The Living Community Challenge

By Amy Nelson

David has collaborated on two registered Living Community Challenge projects, providing visioning and conceptual plan input related to restorative water systems and ecology.

As part of its ongoing work to promote and quantify restorative buildings and sites, the International Living Futures Institute (ILFI) has continued to refine, evolve, and build upon the Living Building Challenge (LBC) certification program. One inspiring way they have done this has been the creation of the Living Community Challenge, a framework to integrate regenerative design strategies and metrics at the scale of a neighborhood, campus, or district. Launched in 2014, the LCC considers an entire community an ecosystem and strives to optimize the whole system rather than its individual parts. In other words, if a Living Building functions with the elegance and efficiency of a flower, a Living Community functions like an entire wildflower meadow. A Living Community is rooted in place and adapted to its climate and site. It harvests its own energy and has closed-loop water cycles. In a living Community, waste is regarded as a resource, and diversity is a strength.

Overview

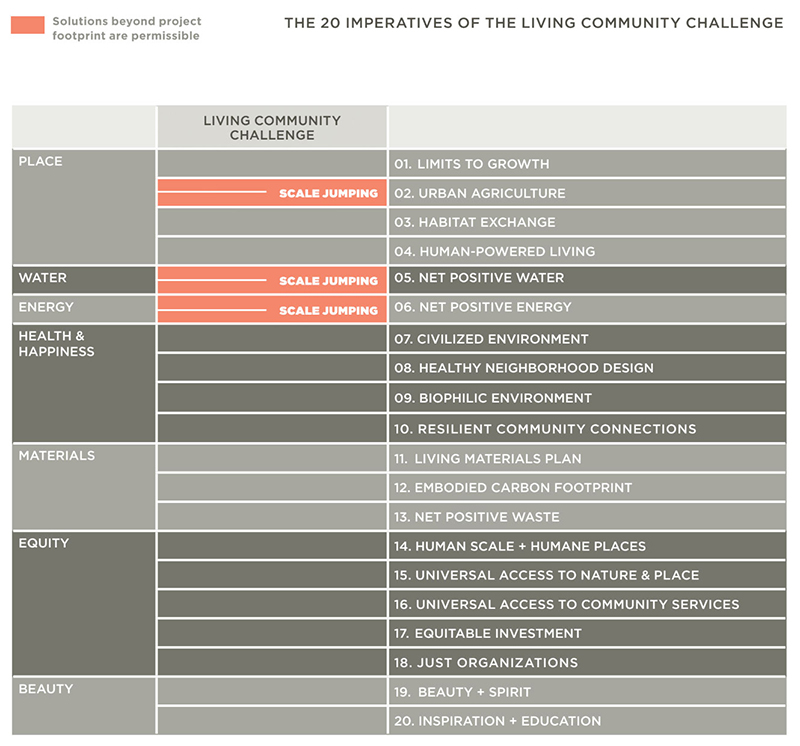

In complete alignment with the LBC, the LCC strives to promote and demonstrate patterns of development that are restorative to the ecology of the site and the people it will serve. By addressing aspects such as walkability, affordable public transit, and universal access to community elements and services, the LCC expands the spirit and ethos of the Living Building Challenge well beyond the individual building/site scale. LCC projects have a diversity of uses, provide access to the essential components of livability (places to eat, sleep, work, play, and where services are provided), have multiple buildings, and include at least one multi-modal street. Shared infrastructure (energy, water, streets) is optional. Like the LBC, the LCC is a Standard (currently 1.2), structured around performance area “Petals,” with each Petal containing a set of “Imperatives.” As with the LBC, Imperatives are mandatory, and project certification is based on actual, rather than modeled or anticipated performance. The seven performance Petals of the LCC and their basic intents are:

Place: Restore a healthy interrelationship with nature.

Water: Create developments that operate within the water balance of a given place and climate.

Energy: Rely only on current solar income.

Health & Happiness: Create environments that optimize physical and psychological health and well-being.

Materials: Endorse products that are safe for all species through time.

Equity: Support a just and equitable world.

Beauty: Celebrate plans that purpose transformative change.

