Dr. Larry Susskind ©CBI

Larry Susskind is Ford Professor of Urban and Environmental Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the Founder and Chief Knowledge Officer of the non-profit Consensus Building Institute, which provides mediation services in complicated resource management disputes around the world. He advises leaders and stakeholders on the resolution of land use conflicts, facility siting controversies, public policy disagreements, and confrontations over water. He has helped facilitate negotiations on arrangements of global environmental treaties. He offers a range of executive training programs each year and has served as guest lecturer at more than twenty-five universities around the world. Susskind has served on the faculty of MIT for more than 45 years. He also heads the MIT-Harvard Public Disputes Program. Susskind’s research interests focus on the theory and practice of negotiation and dispute resolution, the practice of public engagement in local decision-making, entrepreneurial negotiation, global environmental treaty-making, the resolution of science-intensive policy disputes, renewable energy policy, climate change adaptation, socially-responsible real estate development and the land claims of Indigenous Peoples. He is currently Director of the MIT Science Impact Collaborative, Director of the MIT-UTM Malaysia Sustainable Cities Program and Co-director of the Water Diplomacy Workshop.

You were educated as an urban planner. How did you get into environmental conflict resolution?

Anyone working on any kind of city development, city design, or regional planning activity must consider the natural environment within which development happens. As I started to work on issues of “what should go where,” which was a typical land use planning task in the late 1960s and early 1970s, it became clear that what went where did not just have to satisfy various community, city, or regional stakeholders; it also had to address the fact that natural systems needed to survive as they interacted with the results of political decision-making by government. Environmental planning is central to city planning and has always been central to my work.

What was a bit special about my planning work was that when we attempted to engage stakeholders in decisions about how to use natural resources or how development should proceed (given its likely impact on natural resources), people were invited to express their views. Not only did they disagree because their political interests were different, they also disagreed because they identified differently with the natural environment. So, there were political disagreements and science-based differences at the heart of most efforts to make development decisions. We had to find some way of reconciling these conflicting interests, or nothing could happen.

Dr. Larry Susskind instructing MIT Urban Studies and Planning students. ©Takeo Kuwabara/MIT Department of Urba Studies and Planning

Addition to teaching at MIT, I’ve been associated with Harvard Law School for many years. I know that going to court turns out to be a pretty bad way to resolve disagreements about the possible impacts of development on ecosystem services. Courts have zero ability to make a technically informed judgments. The judge or the jury interprets the scientific debate, but their goal is to say who is right and who is wrong in legal terms, not to correct technical mistakes. They certainly don’t accord any “rights” to the natural environment.

We needed to invent new ways of bringing multiple parties together and resolving science-intensive policy disputes. That led to the invention of what’s now called “environmental dispute resolution,” or “environmental conflict resolution.” This is an activity that is independent of planning. Planners tend to be knowledgeable about it, and in some cases involved in it, but lots of planning happens without environmental dispute resolution. EDR has taken on a life of its own over the past three or four decades, and it is now a fully formed professional activity, usually facilitated by professional mediators.

The short answer to your question is, then, I couldn’t do the work I wanted to do as a planner without figuring out a new and better way of involving people in making collective decisions that affect them, even when they disagree.

“… when people get together because they disagree about a particular natural resource management or development decision, political stalemate is not an acceptable option.”

Speaking of different groups disagreeing… is it harder to resolve environmental conflicts today than it was five or ten years ago, given the increase in political polarization and the divisive vibe that seems to be permeating discourse here in the US and in many other countries? Are people digging their heels in deeper now than they were just a few years ago?

