Book Review: A Wild Idea

Ted Brown, PE

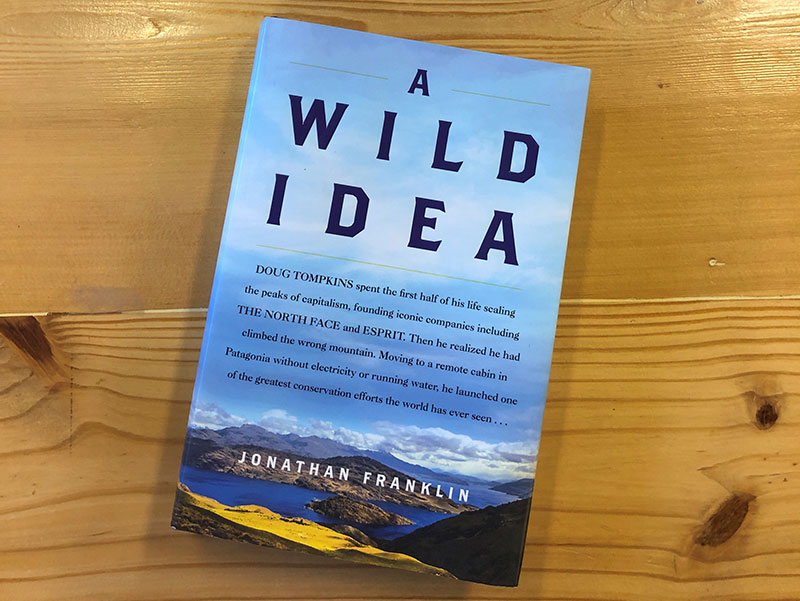

In his book A Wild Idea, Jonathan Franklin tells the remarkable story of Doug Tompkins, founder of The North Face and Esprit, and his lifelong commitment to conservation and environmental protection. The biography tracks Tompkins from his early entrepreneurial pursuits in the outdoor equipment and apparel industry to his transition to impassioned advocacy for nature and the wild. Throughout that journey, regardless of where his focus was directed, Tompkins comes across as exceptionally intelligent, driven, competitive, creative, and perfectionistic. I couldn’t help but be reminded of Steve Jobs as portrayed in his biography by Walter Isaacson.

The book starts with Tompkins’ early years as a rebellious and adventuresome teenager ill-suited for the structure and discipline of a traditional and privileged private high school in the Northeastern US. He was a non-conformist who was unafraid to challenge the system, and he was ultimately expelled from school. One could surmise that succeeded in challenging the status quo, as he never graduated from high school and eschewed a college education he must have deemed not worth the time or investment.

An athlete and thrill-seeker who disliked rules, Tompkins easily gravitated towards outdoor activities that required skill and benefitted from imagination, creativity, and fearlessness. Skiing, rock climbing, mountain climbing, surfing, kayaking, and flying were among his favorite pursuits. His adventurous spirit also spurred him to travel and explore, both nationally and internationally. He landed in Northern California in his early twenties, where he met and began a lifelong friendship with a kindred spirit – Yvon Chouinard.

Chouinard and Tompkins fed off of each other in many ways as they both embarked on establishing high quality and sensibly designed outdoor gear and equipment for their new companies, Chouinard Equipment, Ltd. and the North Face, respectively. Chouinard’s focus was initially on technical climbing equipment while Tompkins mainly focused on clothing and accessories. They shared a love of the outdoors and adventure, they appreciated quality craftsmanship, and they saw a void in the marketplace as interest in the outdoors in the late 1960s and early 1970s was growing.

The first half of Franklin’s book focuses on Tompkins’ entrepreneurial spirit, business savvy, calculated risk taking, and splashes of luck. Tompkins and Chouinard were on the leading edge of an outdoor recreation revolution and it was all happening in the hippest coolest place to be in the world – San Francisco. They found themselves in the midst of music legends like the Grateful Dead and Janis Joplin, philosophers, scientists, and even like-minded entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs.

