A marine biologist in the Caribbean wants to learn about a smartphone app for monitoring sea turtles that was created by a Kenyan conservation NGO. A software developer in the Netherlands is looking for bioacoustics researchers to critique a monitoring device he is building. A doctoral candidate in Germany is seeking affordable LiDAR scanners for forest surveys in Amazonia. A crowdfunding site for science-based research is soliciting proposals for projects using new technologies for environmental monitoring. A farmer researching silvopasture in the UK is looking for tips on sourcing the best camera traps for monitoring dung beetles.

If only there was a place where these users, manufacturers, and supporters of conservation technology could connect with one another. There is. It is called WILDLABS.

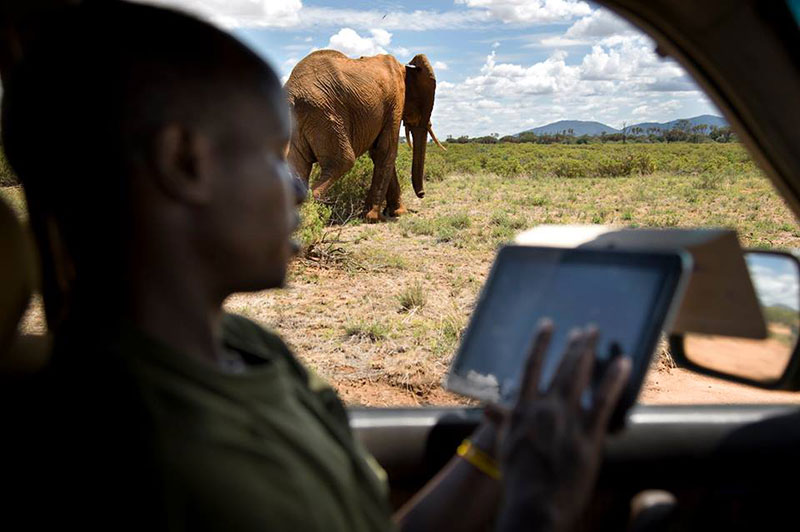

Save the Elephants, a member of the WILDLABS community, applies tracking technology that uses data from elephant collars ©Frank af Petersens, Save the Elephants

Launched in 2015 through a partnership involving some of the world’s leading nonprofit conservation organizations, WILDLABS is a global community that is helping to ensure that conservation efforts are benefiting fully from accessible, affordable, and effective modern technology innovations. In less than a decade, this community has expanded to include more than 7500 active members from 120 different countries. According to WILDLABS Research Lead, Talia Speaker, it has also become “the go-to place for all things conservation technology.”

Through WILDLABS, users, developers, and supporters of conservation technology can exchange ideas, crowdsource information, find collaborators, and share the impact of their work. In such a relatively new and rapidly evolving field, this kind of connection is not only vital for staying on top of the latest advances in tools and technologies, but also for enhancing our ability to monitor and protect an increasingly threatened natural world.

Researchers from Top Predator Alliance combine acoustic monitors with surface and underwater camera traps in Antarctica. ©A. Hasselmann, R. Eisert. @TPAonIce

According to Speaker, WILDLABS was initially created to provide a platform for connection, something that was lacking in the budding field of conservation technology. “Over the past eight years, we’ve grown this community, and it is the heart of everything we do,” said Speaker, “but we’ve evolved to become much more than an online platform.”

While continuing to nurture and connect the conservation tech community, WILDLABS also focuses on delivering programs that address the needs of its members. These needs constantly surface as technology advances, and WILDLABS uncovers them through surveys, focus groups, workshops, events, discussion forums, and informal conversations with community members. According to Speaker, they tend to cluster around three pillars: community, research, and resourcing, and it is around these three pillars that WILDLABS’ programming is structured.

Community

Much like other industry-specific organizations and platforms, WLDLABS fosters community by hosting and promoting live and virtual events, providing access to the latest and most relevant studies and articles, and sharing news about funding and job opportunities. A very popular WILDLABS community event is the annual, week-long #Tech4Wildlife Photo Challenge, which provides people with a platform to share their work and a literal glimpse into the world of conservation technology.