Certification Process

The ILFI realizes that community-scale initiatives can take years or even decades to fully realize, and since full certification is based upon measured performance, the certification process provides a sequence of interim steps and resources to offer project teams the greatest potential for success. Aspiring LCC projects are registered with an application and fee, which provides access to ILFI staff expertise and guidance, along with project exposure. Each LCC project begins with a planning process that ultimately leads to the submittal of a Master Plan. Depending upon the time frame, context, stakeholders, and other items, the planning process can be split into an initial Vision Plan phase, which is then followed by more comprehensive, detailed Master Plan that is reviewed for compliance with the standards. Once the Master Plan compliance has been confirmed, the project is classified as Emerging, a designation that remains throughout the Implementation phase. The time frame of the Implementation phase can also range widely. Once completed, full certification can be sought; individual Petals can be certified independently; once a Petal is achieved, it becomes a Certified Petal Community, and then when all seven Petals are certified, then a full Certified Living Community. There is also a compliance path for a Certified Zero Energy Community.

Registered Projects

There are currently over twenty LCC projects that have engaged with the program during the Pilot stage (Exploratory), and/or have become Registered since full certification became available. These projects are all in various stages of the planning process, many of which are listed with a brief description on ILFI’s website.

One such project is Veridian at County Farm in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Located next to an expansive county park with trails that wind through re-naturalized agricultural fields, woodlands, and gardens, Veridian at County Farm is an inspiring, regenerative community being planned by THRIVE Collaborative, a development firm with a mission to create ecologically restorative housing, and Avalon Housing, a non-profit that provides healthy, safe, and inclusive housing for the homeless. Envisioned as one of the first mixed-income net zero energy communities in the U.S., resilience was one motivator for pursuing the LCC.

“We will be defined not by the unsparing consequences of climate change, but by how we respond to them as our window of opportunity for action closes,” said THRIVE Collaborative founder, Matt Grocoff. “Veridian at County Farm is an act of optimism, and the LCC provides us an inspiring framework to share with the community.”

The all-electric neighborhood will be powered by solar, with no gas lines of combustion appliances. “The most devastating thing any investor can do for their portfolio is to ignore where a market is heading,” said Grocoff: ”It’s deviant to consider designing a neighborhood that does not include the complete end of the burning of fossil fuels.” Among other amenities, Veridian at County Farm will include a multifunctional community barn, greenhouse, coffee shop, farm store, and other spaces where residents can gather, play, access social services, and avoid the isolation felt by many in new developments. It will feature greenways designed to improve social interaction between neighbors, and lanes/pathways that integrate green infrastructure to manage stormwater. Biophilic/walkable urban design elements include front porches facing greenways connected with miles of wooded trails.

“doing ‘less bad’ is no longer going to cut it”

“As we all know, doing ‘less bad’ is no longer going to cut it,” said Grocoff. He believes the team’s commitment to the LCC helps to ensure that Veridian at County Farm will be more than a sustainable neighborhood. “It is a platform to stoke our capacities for collaboration, creativity and compassion,” he said. “We wish to demonstrate how forward-thinking local governments can engage their own citizens, private and non-profit, to overcome seemingly insurmountable problems and achieve sustainability and equity goals more effectively.

Veridian at County Farm’s restorative landscape approach incorporates native trees, shrubs, and perennial grasses managed as a system to provide habitat, water balance, and beauty. It also dedicates 30% of the landscape to local food production.

One of the main challenges of creating a Living Community, according to Grocoff, is the lack of alignment between the goals and values proclaimed by many state and local governments, and their existing regulations and codes. “We cannot continue to play by the old rules,” he said. “They don’t work.”

Creating an LCC is indeed no cakewalk, but according to Grocoff, it is an invaluable journey for any developer with an eye toward the future. “2019 has seen a global awakening about the consequences of climate crisis among consumers, governments and corporations. There is growing pressure, financially, ecologically and politically to offer products that exhibit leading edge sustainability,” he said. “The LCC offers something more than a just a sound investment opportunity; it offers visionary leadership and a crucial path forward for the future.”