That’s certainly an appropriate question, but I’m guessing you’ll find my answer surprising. It’s not any harder now than it was before. It’s the same. The reason is, when people get together because they disagree about a particular natural resource management or development decision, political stalemate is not an acceptable option. For example, if there’s a drought but somebody wants to develop their land, they are likely to say, “It doesn’t matter if there’s no water right now. We’ll find some.” And other people will say, “No. There’s a limited amount of water. We don’t want any more development in this area until and unless there’s a change in the availability of water.” It doesn’t matter whether you’re blue or red, your life in that place with regard to water availability and new development needs to be resolved. I’m not saying it’s easy, but people don’t usually reference larger political slogans when they are facing a site specific decision. With development, decisions are driven by a 30, 60, or 90-day permit review process. There will be a decision by the end of that time. The decision might be to go to court, but there will be a decision. Larger political questions won’t be resolved. They won’t even be addressed. No, I don’t think it’s harder to resolve environmental disputes in our highly polarized political environment. It was difficult before, and it’s difficult now. You just have to know how to proceed.

People discover that they need to put aside their larger political concerns when they come into the room to resolve an environmental dispute where they live and work. That don’t have to reach agreement on underlying values on or principles.

In a way, that’s a hopeful perspective: that even amid increased extremism, the urgency of a situation may result in more cooperation and compromise than one would think.

As long as you can make the point that they won’t be resolving the larger underlying conflict. Israel and Jordan have a peace treaty, for example, which allows them to share water. There’s strong hostility between the people on both sides of the border with regard to broader questions of what’s happening in the Middle East, but they can still agree to share water.

I’d like to think that the fight on the broader political battle becomes less ad hominem when parties work together on smaller operational issues. Maybe they even become more reasonable once they work together on something (anything!). I think it reduces the level of what’s called “the demonization of the other.” Demonization is easy when you never sit with, talk to, eat a meal with, learn anything from, or find out anything about the families of people you are dealing with on the other side of the table. If people work together on a continuing basis regarding what to do about the management of a shared natural resource–a forest, lake, or stream–and they get something worked out, when they go back to fighting about larger political issues, it’s a little harder to hold on to hostile assumptions and simple generalizations about the other side.

[Note: There is an emerging field known as environmental peacemaking/peacebuilding, which views environmental conflict and transboundary efforts to jointly manage shared resources as a foundation for peace, More about this topic can be found in the Resources section of Leaf Litter.]

Let’s talk about how some of those problems can get resolved. I understand that the not-for-profit Consensus Building Institute (CBI) , that you created, uses something called the Mutual Gains Approach. Can you tell me about that?

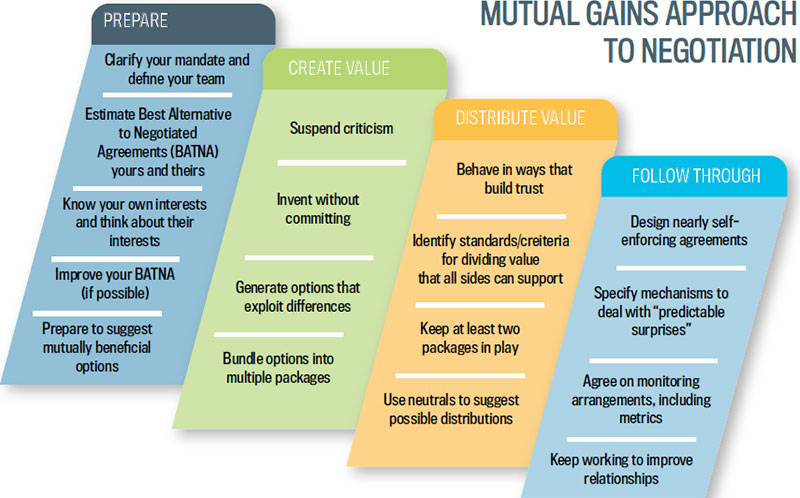

The Mutual Gains Approach was developed by CBI and the Public Disputes Program at Harvard Law School. It’s very simple. We think about conflict management as a four stage process.

The Mutual Gains Approach says that the first step in dealing with a conflict is the preparation the parties do before they sit down together. And, if there is a mediator involved, that person will talk to all the parties privately and prepare something called a stakeholder assessment. If a mayor says, for example, “This dispute has been dragging on forever! The pollution in this river has got to be addressed. Every time we try to do it, somebody doesn’t like the approach we propose. We’re going to hire a neutral organization like CBI and work something out.” The first thing CBI says is, “We have to talk privately and without attribution to all of the key stakeholders.”