A #Tech4Wildlife Photo Challenge entry showing a biologger on a kākāpō (Strigops habroptilus) ©Dr. Andrew Digby

“Community is all about bringing people together and making information available, because that is one of the biggest barriers people face in this space.”

But where WILDLABS really facilitates powerful connections is through its groups, forums, and virtual meetups, where people can engage in conversations focused on just about any theme relevant to the field of conservation tech.

A WILDLABS and Satellite Applicationis Catapult event in Oxford, UK. ©Stephanie O’Donnell

For example, on their online platform, WILDLABS.NET, there are groups and discussions dedicated specifically to acoustic sensors, eDNA and genomics, wildlife crime, and building your own data logger. WILDLABS also produces webinars and publications that aim to bring to the fore new tools, technologies, and information in ways that are digestible and useful for end users.

Screenshot from a WILDLABS “Tech Tutors” presentation by Sean Sturley, Programme lead for Cyber Security at the University of the West of Scotland

“Community is all about bringing people together and making information available,” said Speaker, “because that is one of the biggest barriers people face in this space.”

A WILDLABS event in Kigali, Rwanda. ©Talia Speaker

One of the most exciting ways WILDLABS is bringing people together is through “The Inventory,” a community-curated living portal of all conservation tech tools, projects, and organizations—complete with reviews and a map showing connections (geographic, species, partners, etc.) between different efforts. The project aims to increase visibility and reduce duplication of efforts. The Inventory is currently open to beta users and WILDLABS is still seeking input from the community before its planned phased launch begins early next year.

Research

At the foundation of WILDLABS’ research programming pillar is its annual State of Conservation Technology study, which gauges the needs of their community, as well as the global pulse of conservation technology. It also identifies the tools and technologies the community perceives as most promising. In the most recently published State of Conservation Technology (Dec. 2021) those were identified as AI, networked sensors, and eDNA.

Speaker cites the massive reduction of time and manual labor previously devoted to data processing as the key appeal of AI. “For example,” she says, “out of thousands of images, AI can quickly pick out which ones contain a species of interest, or over hundreds of hours of acoustic recordings, which ones are the call of an endangered bird.”

©Ana Verahrami, Elephant Listening Project

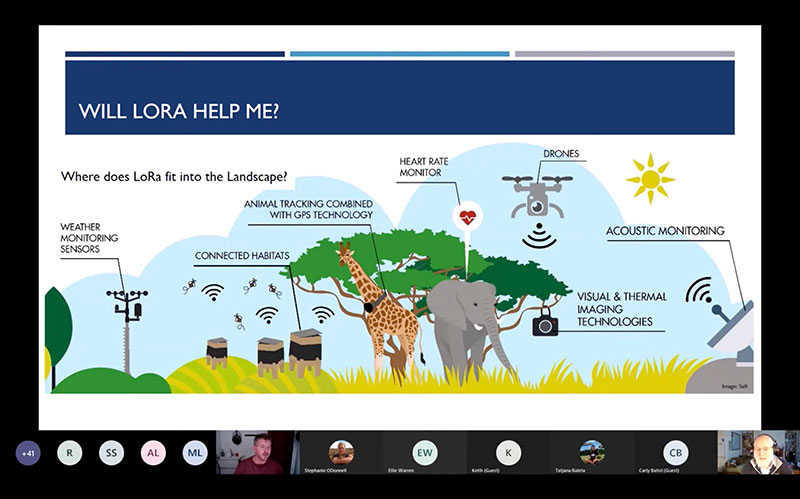

By leveraging the Internet of Things [the network of the billions of devices that are connected to the Internet, sharing, and collecting data], networked sensors help devices such as camera traps, acoustic recorders, and tracking devices become the live eyes and ears of conservationists. “Networked sensors have really high potential for real-time monitoring in situations where having timely action is important,” she says. Such situations can include poaching incidences, incursions into protected areas, or human wildlife conflicts.