Another project aiming for LCC certification is Maitland Tower Imaginarium, a 6.25-acre community located along the St. Lawrence River in the tiny village of Maitland, Ontario. The site’s history dates back to original French settlement in the 1700s. It has been used as a shipbuilding fort, flour mill, bootlegging distillery, a submarine sonar chart-making company, and a horse-drawn carriage stable. Its owner, Philip Ling, envisions the community as a place devoted to stimulating and cultivating the imagination toward scientific, artistic, commercial, recreational, and spiritual ends.

Ling purchased the property to protect, preserve, and interpret its amazing history, and prevent it from being developed with conventional approaches. After restoring an historic stone tower reconstructing an adjacent structure, Ling spent several months reflecting on his vision for the site. He concluded that the LCC was the ideal framework for achieving it.

“I like the Trojan horse aspect”

In addition to aligning with his personal values, the LCC appealed to Ling because of it’s potential to stealthily shift paradigms. “I like the Trojan horse aspect,” he said, “where the transformational goal is not something people have to have in their face, as it would create resistance to change, but it is there.”

Initial plans for the community include a Marine Research Center, a Biomimicry-based Technology Incubator Hub, a Zen/yoga/recharge space, biodynamic farming, beekeeping, and spaces to celebrate music and water.

Though the amount of time, funding, and leadership it will take to establish, nurture, and shepherd his vision to reality is a concern for Ling, he remains undaunted in his pursuit of the LCC. “The LCC creates the framework for a healthy thriving community–a model for a sustainable future with enough economic success to secure long-term viability,” he said. “Achieving that is my measure of success.”

For Ling, the LCC has not only provided an aspirational goal with a clear framework and support network for establishing a regenerative community; it has created community in the process. “The LCC has created a public framework that you can point to show that you are not alone,” he said, “that there are others who embrace the same holistic goals towards a healthy future.”

A very compelling example of an LCC in progress is the Reserva Santa Fe project in Estado de Mexico, Mexico. Situated within the last remaining stretch of relatively preserved forest between Mexico City and the city of Toluca, the remote, 536-acre site is an important ecological corridor, but it has suffered from poor management and overharvesting. The temperate mixed forest has also been weakened by drought and threatened by pests and parasites that have migrated from lower elevations in response to climate change. In addition to its ecological significance, the Reserva Santa Fe property has been deeply intertwined with the social and cultural richness of the region. Previously owned by small-scale farmers, the site contains a sacred sanctuary used by the region’s indigenous Masahua and Hñähñú, ñacaltura otomiñhó, ñathño ñ’yühü (“Otomí”) people.

Though the LCC’s first Imperative, “Limits to Growth” requires projects in developed countries to be built on brownfields and greyfields, it does allow communities in developing countries to build on greenfield sites as long as they permanently conserve (through a partnership with a reputable land trust) twice as much land on or adjacent to the community.

Rather than pursue an exploitative, “buy cheap, sell high” mode development, which sadly is common in the area, Reserva Santa Fe owner/developer Armando Turrent chose a different approach.

“We came across this beautiful tract of land and immediately felt compelled to find a way to make a truly sustainable residential community that could halt the ever-growing squatter problem that systematically clear cuts and invades national and state parks on the western outskirts of Mexico City,” said Turrent. With Reserva Santa Fe, Turrent aims to protect and restore, rather than degrade and destruct, the region’s ecology and culture.

Before drawing up a single plan, Turrent sought to understand the property’s ecological and cultural significance. He began by inviting the landowners from whom he acquired the property to become partners in the development. Working with ecologist and integrated design specialist, Juan Rovalo (now a member of the Biohabitats team) he initiated a baseline assessment of the health and vulnerability of the forest. participated and coordinated studies and inventories on vegetation, fungi, pests, and parasites, and measured populations of birds, reptiles, and amphibians. In addition to identifying the parasitic mistletoe plant as key threat to the forest, the study revealed the presence of an endemic salamander species. Turrent took action to begin protecting and restoring the forest. He met with the state forestry agency to encourage the development of more sustainable harvesting practices.

