Reef was spurred on by warmer water temperatures, the second such mass bleaching in as many years. Approximately 1/5 of the bleached coral is feared dead.

As Dr. McCalman so elegantly describes in his book the Reef is a place animated as much by human perception as by its complex dynamics as an enormous marine ecosystem, inextricably linked to the landscape of eastern Australia and the people who have lived there. And that, at its core, is what may be the only thing to save it and other sensitive ecosystems on the brink: the emotional connection we invariably feel as we come to know these incredible places through stories, art, and detailed information about their unique and important roles in our existence on this planet.

McCalman’s book is no ordinary natural history. Rather he takes us on a journey of the Reef through the lens of biography. This begins with the first published accounts of Captain Cook’s initial voyage along the eastern coast of Australia and ends with the present day work of scientist and environmentalist, Dr. Charlie Veron, who has worked tirelessly for most of his career to chronicle the impressive diversity of coral species and work for the preservation of coral habitat.

Through 12 chronological stories we navigate the once unknown waters of the Reef lagoons, learn the tales of shipwrecked Europeans rescued by Aboriginal tribes who considered them “ghost people,” hear from the first men and women to categorize the important and unique characteristics of the Reef ecosystem and the study of ecology itself, and learn of a rich history of artists and storytellers that helped usher the lush landscapes and vibrant seascapes into the popular imagination and fight for its right to persist in light of development and extraction pressures.

One such story was “War: A Poet, a Forester, and an Artist Join Forces” in which we learn of an unlikely alliance between poet Judith Wright, forestry scientist Len Webb, and artist John Busst. In the late 1960s they successfully fought against a sugar cane farmer’s application to dredge and mine an isolated part of the Great Barrier Reef- because he claimed it was dead.

With the help of marine scientist and director of the Australian Conservation Foundation, Dr. Don McMichael, who was willing to testify in court, they were able to prove that the Reef was alive: teeming with 190 species of fish and 88 species of live coral. The local court was persuaded against the mining application and this small victory “marked the moment when the Reef became a central cause for conservationists all over Australia, and it unleashed a fourteen year campaign to save the reef.” It was their sense of wonder and respect for the natural world that fueled these individual’s tireless advocacy through art, literature and science. Their life-long efforts to establish a sanctuary marine park that preserved the Great Barrier Reef from destructive drilling and mining would be completed in 1979 with the creation of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

As McCalman notes at the beginning, “it is only by melding our specialized scientific understandings of the Great Barrier Reef with the ideas it engenders – the sensory, the spiritual, the aesthetic- that we will fully appreciate why it demands we be its global caretakers.”

I reached out to Dr. McCalman after I finished the book to see how and if things have changed for the Reef recently. I was curious if recent urban development efforts in Queensland have included coastal shoreline restoration or innovations that protect the Reef and the broader ecosystem health. I had heard about the bleaching and assumed the Australian people must be on the leading edge of such innovations to preserve and protect this natural wonder and important attraction. Not surprisingly it is not as simple as that. There are many competing interests, economic drivers, and pressures on the Reef, much of it complicated by regional and national politics.

In addition to being an author, McCalman is Research Professor in history at the University of Sydney and co-Director of the Sydney Environment Institute, so his effort to chronicle the Reef’s past and sound the alarm for its future is not just an academic endeavor, it is personal and urgent. Since the book was published he has continued to work to get the message of the Reef out to the public through videos and speaking engagements, and through further interdisciplinary dialogue at the Sydney Environment Institute.

He explained that while the threat of destruction from oil and gas drilling has been limited, other extractive industries continue to threaten the Reef. First and foremost among them is the recently greenlighted Adani Mine, in the Galilee Basin in Central Queensland. This $16 billion thermal coal mine will require the clearing of floodplains and ag land for a new rail line to the coast, the expansion of the Abbot Point Port and the likely destruction of sensitive coastal habitat including mangroves and tidal flats, and increased pressure of active shipping lanes that weave through the Reef lagoons and perilously close to the corals. According to McCalman this new coal mining operation will potentially expand the number of coal ships from 14,000 to 85,000 (a factor of 6!) and will become the “7th largest CO2 emitter in the world.”

Shipping lines and coal export ports along the Great Barrier Reef.