Benjamin Barca (#Tech4Wildlife entry)

When it comes to eDNA, Speaker cites the appeal of a low cost technology that provides “big bang for your buck.” “By picking up samples of water or soil, for example, you can get information on tons of different species across a landscape,” she said. “This could be important for extending a protected area or understanding how to manage that species or seeing, for example, shifts in where that animal is located due to climate change or changed habitat conditions.” According to Speaker, community members also see eDNA as a high potential tool for capturing information on large landscapes where walking around and looking for animals or setting up a large number of camera traps is not realistic.

In collaboration with an electrical engineer and a master falconer, University of New Hampshire acoustic ecologist Laura Kloepper, Ph.D. uses a “biological drone,” a Harris hawk equipped with audio and video sensors to monitor bats @ProfLKloepper

WILDLABS recently conducted a three-year analysis of trends over time and while the findings have not yet been released, Speaker shared that AI and networked sensors remain among the three technologies regarded as having the most potential. Rounding out the top trio was not eDNA in this case, but rather animal-borne sensors used to monitor species’ movements and behaviors.

Computer scientists and engineers at the University of Washington have created a sensor package that is small enough to ride aboard a bumblebee ©Mark Stone, University of Washington

Changes in perception of a particular technology’s promise are not surprising. “It is helpful to keep in mind the technology hype cycle,” she warns, referencing the Gartner hype cycle. A framework for understanding how waves of interest in technology evolve over time, the Gartner hype cycle includes five phases: the Technology Trigger; the Peak of Inflated Expectation; the Trough of Disillusionment; the Slope of Enlightenment; and the Plateau of Productivity. “Basically, there’s this initial excitement and hype that often happens, and then the reality sets in,” she said. “Ultimately you get to a useful, productive place of, ‘Okay, how do we actually apply these tools?’”

According to Speaker, who leads the State of Conservation Technology research, the study provides a benchmark for progress, but also a mechanism for sharing back challenges and creating opportunities for strategic interventions that can bring more resources to community than WILDLABS could provide on its own.

Resources

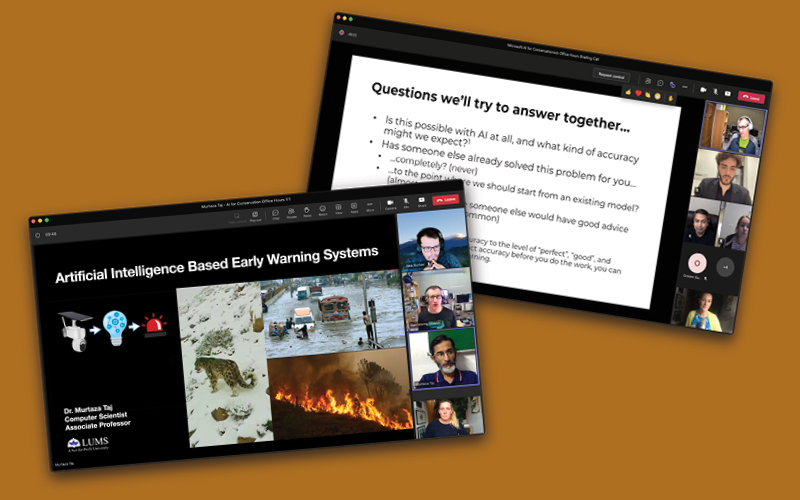

WILDLABS is highly focused on strategic, cross-sector partnerships that unlock access to funding, technology, knowledge, mentorship, and training. Take WILDLABS’ AI for Conservation Office Hours program, for example. Through this resource, conservationists who want to integrate artificial intelligence technologies into their workflows can access free, one-to-one virtual sessions with experts like Dan Morris, the former Principal Scientist for Microsoft’s AI for Earth program and the current Research Scientist with Google’s AI for Nature and Society Program.

