Chicago: Ecology in Urban Planning at the Regional Scale

By Guest Contributor

By David Yocca, FASLA, RLA, Senior Landscape Architect/Ecological Planner

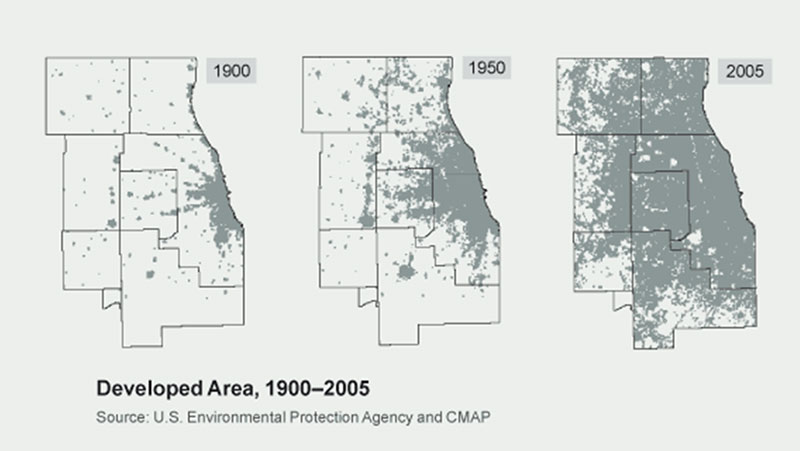

The Chicago area is known for many things, one of which is a legacy of bold, regional-scale planning that connects people to the lakefront, rivers and streams, and an expansive network of preserved natural areas. Connection to nature in one of the nation’s largest and most populated urban regions has engendered an awareness of and love for the unique and beautiful landscapes of Chicagoland for generations. Conservation plans, programs, and initiatives have and continue to be effective in collectively informing over a century of ecologically grounded planning in the seven-county area, the City of Chicago, and many of the municipalities within the region.

Ecological History

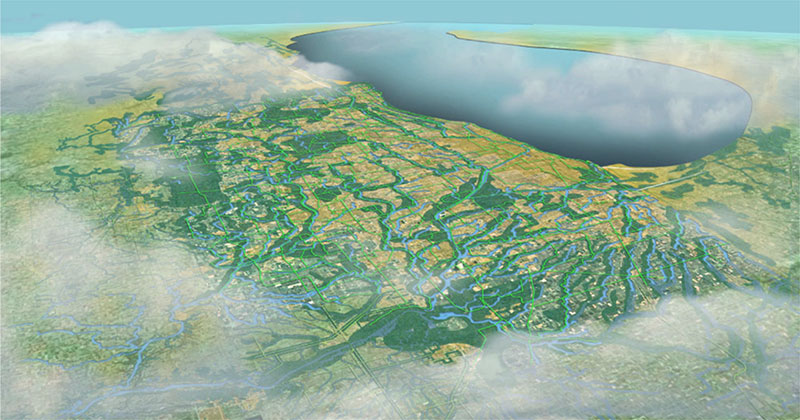

The prairies, savannas, woodlands, and wetlands of the Chicago region emerged during the Holocene following the retreat of the last glacier about 12,000 years ago. The geology and topography were formed by glaciers and subsequent meltwaters, and the landscapes co-evolved with the indigenous people that inhabited the area during that time. The native populations developed practices of harvesting timber, annual fire, farming, and gathering a broad array of perennial grasses and flowering forbs for baskets, medicines, dyes, and other uses seasonally. These practices helped sustain the biodiversity and resilience of landscapes that in turn provided food, shelter, warmth, and safety. In other words, indigenous people met their daily needs as an integrated and essential part of these complex ecological systems.

Following western settlement and the invention of the steel plow, the land was drained and managed for commodity agriculture and a growing population, although pockets of remnant landscapes remained that were either too difficult to drain, unproductive, or impractical to develop for other reasons. These remnant natural resources have formed much of the framework for the open spaces preserved from development for public benefit. Knowledge of aboriginal practices and their essential function in maintaining the habitat to which the native flora (and other organisms) originally adapted has been critical in the restoration and ongoing stewardship of the growing network of natural areas in the region.