Perhaps Tompkins became bored by the success of the North Face when he sold the company in 1966 for $50,000 after having started it in 1964 using a $5,000 loan. He had met his first wife–herself an ambitious entrepreneur–during his North Face years, and had two daughters. Together they launched another world-renowned clothing and accessories brand–ESPRIT (initially founded in 1971 under the name Plain Jane), which became one of the most recognized global brands of the 1980s. Tompkins was involved in all facets of the business and established the highest bars for quality and aesthetics. He was a micro-manager of sorts and even volatile when things didn’t meet his expectations, especially aesthetically. He hired world-renowned architects and designers to design the retail stores. He was a student of these disciplines, meaning his input wasn’t based on personal preferences alone, but supported by a deep understanding of design and design principles.

Franklin’s description of Tompkins’ work ethic suggests it was all consuming, so much so that his family took a back seat. This is perhaps the saddest aspect of Tompkins’ life that hovers in the background of his story. When Tompkins did take a break from work it was to recharge his own batteries and focus on himself and his passion for outdoor adventure. Each year, he took three months off to chase down his bucket list–trekking in Siberia, surfing in Southern California, and of course climbing Fitz Roy in Patagonia. It was this trip which perhaps triggered his mid-life shift from realizing notoriety and riches through the manufacturing and selling of consumable goods to dedicating his life to the protection and conservation of wild natural areas at scale. The second half of the book is dedicated to this shift and Tompkins’ unyielding commitment to fight for Nature.

Tompkins reached some sort of tipping point in the late 1980s. He and his wife divorced, he sold his stake in Esprit for $150MM, and he embarked on a quest to conserve some of the most beautiful open spaces he had observed in South America. It was in this second phase of life that Tompkins met his soulmate, second wife, and in many ways positive counter measure, Kris. He met Kris through his good friend Yvonne Chouinard – Kris was Patagonia’s CEO and a force to be reckoned with in her own right. The perfect complement to Tompkins’ hard charging, take-no-prisoners demeanor, Kris was known for her calm and stable temperament, which came in handy when closing deals and brokering transactions in foreign environments. Kris was an equally passionate conservationist and outdoors person and brought original and innovative ideas to their quest to protect large tracts of open space. Without Kris, much of the Tompkins’ land acquisition pursuits would not have succeeded due to his confrontational, alpha male personality. They became an effective team, deeply committed to the goal of acquiring large contiguous tracts of open space in Chile and Argentina to set aside in perpetual conservation. They accomplished this by entering into agreements with the local and national governments to establish and recognize the lands as national parks to be accessed by all and to be protected forever. They had the benefit of having substantial financial resources and they were also adept at leveraging a number of their wealthy friends to back their conservation initiatives. But what is clear from the Tompkins’ story is that money alone won’t guarantee the conservation successes they achieved. It takes drive, persistence, perseverance, and smarts.

Tompkins’ was a once-in-a-generation kind of pioneer. Imagine if all of the world’s wealthy philanthropists shared that level of commitment to Nature.

Can we be hopeful that there is a new generation of pioneers making change at the intersection of business and the environment? What about the Jeff Bezoses and Mark Zuckerbergs of the world…and all of the young creators of products, “content,” and technologies that so quickly became part of our daily lives? I wonder about their philanthropy and causes and if they will ever have an awakening inspired by Nature. But perhaps I ought to look in a different direction. Perhaps the answer to my question can be found a lot closer to home. Isn’t it more likely found in the people behind the companies that are transforming the very way they are owned and governed in order to put purpose before profit? These are a new breed of pioneers, and they include not only the leaders of these businesses, but the employees. Luckily for me, I have this all around me. I work for a purpose driven organization focused on restoring the earth and inspiring ecological stewardship, and my teammates are inspirational in their commitment to that purpose. They are where I find hope and optimism that we can and will make a difference.