WILDLABS Office Hours. Screenshots by Stephanie O’Donnell

In partnering with big tech, WILDLABS seeks more than funding and short-term demonstrations like hackathons and volunteer days. “Conservation projects really need dedicated engineering, financial support, and engagement to be effective,” said Speaker. With that in mind, and the goal of sustainably bridging the technology and conservation sectors, WILDLABS recently initiated a Fellowship and Awards program. Billed on the WILDLABS website as “Matchmaking between tech and conservation,” the program provides grant funding, industry expert mentorship, and community connection to support current and future conservation tech leaders. The program’s inaugural cohort of fellows is working with Edge Impulse, a Silicon Valley startup, to embed and use AI on camera traps and acoustic monitoring devices. Each fellow has a different focus, but they are both very interesting projects that probably wouldn’t have been able to happen without that combined expert mentorship and resourcing.

In partnership with Arm, WILDLABS will also be expanding these support systems in the form of awards. Later this year, the new program will launch 16 awards ranging from $10,000 to $60,000 to support conservation technology work within the community, with a roadmap developed to scale further in future years. (feel free to edit! This is adapted from our annual report, to be released soon.

When the 2021 State of Conservation Technology study showed that women in lower income and developing countries faced disproportionately high barriers to obtaining skills in conservation technology, WILDLABS responded by creating its Women in Conservation Technology program, which provides a cohort of women with technical training and professional development.

The 2023 Women in conservation technology cohort (Tanzania) ©Stephanie O’Donnell

For the program’s first year in 2022, WILDLABS partnered with Arm, Fauna & Flora International, and the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in central Kenya to provide 15 Kenyan women with training in the use of sensors and data processing tools; mentoring; and leadership skill building over a six-month period.

Dr. Meredith Palmer lion tracking in Kenya with the Women in Conservation Technology cohort. ©Talia Speaker

This year’s cohort, which is supported by a partnership with the Grumeti Fund, Fauna & Flora and Arm, is learning similar skills in Tanzania. WILDLABS will monitor participants to better understand how and if the program influences their careers and perspectives over time, but according to Speaker, feedback from the mentors, trainers, and participants in both cohorts has been extremely positive and the program has already generated a ripple effect.

WILDLABS’ Talia Speaker with Women in Conservation Technology participants ©Stephanie O’Donnell

Speaker says that some conservancies where the Women in Conservation Technology participants work have already replaced paper-based data collection methods with apps they have learned about through them.

Women in Conservation Technology participants , learning in the field. ©Stephanie O’Donnell

The Kenyan cohort organized an entire session on Gender Equality in Conservation at the 2022 Earth Ranger User conference. “It ended up being one of the most highly attended sessions and most watched YouTube recordings from their entire conference,” said Speaker.

Graduating cohort of the inaugural Women in Conservation Technology Programme: Kenya ©Stephanie O’Donnell

Members

So just who are members of the WILDLABS community? According to Speaker, the main sectors represented include wildlife conservation, which may range from someone with a large NGO to a field biologist to the manager of a small, protected area; research and academia; and technology, which includes people who do not work in conservation technology but want to contribute their skills. Speaker says WILDLABS is increasingly seeing engagement from government agencies, particularly from East African countries where they are running initiatives such as the Women in Conservation Technology program. “Our community includes everyone from wildlife enthusiasts who want to know what birds are in their backyard to hackers who just love building tools and want to do something good for the environment.”

Interdisciplinary collaboration is going to be the future.

Regardless of one’s interest in technology, WILDLABS is an ideal community for tomorrow’s conservationists, or anyone interested in a career shift towards conservation. “Whether you like it or not, technology is going to be part of your life and career,” Speaker said. “Interdisciplinary collaboration is going to be the future.”

A WILDLABS in person event in Cartagena, Colombia. ©Ted Schmitt

Is there a place for restoration practitioners in WILDLABS? Absolutely, according to Speaker. “The more diverse and interesting and different perspectives we have, the more interesting and useful innovations will come out of it,” she said. “Planners and designers bring so much, particularly when they really take the time to listen to the challenges being discussed in the community and co-develop tools or solutions with those on the front lines of conservation.”

