In 2006, when Jason McLennan left a successful architectural practice to devote himself to taking the green building movement beyond LEED Platinum, he certainly disrupted status quo for sustainability. The framework he created, the Living Building Challenge, is now the most stringent and progressive green building program in the world.Today, as a designer, consultant, and thought leader, McLennan works closely with world leaders, Fortune 500 companies, NGOs, major universities, celebrities and influential development companies –all in the pursuit of a world that is socially just, culturally rich and ecologically restorative. In addition to creating the Living Building Challenge, McLennan was a primary author of the WELL Building Standard, a rating system focused on the impacts of buildings on human health and wellness. He is the author of six books on sustainability and design, including the Philosophy of Sustainable Design, which is considered the ‘bible’ for green building. He serves as the Chairman of the International Living Future Institute and is the CEO of McLennan Design, his own architectural and planning practice. Through his buildings and his written work, which has been published in dozens of journals, magazines, and newspapers around the world, Jason McLennan is demonstrating what true sustainability can be.

Jason McLennan

How did you come to conceive of the Living Building Challenge?

I was working with Bob Berkebile in Kansas City on some of the greenest projects of the time anywhere. Our goal was to define what a truly sustainable building would be and not merely a less bad version of what was typically done. It’s around that thinking that I coined the term “Living Building” and began working on this idea. Many people gave me ideas and thoughts that contributed to this thinking.

It must be incredibly rewarding to see your idea come to life. Do you have a favorite Living Building?

Not really. Seeing the whole movement take off is truly the most rewarding thing. I do love my house–Heron Hall, though.

Heron Hall

The Challenge continues to evolve based on the feedback of those pursuing it. Has any of this feedback really surprised or changed you?

I can’t say that I have been surprised, because I understood the industry when I created it. I understood where the LBC was going to get push-back and where things would likely be adopted. It really marches along as I hoped it would – perhaps that’s the surprising thing, that it went according to plan!

How do you define “Regenerative Design”?

Regenerative design is centered on the idea of trying to improve the conditions for life within the places we are working. With every building and every design, the world should be better off for it having happened, as opposed to worse off. Design is an act. It’s the process of unveiling solutions that will make the world different than it is today. Regenerative Design makes it better – more healthy, vibrant and alive.

Pattern recognition is one thing you recommend for those practicing regenerative design. What do you mean by that?

For too long, we have not been thinking about the consequences of the designs we create. We don’t recognize that when we do things a certain way, there is a ripple effect upstream and downstream.

The idea of pattern recognition is to deliberately hone in on the interconnections and patterns that exist all around us, to recognize that when you tug on one end of the rope, there is something on the other end that moves or doesn’t move. We also need to expand the geographic boundaries of the patterns we’re looking at. Within the building industry, when we do look at patterns, we often look only at patterns that are close at hand or patterns that impact humans directly. We don’t look so much at the patterns that might impact other species or the greater web of life. When we practice pattern recognition in regenerative design we have to try to zoom out as much as possible and keep asking questions, like “What is the outcome of this decision? What is the likely trend that will occur? What else and who else will be affected and how? What if we did something differently?”

How broadly do you zoom out? Do you look at things like, say, migratory flyways?

Yes. For example, when most building designs are happening, designers are asking questions like, “How much water do we need and what size fixtures do we have?” We try to expand that process to understand the hydrology of a place. We want to understand how water moves on a site, what the function of the water on the site is and what forms of life it supports. We want to look at the quality of water that comes in and out, the impact of that quality on those that come into contact with the water. A much broader and wider group of questions get asked for each issue, and water is just one issue. It really is about expanding the sphere of what we need to know and understand.

You can’t help but understand interconnections if you want to achieve the Living Building Challenge. With a project like the Bullitt Center in Seattle, we were ultimately concerned about impacting salmon. Everything in Seattle flows downstream and ends up in the Puget Sound. Every single building in Seattle either contributes to the health of salmon, orcas, and everything in the Sound, or diminishes it. These interconnections inform design for stormwater runoff, rainwater catchment, greywater treatment, and parking. Zooming out to look at downstream impacts is part of every project that goes through the Living Building Challenge.

What motivates clients to pursue the LBC?