There is always an obvious first round of stakeholders. Everyone knows who they are. They are the ones who have been standing up and yelling, filing lawsuits, and being visible in the media. When we talk with those people privately, off the record, we ask, “Who do you think needs to be at the table?” The first round of stakeholders usually suggests a second circle of people. Then, whoever is sponsoring this process–an elected official, a not-for-profit, a neighborhood foundation, a state government–makes a public announcement that mediators are engaged trying to understand everybody’s view on the issue. The announcement includes a number anyone can call to be in touch with the mediator. A lot of people who call are surprised to find the mediator has already spoken with the head of their organization.

We listen to what everyone has to say about the situation and produce a map of the conflict. Think of a simple matrix. Down the side are stakeholder categories of stakeholders, and across the top are issues that they raised, which we summarized into the smallest number of most pressing issues possible. What does that category of people have to say about that issue? How important is it to them, and what would they like to see happen and why? What would they not want to see happen? What information do they wish they had? We then send our draft matrix (without quoting anyone directly) to everybody we talked to. We ask, “Is there anything you think you told us that’s missing from this matrix? If so, let us know, and we’ll fix it.”

With the completed matrix in hand, we can write a brief description of what we think a good process would be for the group to follow. We can spell out an agenda, a timetable and possibly a budget. The selection of specific participants would be up to the various stakeholder categories. They will have to meet and pick someone.

Then we send our proposed process design to everybody we interviewed, and ask, “If this were the process, would you participate? If you have a problem with it, tell us, we can try to make an adjustment.” When we’ve finished that cycle, we hand that proposed process, along with the list of groups that should be invited to convene and choose representatives, the budget, and a description of any technical support the group will need, to the convener and say, “If you proceed in this way, you’ll have everyone’s support.” That’s what we mean by preparation for an environmental dispute resolution effort. That’s the first step in the mutual gains approach. And you could do this at any scale. We have even applied it to global environmental treaty negotiations.

The next step in the mutual gains process is what we call the “creation of value.” You bring the parties together and the first set of things you do are aimed at finding ways of adding issues, reframing issues, and exploring possible trades. All of this aims at the question, “If the group meets your most important interests in a certain way, would you be willing to meet the other interests as they request?” Everyone knows everyone’s interests, of course, because they have the matrix in front of them. This allows them to engage in problem solving or value creation. That’s the second stage.

At some point the parties say, “Okay. That’s all the value creating we can do. We now have to reach an agreement, and not everybody is going to get everything they want. How shall we distribute the value we’ve created? What’s the detailed, implementable plan we can agree upon that meets every parties’ most important concern?” Given that we have at least a representative of every group that needs to be there, we say, “Let’s produce a detailed agreement in writing.” We then have everyone who has been working around the table take that draft agreement back to the group they represent, discuss it, and come back for a final meeting. A little more discussion may be necessary, but at that point what we are hoping to hear is, “My people say that if that’s the agreement, and as long as everybody sticks to it, we can live with it.”

©Professor Lawrence Susskind at MIT and the Consensus Building Institute (CBI).

We then take that draft agreement, put it in final form, have all the groups acknowledge that they will live by that agreement. The product is then turned over to whichever of the participating stakeholders has the authority to implement the agreement. That could be a government agency, or multiple agencies, or a private actor.

The last step in the Mutual Gains Approach is follow through. We need to build into the agreement what the process will be for monitoring everyone’s performance and resolving any disputes that arise. The dispute resolution effort is not over until all the commitments have been fulfilled.

The mutual gains approach is well documented. You can see a lot of detailed case reports in The Consensus Building Handbook (Sage, 1999). The Consensus Building Institute website has information and dozens of case studies of the use of the Mutual Gains Approach to resolve environmental conflicts.