The few remaining fragments of unmodified remnant terrestrial and aquatic landscapes not only give a glimpse of the past but help illustrate how important the natural ecology of the region is to flood attenuation, air quality, agriculture, biodiversity, and a host of other ecosystem services. The deep fibrous root systems of native grasses are this biome’s natural tool to sequester carbon, form and maintain organic content of rich, productive soil, infiltrate rainwater, and moderate the ground temperature. The importance of these systems for biodiversity and wildlife has been documented by many, including Dr. Gerould Wilhelm, co-author of the Flora of the Chicago Region and co-creator of the Floristic Quality Assessment methodology now used widely to assess ecological health and native landscapes in the region and throughout North America. Healthy, diverse native prairies, woodlands and wetlands attract and sustain a much more diverse and conservative array of birds, butterflies, pollinators, and other beneficial insects, as well as larger fauna.

Planning History

Land use and transportation patterns are also a legacy of the native inhabitants of the Chicagoland region. Major roads and highways follow original trade routes, and early recorded history from the 1700s describes Potawatomi women who were successfully cultivating grain crops to sustain their families and trading surplus to traders, missionaries, and military facilities. The region grew dramatically as the most logical transportation and trading hub to transfer commodities (meat, grain, timber and other construction and manufacturing materials) to Eastern cities where local sources had become largely depleted.

A timeline of ecological milestones underscores the relationship between detailed knowledge of the unique attributes of the Region’s ecology and regional plans and policies. The first citywide plan was written primarily to foster economically beneficial development and anticipate appropriately scaled infrastructure. However, the 1909 Plan of Chicago, widely known as the Burnham Plan for its lead author, contains several items that were environmentally innovative for the time, including the use of the entire lakefront for public use and enjoyment in perpetuity. The plan also lays out a series of parks and boulevards to ensure close access to green space for citizens, including natural areas that were already in the process of being secured, eventually becoming Cook County’s Forest Preserve system.

In 1913 the Illinois Forest Preserve District Act was created, largely due to the efforts of landscape architect Jens Jensen and architect Dwight Perkins, Prairie School collaborators who both believed there was a direct correlation between Chicago’s high levels of crime, disease, and premature death and the disconnection from nature resulting from urban conditions. They were passionate about the importance of making art, beauty, and natural landscapes accessible in public parks and reserves to Chicagoans of all socio-economic levels.

Immediately following, in 1914, the first forest preserve district in the nation was formally established in Cook County with a mission “to acquire, restore and manage lands for the purpose of protecting and preserving public open space with its natural wonders, significant prairies, forests, wetlands, rivers, streams, and other landscapes with all of its associated wildlife, in a natural state for the education, pleasure and recreation of the public now and in the future.” This soon led to the creation of county forest preserve districts throughout Illinois, including the other six Chicagoland region counties, each of which has identified, acquired, and preserved substantial areas of natural lands.