The first group of clients have been very self-selecting. They really care about the environment, and they’re trying to express their values in the buildings they are creating. The Living Building Challenge philosophy fits their ethos, and that has really been the driver with the early adopter group. That is still the case, but people are starting to recognize that there is a value in addition to that: reputation, attracting people (including funders) to a project, good PR, economics.

What about the beauty of Living Buildings? Beauty is one of the LBC’s seven petals. Is it becoming more of a motivator for clients to pursue the LBC?

Beauty is essential to the uptake of any idea. We don’t judge something to be successful if it’s not elegant or pleasing to interact with or be around, and ultimately, it’s not sustained if people don’t love it. It’s something that the green building movement forgot about and did not have in the equation, and the results were wrong. It was something that I very deliberately wanted to inject into the conversation, to get people thinking.

Your 2016 book Transformational Thought II includes an essay entitled “A Sustained Awakening of the Human Heart: Love and Green Building.” What does love have to do with the Living Building Challenge?

Everything, really. I’m actually turning that essay into an illustrated book, Love and Green Building that will be made available through Ecotone Publishing in 2020 and available on Amazon and other retailers. Love is the motivating force behind why we do things that are hard. It’s because we care.

I noticed a recurring theme in your writing: the fine line between hopelessness and hopefulness, action and inaction, pessimism and optimism, human worthlessness and human potential. You admit that even you have good days and bad days. What keeps you in the positive?

If you are only happy, you’re being delusional, and if you are only sad, you are not able to contribute to society in a productive way. Both ends of the spectrum are unhealthy. Being able to walk that line is really the challenge that we have if we want to be changemakers. It is not easy to stay on the right side of the line.

I have wonderful people around me, and I live in a beautiful place, so those are buoyant forces that lift me up. Again, it’s love that lifts you up. Working on relationships and yourself is fundamental if you’re going to stay on the right side of that line.

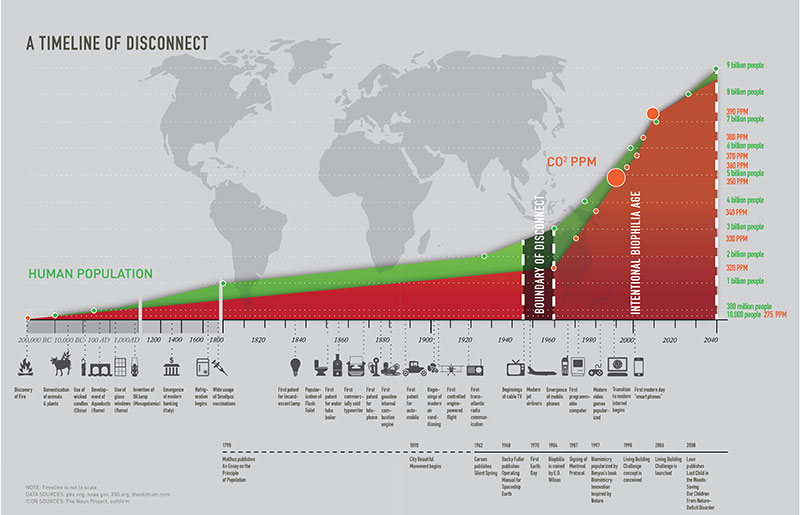

You have written that sometime between the end of WWII and the 1960s, we crossed a “Boundary of Disconnect,” when we began disconnecting our actions from their environmental consequences and became disconnected from nature. How far past that boundary have we moved, and what role can the LBC play in helping us to cross back over?

The Boundary of Disconnect also refers to where we had the science and knowledge that we were in fact doing this, but we did nothing about it. Humanity has been disconnected from our impacts for a long time, but either the impacts didn’t matter too much in the grand scheme of the planet or we didn’t understand it. But we have known for some time what we’ve been doing. We’ve known about climate change and the impacts of habitat loss, but as a society, we’ve done nothing. In fact, we’ve just accelerated our negative impacts. Evidence coming in every month now shows us that we are quite far past the Boundary of Disconnect. We are in a very dangerous place that we weren’t necessarily in ten years ago.