Neutrality seems critical to this process. Many of our readers may be involved in projects where this step is not in the budget or scope of work, or where a client’s interpretation of stakeholder engagement is to simply to hold a public meeting. What are the options for practitioners who really want to engage people in the decisions that will impact them in their community, but don’t have the resources to bring in a professional mediator?

Establishing one’s neutrality is not easy. Training and certification help. Without a professional neutral it’s highly unlikely that an environmental conflict resolution effort will succeed. Parties say they don’t have money for lawsuits, but then they find themselves paying for legal advice over an extended period. The cost of mediation can be split among the parties. It can be covered by one “side” in a dispute as long as that part hands over the money to support the mediator to a small executive committee appointed by all the parties, and the agency or actor who provided the funds gives up control over them. The mediator needs to work for the full group.

Dr. Larry Susskind instructing MIT Urban Studies and Planning students. ©Takeo Kuwabara/MIT Department of Urba Studies and Planning

What would you recommend for practitioners who do want to find a professional neutral mediator? What’s the best resource? Is there a particular association?

The U.S. Congress created the United States Institute for Environmental Conflict Resolution decades ago, and the hundreds of people who have done the most environmental mediation in America are listed on their roster of professional neutrals. Say you want to know who the environmental party or the city agency was when a particular mediator worked on a water in Arizona. You can find out on the USIECR website. There are many groups like CBI around the country.

[Note: The U.S. Institute for Environmental Conflict Resolution is now known as the Udall Foundation’s John S. McCain III National Center for Environmental Conflict Resolution. An interview with the National Center’s Director, Brian Manwaring, is featured in this issue of Leaf Litter.]

In addition to not having a neutral party to mediate, what are some of the key barriers to conflict resolution?

Obviously certain individuals can be barriers. If we are talking about a very large-scale development project, and the project sponsor or developer says, “We think we have the right to do this, and we’re happy to go to court. We’re not participating in any conversations with anybody,” then mediation is impossible. It’s not possible to reach agreement if you have a protagonist who won’t participate.

Getting the parties to the table requires people who know how to do that. As mediators, we know how (in a private conversation) to show each party in a dispute why and how it will be in their interest to at least come to the table at the outset. Once they’re at the table, I’m not worried about how severe the conflict is, or how stuck they are because of what has happened in the past. If they’re there, there are ways of shifting and reframing the conversation so that joint problem solving becomes possible. My book Good for You, Great for Me: Finding the Trading Zone and Winning at Win-Win Negotiation is a good source of information about this process. It is not written for professional mediators; rather, it is for potential parties.

Many of our readers work on projects in urban communities that are facing serious economic and social justice challenges. What advice do you have for planners, scientists, designers who are working on projects like this, but don’t have expertise with issues like economics, public safety, and legacy racism? Would you say those are situations where you need a mediator to come in, find those experts, and involve them in the process?

Yes. In many of the situations you describe, what they need is “joint fact finding.” For example, if you’re trying to prepare a water management plan, or some kind of restoration plan for a site, what you don’t want is everybody thinking they should get their own expert. Then, all of those experts disagree because their approach is driven by what each of the different groups has asked them to do. Someone who says, “I’m really a neutral expert. You don’t have to listen to all those other people,” isn’t going to get anywhere. The question is how to construct a process of joint inquiry with regard to scientific and technical aspects of a dispute, and that is something that happens inside of environmental conflict resolution. There is an established method to do it in a collaborative way. My colleague and former doctoral student, Todd Schenk, who is a professor at Virginia Tech, wrote a wonderful new book about joint fact finding with lots of locally oriented case studies, many of which are about air and water.

The problem you describe in your question is not really about environmental mediation. It’s not about the importance of neutrality of the mediator selected to run the process. It’s about having an idea of what it takes to generate collaborative answers to scientific or technical questions that can feed into a public decision process. When we are dealing with science-intensive policy disputes, we need a way to inject technical analysis into a collaborative problem-solving process.

