Non-Profit Spotlight: EcoHealth Alliance

By Amy Nelson

“What worries me the most is that we’re going to miss the next emerging disease, that we’re going to suddenly find a SARS virus that moves from one part of the planet to another, wiping out people as it moves along… that’s something to be keeping you awake at night.”

That was 17 years ago, when Scott Pelley and his 60 Minutes crew joined wildlife biologist Peter Daszak off the coast of the South China Sea on the island of Pulau Tioman. Dr. Daszak and his colleagues were looking for a species of pteropid bat (flying fox), the suspected source of the Nipah virus (NiV) in neighboring Malaysia. He explained to Pelley that “almost 75% of emerging diseases in humans actually come from wildlife or domestic animals… and we are looking for the next HIV, the next SARS” at the intersection of human health, veterinary science, and conservation biology. Daszak was there as part of the Consortium of Conservation Medicine, a partnership of Harvard, Tufts and Johns Hopkins University, the US Wildlife Health Center, and the Wildlife Trust.

Today, that partnership is known as the EcoHealth Alliance, and its members continue to track and try to prevent emerging diseases from spilling over into human populations, as we destroy and encroach into wildlife habitat with increasing frequency. They apply an interdisciplinary approach to strengthen systems globally and locally by recognizing that the health of humans, animals and the environment is interconnected. This approach, named “OneHealth” by Daszak’s colleague and EcoHealth Alliance Executive Vice President, Dr William Karesh, has gained traction with organizations like the World Health Organization, the UN, USAID and others.

According to the EcoHealth Alliance’s Samantha Maher, a conservation specialist with a background in wildlife conservation, environmental economics, and geography, the landscape itself plays a key role in the OneHealth approach. “We’re trying to figure out how we can configure landscapes such that we’re minimizing the impacts of disease while still maximizing the economic returns of the communities who live in these landscapes,” she said.

The EcoHealth Alliance is a multidisciplinary, nonprofit organization formed with the merger of the Wildlife Trust and the Consortium for Conservation Medicine in 2010, but they have been working on these issues since 1971, united in an understanding of the important linkage between emerging diseases and wildlife conservation. The early scientists coined the term “conservation medicine” and when SARS and Ebola first emerged as serious public health threats, the work took on new urgency.

Their model is unique. It is organized under the interlocking themes of Biosurveillance, Deforestation, OneHealth, Pandemic Prevention, and Wildlife Conservation. But they are a fairly small organization, with a full-time staff of only 27 individuals located in a small central hub in New York City. Those staff are then bolstered by small research and outreach hubs around the world, employing entirely local expertise and setting up community offices in cooperation with in-country universities, research institutes, and social service organizations. The NYC staff and leadership focuses on grant writing, data analysis, building lasting collaborative relationships, and sharing information with the international public health community. Maher explained that they are mainly supported through grant funding, primarily from USAID and with some support from NIH and a handful of private foundations including Packard, Ford, Johnson and Johnson, and the Gates Foundation.

And true to the OneHealth idea, they don’t just hire conservation biologists. Their team includes geographers, biodiversity experts, veterinarians, epidemiologists, economists, social and behavioral scientists, wildlife conservation specialists who run rehab facilities, and experts in the wildlife trade- all under one virtual roof.

Their approach is not just to track and understand the emergence of disease, but also to advocate for behavioral change and land use and policy decisions to try to minimize the most high-risk behaviors and circumstances. The organization does not, however, ask communities to compromise their traditional ways of life. They try instead to promote safer behavior and policies, which is one of the main reasons they rely so heavily on in-country expertise.

Maher notes that it is important, when asking people to change their behavior, to “…acknowledge that many of these communities have been interacting with wildlife for hundreds of thousands of years. And to tell them suddenly they can’t do that, it’s not helpful.” That’s why the EcoHealth Alliance doesn’t advocate for an outright ban on wildlife markets, the wildlife trade, or hunting. Instead, they focus on engagement and outreach within the local community to introduce behavioral changes that lower the risk of spillover but do not compromise the way they live. For example, the organization advises many communities not to plant mango trees in pig paddocks, where Dascak and his colleagues discovered, in 2003, that Nipah virus had spread to pigs that consumed partially eaten fruit dropped by bats, and then to the farmers of those pigs.