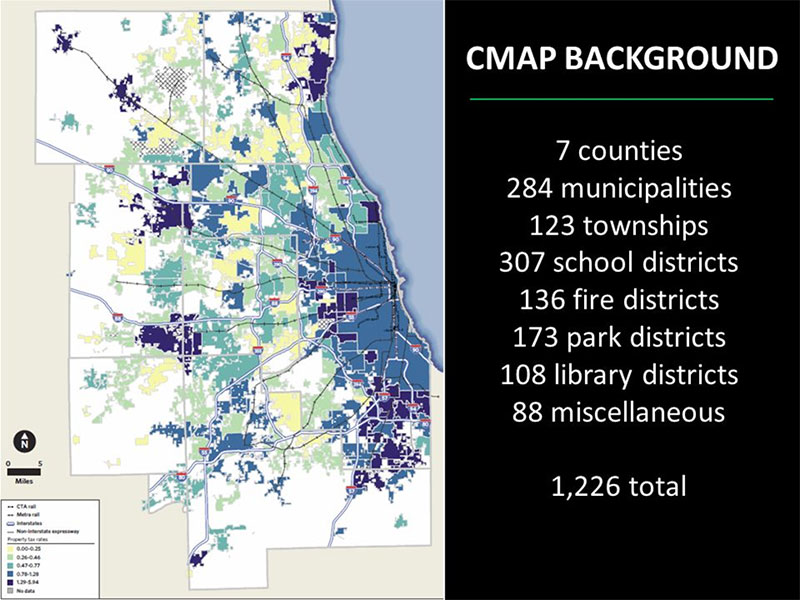

While each county, and each municipality within them, is responsible for their own land use and transportation planning, three key organizations have evolved, supported by dozens of others, to help coordinate these efforts on a regional scale: Openlands, Chicago Wilderness, and CMAP (the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning).

Openlands

One of the oldest metropolitan conservation organizations in the nation, Openlands is dedicated to “connecting the people of the Chicago region to nature where they live.” Since its founding in 1963, Openlands has helped protect over 55,000 acres of land for public parks and forest preserves, wildlife refuges, land and water greenway corridors, urban farms, and community gardens. Openlands has also helped promote the deployment of restorative, nature-based solutions to address climate change, local resiliency, and support connection to nature.

In addition to providing critical support for regional-scale ecological planning, land acquisition, restoration, and stewardship, they have developed and operate a number of innovative programs addressing healthy local food, environmental education/healthy school environments, outdoor recreation, and urban tree canopy.

Chicago Wilderness

In 1996, a coalition of like-minded conservation groups, businesses, foundations, and resource agencies formed Chicago Wilderness, “a regional alliance leading strategy to preserve, improve, and expand nature and quality of life.” Now with over 250 member organizations, Chicago Wilderness promotes the ongoing aggregation, preservation, and stewardship of natural lands and waters within the seven-county Chicagoland region. Chicago Wilderness has been a critical resource and voice to help educate the public about the benefits of embracing the region’s ecology in plans and policies.

Chicago Wilderness has been instrumental in helping people see and understand the immensely diverse nature and beauty of the region’s natural landscapes through breathtaking photography, trail maps of public preserves, and a popular awards program that celebrates people whose work best exemplifies inspiring conservation design, restoration, education and advocacy.

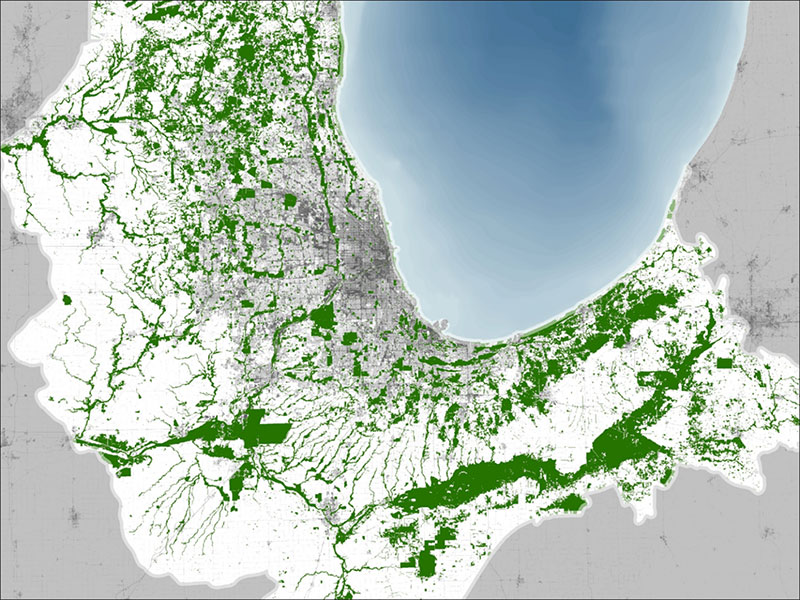

Chicago Wilderness also helps compile and make available detailed natural features data to support ecological planning, policy development and the creation of regional green infrastructure networks. In this case, green infrastructure is defined as “the interconnected network of land and water that supports biodiversity and provides habitat for diverse communities of native flora and fauna at the regional scale.” The Chicago Wilderness Green Infrastructure Vision (GIV) was developed through a collaborative, consensus-based process. It consists of spatial data and policies describing the region’s most important areas to protect. The first version was completed in 2004 and is now housed and refined in-house by CMAP with the help of The Conservation Fund.