It is hard to believe that the government would approve this development given the sensitivity of their most precious resource to the impacts of carbon dioxide on the environment. In fact the Great Barrier Reef tourism industry is worth up to $6 billion annually and employs over 70,000 Australians, and yet the argument the state government makes is that this is good for the economy. But the Australian people continue to fight this effort, and speak out against the proposed mine.**

McCalman expressed hope that ecological restoration successes in other locations will help citizens see the potential for a role they can play. In Sydney Harbor a successful restoration of the native crayweed (Phyllospora comosa) provides important habitat for abalone and crayfish. The success is notable because the crayweed had not been able to regenerate on its own after improvements to water quality in the harbor, but with the aid of scientists’ innovations in seeding the plant this kelp species (known for its extensive “underwater forests”) is making a comeback.

Seagrass and mangrove restoration has also been successfully implemented, the former is especially important as it is known to absorb CO2 at a rate 40 times faster than rain forests and provides an important feeding ground for key species including the dugong, turtles and dolphins. But the restoration of the rain forests in Queensland are important too, McCalman notes, “the reef is interconnected with the health of the rain forests, and these are Gondwanaland forests” some of the most ancient forests in the world.

Not too dissimilar to Judith Wright and her collaborators, McCalman and his colleagues at the Sydney Environment Institute are bringing together the sciences, the humanities, and the arts to demonstrate to broader audiences the many processes and perils of current policies and practices in the Great Barrier Reef and other sensitive ecosystems along the coast. It seems a personal mission for him, to better communicate “the emotional cost of what we’re doing.” As he so poetically entreats at the conclusion of his book, “we need both heart and mind if we are to meet the challenges that confront this unique country of sea, island and coral that we call the Great Barrier Reef.”

Special thanks to Dr. Iain McCalman for spending time speaking with me about his book and Fabien Dubas for sharing his photography of the Queensland coastal ecosystems.

*Biohabitats is among the signatories to this pledge

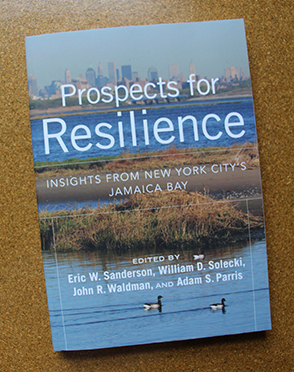

Prospects for Resilience: Insights from New York City’s Jamaica Bay, Edited by Eric W. Sanderson, William D. Solecki, John R. Waldman, and Adam S. Parris

Review by Terry Doss, senior ecologist & Hudson River Bioregion team leader

One of the features I like most about Jamaica Bay and the communities surrounding it is how, despite being part of New York City, it feels so different and, at times, so far away from the city.

After a day of kayaking on the bay or surfing on the Rockaways, I am always stunned when heading north over the Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge to see the City skyline looming so close.

But, as illuminated by Superstorm Sandy, Jamaica Bay and its environs are very much a part of the City and have the same issues that typically plague a city – pollution, poverty, failing infrastructure. And it’s these vulnerabilities which came to the forefront in the aftermath of Sandy.

Sandy hit the Jamaica Bay communities hard and created an urgency to begin the discussion of how to create more resilient communities. This is not a problem unique to the Jamaica Bay area – many of our major cities were built along the coastline and all are trying to develop strategies for dealing with typical city issues while also dealing with the realities of climate change and rising sea levels.

The collaborative strategies presented in Prospects for Resilience: Insights from New York City’s Jamaica Bay, a new book published by Island Press, provide a path for other coastal cities to follow in determining how to advance resiliency in diverse, urban communities.Through a series of 12 papers authored by a number of researchers, resilience is discussed as a process and the writers walk the reader through the process, in great detail, as it applies to the Jamaica Bay area.

Volumes of research have been conducted on and about Jamaica Bay, but it is often disparate or specific to one topic or community. Prospects for Resilience connects the pieces, showing the interconnections between the social and ecological practices, and providing best practices that can be adapted to develop community resilience framed through a socio-ecological lens.

The authors note that, while Sandy created hardships for most residents around Jamaica Bay, it also provided “an opportunity for some communities to pull together.” The hope is that these renewed connections will instill greater resiliency in the face of future threats.

What I appreciated in this book was the variety of voices and perspectives that carried forth in each chapter, as well as the considerations of the various communities such as Far Rockaway, Broad Channel and Canarsie and how the character of these diverse communities lent a different perspective to their views of Jamaica Bay and just what resiliency might be.

For example, there are communities around the bay where most residents moved there to be near the water, while there are other bay communities comprised primarily of public housing, where residents likely live there for economic reasons. These isolated communities each have a dissimilar sense of priorities for resiliency both now and into the future.

Jamaica Bay

So how to overcome these isolated priorities and diverse understandings? The authors point to the Science and Resilience Institute at Jamaica Bay as the leader that will work across boundaries to connect science, policy and practice as well as build models for and monitor conditions in the bay.