Watershed work crosses so many political boundaries. Collaborative water management at the scale needed to make meaningful change in terms of water quality, flood control, fire management, ecological health, is often outside the scope of individual groups or municipalities. What are some formal agreements that have effectively gained commitment from a vast group of participants in collaborative water management?

Most of these are from California. There’s a wonderful book by Judith Ines and David Booher, Planning with Complexity: An Introduction to Collaborative Rationality for Public Policy (Routledge). It’s all about the Cal Fed process. That was the most extensive collaborative process across water in Northern and Southern California, and it worked very well. It was facilitated by the state mediation office, and it’s the best U.S. story of broad scale facilitation of water systems management.

My book, Water Diplomacy: A Negotiated Approach to Managing Complex Water Networks (Routledge) presents the Water Diplomacy Framework, which I developed with my colleague, Professor Shafiqul Islam. It basically says that if you treat water management and water planning as a zero sum problem, you are doomed to irreconcilable conflict. But if you understand how to “create more water”, that is, recycle, reuse and increase infrastructure efficiency, then you can switch the focus of the discussion. When I think about the Nile, and think about talking to Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt, I say, “You need to create more water.” They would probably say, “That’s not possible. There is going to be less water, not more water.” And I would say, “I know how to double your water immediately, and I’m not talking about desalination. Just find a way to re-use all the water in the Nile a second time. You have to invest in infrastructure. You do not have to let all the water you’re using in agriculture go out into the sea. It can be reused. You can take all the water from the city and reuse it.” They fight about who gets how much of the Nile, but they don’t think about how they can, through collaborative efforts, increase everybody’s water security by creating more water through jointly managed reuse, conservation, and investment in infrastructure.

In most water disputes, the focus is only on who gets how much water. And that’s been the problem. The approach called “integrated water resource management,” which we criticize in Water Diplomacy, is focusing on the wrong thing. They’re talking about who gets how much. The issue is how to jointly decide what they can do to create more water. To reuse the water that is naturally occurring in ways that serve multiple interests.

What’s the key to shifting mindsets to look at the issue that way?

I think getting everyone to listen to the views of all the other stakeholders is the way to start. When you hear everybody talking in zero sum terms, you can hold a mirror up and say, “You guys aren’t talking about multiple use, reuse, and what you can do to meet everybody’s interest. Let’s have a process of collaborative work here, with help from a neutral party who can assist you in doing that.” They don’t say no. They don’t say, “We don’t want to hear that.” They just need someone to open that window for them.

Many of our readers work on projects in coastal communities. You co-authored the book Managing Climate Risks in Coastal Communities: Readiness, Engagement and Adaptation (Anthem Press), which tells the story of how four New England coastal communities attempted to collectively assess local climate change risks using a simple, but tailored, one-hour game. Can you talk about your use of role-playing (serious games) in environmental conflict resolution?

We found that by playing a one-hour game, people’s sense of what a facilitated or mediated process could produce in their community changed.

If you go to localclimatechange.mit.edu, you can see the four case studies that led to the games. You can also see the links to the evaluation of how the games changed people’s thinking. I’ve written multiple short pieces about this on my blog. I also wrote a piece called Can Games Change the Course of History? Nature has published our work in assessing (statistically) the impact of role-play simulations on community groups that are unable to imagine working together (Role-play simulations for climate change adaptation and education engagement.)

The key is to involve people face-to-face in a game in which they don’t play themselves, but rather a recognizable counterpart in the situation they’re in. The game needs to be tailored to that situation, and it must seem realistic so that as people work to try to resolve a problem, they’re learning the real data and they are seeing what could work in their community. When they can reach agreement in the game, they say, “Well, jeez, we could do that in our own situation.” And because they don’t play their own role, they’re not giving anything away in the political debate that will follow when they engage in mediated problem-solving.

A small group engaged in role-play with CBI staff ©CBI

There’s a large body of work studying the effects of games, gaming, and role-play simulation. The Program on Negotiation has something called the Teaching Negotiation Resource Center, which has over 200 games and teaching exercises. And you can search by terms such as water, or by regions, such as Southwest. Games can make a very big difference at every scale.