Regional Green Infrastructure Network for the entire region, based upon existing land use, public ownership, municipal comprehensive plan policies, and many other GIS data layers. Courtesy of CMAP

CMAP

Chicagoland’s regional planning authority, the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP), was formed in 2005 through merging the Chicago Area Transportation Study and the Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission.

CMAP provides the municipalities and agencies of the region with a wide range of planning and policy support, including the creation and update of the region’s official comprehensive land use and transportation plan. The goals of the latest version, ON TO 2050, adopted in October 2018, are based upon three interrelated principles: Inclusive Growth, Resilience, and Prioritized Investment. The regional green infrastructure (GIV, as described above), is an essential strategy to help support all three of these principles in many ways.

In addition to the promotion of policies to support the ongoing preservation and restoration of the GIV, CMAP provides a range of site-scale green infrastructure policy resources to help realize the ability of green infrastructure to manage stormwater, improve urban ecology, and reconnect people to nature. The natural landscapes endemic to Chicagoland offer valuable insight to planners and designers striving to replicate natural hydrology and promote biodiversity in the retrofit of the region’s urban, suburban, and agricultural/rural landscapes. By combining strategically located natural area restoration with locally calibrated green infrastructure, these essential functions can be restored over time.

In support of the ON TO 2050’s Resilience principle, CMAP recognizes the critical need for the climate adaptation advantages that can accrue through their GIV and site-scale green infrastructure practices- “To remain strong, metropolitan Chicago requires communities, infrastructure, and systems that can thrive in the face of future economic, fiscal, and environmental uncertainties.” A healthy, diverse regional ecology is clearly more resilient to changing temperatures, rainfall patterns, and other weather-related impacts to the urban, suburban, and rural land uses. Site-scale green infrastructure supports reduced fossil fuel use, addressing urban heat island, improved water and air quality, provision of locally sourced fresh food, and a plethora of other benefits.

Green infrastructure ON TO 2050’s Environment chapter strongly encourages the region’s municipalities to embrace the use of green infrastructure. CMAP has developed many resources to support these practices, and offers technical assistance to help deploy them:

- Integrating Green Infrastructure. This ON TO 2050 strategy paper describes policies CMAP and partners can pursue to protect ecological cores, encourage green infrastructure in community-scale green spaces, green hardscapes, and account for co-benefits.

- Center for Neighborhood Technology Green Values Calculator. Estimates the environmental benefits and monetary savings associated with various deployments of bioswales, tree plantings, native landscaping, and other kinds of stormwater green infrastructure.

- Recommendations to the Illinois General Assembly. The University of Illinois at Chicago, CMAP, and several other organizations completed a report to the Illinois legislature recommending ways to incorporate green infrastructure into state regulations.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Provides information on the ways U.S. EPA is incorporating green infrastructure in a number of different agency programs, both regulatory and non-regulatory.

With its long history of ecologically grounded regional planning, the Chicagoland area is a true leader in natural resource protection, ecological landscape restoration and stewardship. Environmentally driven people, foundations, agencies, and private enterprises have collectively supported and realized hundreds of demonstrations and applications that have propelled a wide array of nature-based approaches from obscurity to mainstream. The region’s initiatives continue to foster some of the nation’s leading innovative applications of restorative practices that serve to reconnect citizens to locally authentic, healthy nature while protecting and restoring irreplaceable natural resources for future generations.

Additional references, articles, and resources can be found in the Resources section of Leaf Litter.