Graphic courtesy of Trim Tab

I always had a two-pronged approach to the Living Building Challenge. The first, which was probably too optimistic was, “We’ll show people how to do Living Buildings and people will just start doing them everywhere.” That is, of course, not happening. Most buildings are not even LEED buildings. The second part of the strategy was to begin building the models, and when we were ready as a society—when it became so obvious that the planet was collapsing, and we had to change—we’d have 30 years of evidence that we can build this way. We’d have the knowledge and models to turn to.

That is where we are with the Living Building Challenge. These buildings are like pilot projects. Living Buildings are models for the future when the future is ready.

Communication is so important in regenerative design. What have you found to be the most effective strategy to get others to see what is possible when one adopts a world view in which people participate in the cycle of regeneration as they create buildings?

For people who are ready, they just have to be exposed to the right ideas and opportunities, which is where Living Building Challenge comes in. But there will always be whole groups of people who will never give a shit, and there is a whole mass of population that thinks it’s not their job to do this stuff. We need systemic change. We are not going to succeed if we have to change everyone’s world view. People need to live in a world in which it’s easier to do the right thing than the bad thing because of the systems that have been put in place. You have to get enough people to understand and move, and that is where the powerful models come in.

Co-creating Living Buildings requires a focus on “potential” rather than “deliverables” and a real exploration of the core purpose of the work. One thing you recommend is beginning a “co-creative relationship” by asking clients “gently destabilizing questions.” Can you give a few examples of such questions?

Sometimes I’m more gentle than other times. But I’d say it’s more about trying to challenge assumptions that people make. It’s an intuitive process. When you sense that there is a barrier to a better path, you have to pursue it and get to the root of it. Sometimes doing so is uncomfortable and can be very personal so the relationships have to be there. To be effective, it has to be done in a spirit of caring and in service of the larger outcome.

I was intrigued by your discussion of the Amish and Mennonite concept “Ordnung” (order) and how it is used to guide decisions those communities make. How does the concept of Ordnung relate to the Living Building Challenge?

The point of the Ordnung, which is powerful, is the fact that you have to stop and consider what something will do to our lives, and whether it preserves or undermines our values. Amish and Mennonite communities have had remarkable success in [maintaining their way of life] despite the pressures of modern society around them.

We don’t discern much at all. Couldn’t we be more discerning? The Living Building Challenge asks people to be discerning around the things that go into buildings, what their chemical composition is, and what their impacts to human and ecological health could be.

You and Bill Reed say that we must “fall in love with nature” to truly understand the essence of a place. For those of us in ecological restoration and conservation, this is probably an easy courtship. But how do you get your clients, funders, contractors, and other collaborators to “date and fall in love with nature?” Are there any unique methods you have used or seen others use in LBC teams to do this?

Many of our clients have already fallen in love with nature and life, and that’s why they are coming to us. In general, the only way to help someone truly fall in love with nature is to expose them to it. We can do a good job of sparking peoples’ curiosity through the written word and through speeches, but people really need to be out in nature.

I think we are all born attracted to and ready to love life. But society beats it out of our kids, and technology becomes a surrogate. Technology can be like eating junk food. It’s more calorie dense, and you get this sugar rush, so the reptilian brain rewards you and says, “Do more of that!” Ultimately, healthy food gets pushed aside, and then you start to get sick.

Let’s say a Living Building Challenge design team has a project located within the watershed of a river but nowhere near the river. Would you recommend that the design team, clients, and stakeholders canoe down the river?

Absolutely. Understanding of place is a big part of what we do, so getting your clients out into nature and getting them to understand how their sites work is critical. Sometimes we need to bolster our own understanding of how an ecosystem or hydrology is working so we bring in ecological consultants to help us and our clients understand what we are seeing. Love grows more deeply when you understand something more deeply.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on several living building projects at different scales – the world’s largest higher education LBC project at Yale, a new corporate HQ that will be a living building, a couple houses and more!

McLennan Design, in partnership with EcoLock, is designing a new typology of Net Positive storage facilities.

What advice do you have for ecologists who would like to become more involved in the creation of Living Buildings and Living Communities?

Show up! There are many ways to get involved, and the best way is to reach out to ILFI and volunteer and come to events like the Living Future Unconference. www.living-future.com