He worked with a local landowner to create a native plant nursery to propagate and supply native plants for forest restoration and Reserva Santa Fe landscaping. He and Rovalo provided job training to members of the community who began removing mistletoe and other parasites from the forest by hand. He also brought an ecologist on staff to focus on the ecological integration of all aspects of the development including the creation of wetland areas in Reserva Santa Fe. He is currently working with federal authorities to declare the forests at Reserva Santa Fe a “private preserve area,” which would give the right to restore and enforce a forest management plan that already in effect.

Turrent was equally dedicated to understanding and safeguarding the site’s cultural significance. “Right in the middle of our forested area there is a sacred space were the Virgin of ‘Los Remedios’ appeared over 200 years ago on top of a rock,” said Turrent. “Since then, the Otomí and Masahua show up to pray and venerate the Virgin.” The sanctuary’s protection was critical to him, especially since it was not be protected by any government agency or law in Mexico. Building a trusting relationship with the indigenous community required time and patience. Turrent described the first time he met the Otomí leader of the sanctuary:

“After we were introduced, he gave me a copy of the Pocahontas movie to suggest we avoid a colonial type of conquest. He firmly believed that the land where the sanctuary was belonged to the Virgin, disregarding our title to the land.”

When Otomí ultimately recognized that Turrent wanted to save the sanctuary, ensure their access to it, and benefit the forest, they began having conversations with him. After two years of patient negotiations, they reached a mutual agreement

“I agreed to help them build a temple, designed by them, that would venerate the virgin. I also agreed to participate in five rituals at different mountaintops to commit to them and the Virgin, that entrance to the sanctuary would be allowed in perpetuity to all users. I also pledged to preserve the forest. In return, they would recognize our title to the land and agree to access the temple observing certain rules and regulations and would support our project,” said Turrent. The Otomi and Masahua peoples, who have protected and used the forest in a sustainable way for centuries, also agreed to pass much of their knowledge of the land and help Reserva Santa Fe stand up to any neighbors that may endanger the forest.

Guided by Otomí’s exact specifications, Turrent constructed an open, ring-like structure around the sacred site. It’s design not only venerates the Virgin and communicates the stories of the Otomí, but also captures rainwater which is then piped directly to those communities for their use.

According to Turrent, LCC process helped him develop and articulate his vision in concert with the local community. That vision includes housing, a community home, low-impact infrastructure, recreational facilities, greenhouses, and an organic farm built with the highest environmental aspirations that foster a culture that protects local traditions and the sense of place. “The LCC, he said, “validates us as atypical developers.”

The project is now one of only two LCC projects deemed Vision Plan Compliant, meaning that the vision plan meets the criteria of the LCC at a very high, conceptual level.

As with LBC projects, the Materials Petal challenging. “Finding Red List replacements in Mexico has been very difficult,” said Turrant. The Equity petal is also proving to be a challenge. “The ‘no gated communities’ part of the Universal Access Imperative has been a real challenge given Mexico’s spiraling crime and violence waves of the last decades,” said Turrent. He remains committed, however, to providing people from all social classes with access to the community’s many public and green spaces, and will do so while incorporating some safety checks. Regardless of the challenges, Turrent sees a market for a regenerative community. “Fresh air, clean streams, ponds, and lakes, running trails in the woods, darkness at night…all these commodities are highly valued in Mexico City,” he said.

“Very few people in Mexico know of LEED, and only a small fraction of those people have heard something about the LCC,” said Turrent. That lack of awareness, however, does not seem to be impacting Turrents ability to generate interest in Reserva Santa Fe. “When people hear about the efforts we must endure to get LCC certified,” he said, “they feel protected by this foreign institution that will not allow us to sway from creating a truly sustainable community.”

“The process will change the way you approach and solve problems”

When it comes to pursuing the LCC, Turrent advises other developers, “Don’t give up. The process will change the way you approach and solve problems.”

The Living Community Challenge, as an evolution of the Living Building Challenge, incorporates ecological restoration, conservation planning, and regenerative design towards restorative places beyond the scale of individual buildings and sites. In doing so, it provides an essential model to guide and prioritize whole-system thinking for a comprehensive cross-section of new and renovated communities. The LCC helps us all to better envision a way of creating and renovating neighborhoods as restorative tools for the health of people and the planet.