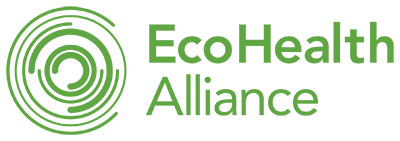

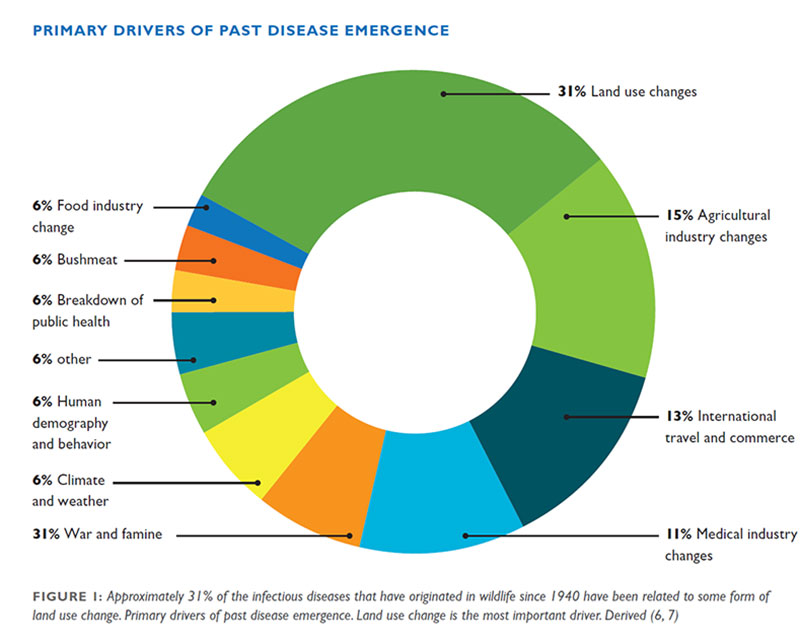

EcoHealth Alliance’s work is focused mainly in Southeast Asia, South Asia, West Africa, and parts of Central Asia – global hot spots of emerging disease. Narrowing those regions down to more specific locations took some clever scientific sleuthing. The EcoHealth Alliance focuses on instances of spillover from wildlife reserves into the human population, identifying the key variables at play in emergence: high levels of mammal diversity, high human population concentrations, and high levels of land use change (as a proxy for the level of interaction between humans and wildlife). What they found was an increased degree of interaction of humans and wildlife as those variables converged, with a higher risk of contact not only in the consumption of bushmeat, at wet markets, and in the illegal trade of wildlife, and but also in the growth of industrial agriculture and locations where human communities increasingly push deeper into native forest and clear it for development.

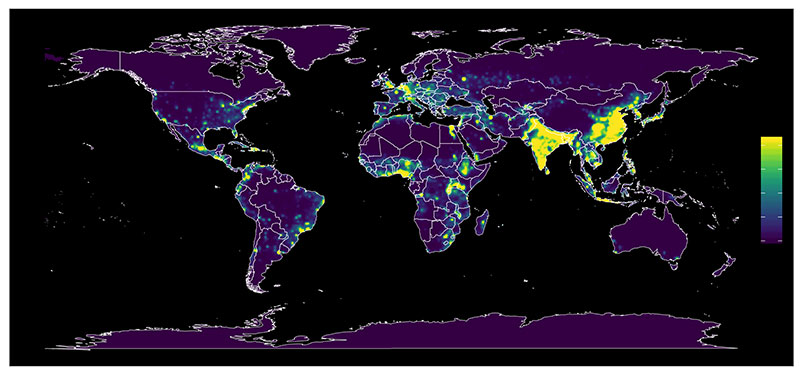

The EcoHealth Alliance focuses its in-country work on these locations, seeking to understand patterns and linkages and get a better sense of how to limit transmission and provide guidance for limiting exposure. A partial list of their current hubs includes: Liberia, Malaysia, China, Thailand, Indonesia, and more recently, the Pan-Amazon region. In Malaysia, their IDEEAL (Infectious Disease Emergence and Economics of Altered Landscapes) project examined the dynamics of malaria and palm oil plantations, specifically how different configurations of landscape and landcover were changing the rate of cases in Malaysian Borneo and direct impacts on health costs. They created an economic model that linked to a land use change model, to get to an optimal level of land conservation to minimize the cost of malaria.

This example highlights disease prevention as an important ecosystem service. It also illustrates the potential for practitioners of landscape architecture, planning, ecological restoration, and environmental engineering to collaborate with the EcoHealth Alliance and support the organization’s research at the intersection of land planning and disease prevention. Maher notes that there is so much more work to be done to build large databases of research and have more planners and policy makers use this data in decision-making and best practices for development.

As for other ways to support the work of the EcoHealth Alliance, Maher mentions the power of consumer choices to drive changes. By avoiding products with palm oil or reducing meat consumption, for example, people can impact the global supply chain that can drive habitat destruction, even as they sit sequestered at home.

Just last month, Dr. Peter Daszak was featured on 60 Minutes again, this time describing the work the EcoHealth Alliance had been doing to develop a vaccine for COVID-19 while having to defend against false narratives being circulated as the virus became increasingly politicized. The EcoHealth Alliance had been collaborating with the Wuhan Institute of Virology for 15 years, together cataloguing hundreds of other bat viruses – research critical to developing treatment protocols for COVID-19. But in mid-May this pivotal scientific collaboration was blocked when NIH cancelled their grant (one, it should be noted, that funded much more than just the research being done in Wuhan), based on a political disinformation campaign targeting the Institute.

Maher notes that when it comes to COVID-19 and other emerging diseases, at the core “this isn’t about pointing fingers at a country… We are not interested in villainizing people.” Because most of the time people in communities around the world are doing the same thing they have been doing for generations, while our populations grow, land use patterns change, and our global connections increase. She explains that the important thing to remember is that people learn and change behaviors and respond “when they are given the opportunity to, not when they are villainized for it.” The EcoHealth Alliance seeks to supply alternatives that still maintain important cultural structures and practices in that community, and preserve a sense of dignity.

Their ‘Living Safely with Bats” community outreach campaign is one such example of messaging within a potential spillover community by focusing on ways to change certain daily practices to minimize exposure. The campaign’s booklet was translated into several local languages and illustrated by one of the local EcoHealthAlliance scientists. The messaging was carefully developed to be for and about the community members, it’s language and illustrations reflective of the community it is trying to reach.

It is clear that the EcoHealth Alliance’s work, from tracking emerging diseases, to understanding wildlife and human behavior and examining land use change and economic impacts, is all about maximizing wellbeing and promoting a truly holistic approach to health.