From WILDLABS’ initial focus on wildlife and biodiversity conservation, the platform and community are growing to include issues at the intersection of biodiversity with other topics, such as environmental justice, agriculture, and climate change.

Ethics

Aware that the impacts of conservation technology may not always be positive, WILDLABS works to explore and address ethical issues through its discussions and programming. These include direct impacts, such as monitoring tools that are invasive or could affect an animal’s welfare, or the pollution generated when trackers are left in the field. There are also social impacts, like the “human bycatch” that can occur when surveillance technologies are deployed. Speaker related a story that was shared by researcher Trishant Simlai, during a recent WILDLABS panel discussion about the presence of camera traps and their cultural impact:

“In this particular community, women would collect firewood. That was the only time they could communicate with one another away from the men, and they often did this through singing. But when camera traps were placed in the areas where they collect firewood, they stopped singing.”

Speaker says that there has been growing attention to this topic, and some guidelines are beginning to come out of the community. She also acknowledges that more discussion is needed, and WILDLABS intends to foster that.

Connection

It would be impossible to quantify the conservation successes made possible by WILDLABS, but one anecdote helps illustrate the power of its network to make seemingly unfathomable connections.

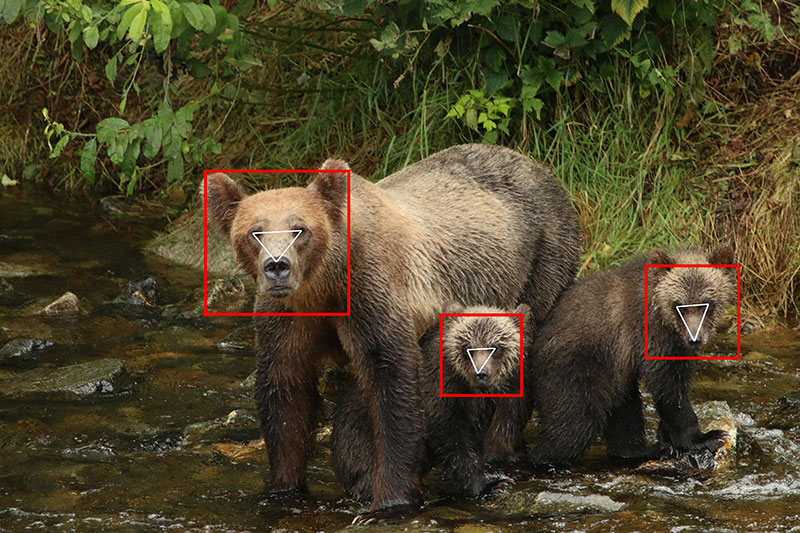

In 2014, a former ranger at Katmai National Park in Alaska noticed how popular the park’s new bear webcams had become and decided to do something fun: put on “Fat Bear Week,” a single-elimination-style competition where people could vote for the fattest park bear. The event became wildly popular on social media, catching the attention of hundreds of thousands of people. Among them were two software developers from Silicon Valley who had created Dog Hipsterizer, a smartphone app that could put moustaches and glasses on dogs. Wondering if the deep learning technology they used for the app might be applicable to individual brown bear identification, they joined WILDLABS to connect with the conservation tech community. On that very same day, a bear ecologist who was studying brown bears also joined WILDLABS. The WILDLABS team saw that both parties were interested in the use of AI to identify individual brown bears and connected them. That connection led to the creation of the BEARID Project, which is developing tools that can identify individual bears using facial recognition.

©BearID Project

As this story illustrates, cross-sector, interdisciplinary collaboration can open up possibilities never before imagined. It is shaping the future of conservation, and WILDLABS is committed to facilitating the connections that make it possible.

Note: WILDLABS is led by a Steering Committee comprised of representatives from a consortium of NGOS: Conservation International, Fauna & Flora International, Wildlife Conservation Society, and World Wildlife Fund. There are a number of ways to support WILDLABS growing network, including by joining it!