So ingrained were they in the cultures in which they existed there is actually a glossary of more than 120 peatland terms unique to just one three-county region of Scotland. How is it that so little was—and continues to be—understood about such landscapes?

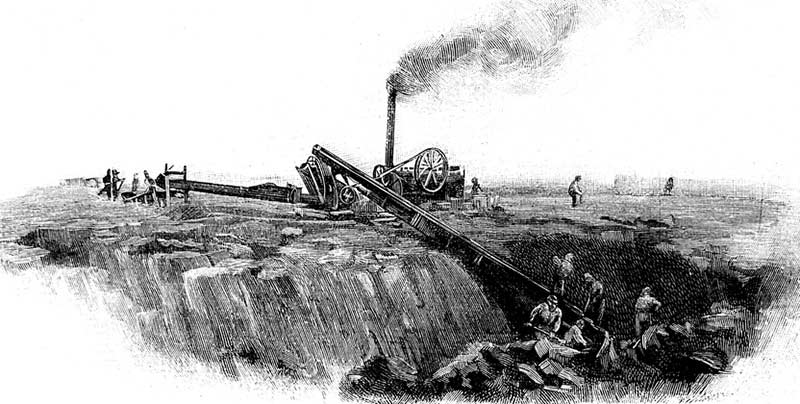

PEAT EXTRACTION IN THE 19TH CENTURY ©CLU | ISTOCKPHOTO

By the middle of the 20th century, society’s regard for peatlands was likely elevated by the discovery of peat’s usefulness as a soil amendment, but as we now know, the extraction of peat for any purpose comes with consequences. Today, as awareness of the need to protect biodiversity and adapt to a changing climate grows, people are, at long last, recognizing peatlands for the life-sustaining services they provide.

Peatlands contain 10% of global freshwater resources, offer unique habitat, minimize flood risk, sustain local economies, provide safe drinking water, and preserve thousands of years of archeological and ecological history. And when it comes to storing carbon, peatlands are one of the most valuable ecosystems on the planet. Though they cover only three percent of global land surface, they represent close to half of the world’s wetlands and they store 550 gigatons of carbon. If you, like me, are incapable of wrapping your brain around a gigaton, know that 550 gigatons is more carbon than is stored by all other vegetation types in the world combined–twice as much as is stored in all of Earth’s forests, which cover about 30% of the planet’s land surface.

Peat bog in Mantet, France

But here’s the rub: when a peatland is disturbed—by ditching, draining, fire, or a warming climate—it can very quickly go from being a carbon sink to a carbon source, releasing thousands of years’ worth of carbon into the atmosphere.

Peat extraction © Sergey Bogdanov | Dreamstime.com

There is good news, however. First, peatlands are still being discovered. As recently as 2016, researchers in the Congo Basin discovered a tropical peatland larger than the size of England. But these peatlands, like all remaining peatlands, must be protected. Second, while degraded peatlands can never fully become what they once were, they can be restored-as carbon sinks and as functioning ecosystems. In fact, at the 2010 Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, then Executive Director of the UN Environmental Programme, Achim Steiner said, “Restoration of peatlands is a low hanging fruit, and among the most cost-effective options for mitigating climate change.”

Are the 180 nations in which peatlands exist going after that low-hanging fruit? Are they incorporating peatland protection and restoration in their climate action plans? How does one go about restoring a peatland? How much do we really understand about this sensitive, but critically important ecosystem?

To address these questions and more, we turned to three experts.

Dr. Dale Vitt

First, we chat about the fundamentals of peatlands with Dr. Dale Vitt of Southern Illinois University. An expert bryologist and noted peatland ecologist, Dr. Vitt has devoted decades to studying–and inspiring others to study–one of the world’s most underappreciated, least understood ecosystems.

For a global perspective, we turn to someone who has not only studied peatlands all over the world but lobbied for their protection on the international stage. Peatland expert, paleoecologist, educator, and Secretary-General of the International Mire Conservation Group, Dr. Hans Joosten of the University of Greifswald describes the diversity and vulnerability of the world’s peatlands.

Next, we speak with a peatland restoration pioneer. Dr. Line Rochefort, founder of the Peatland Ecology Research Group at Université Laval, Québec, Canada, shares insight into the joys and challenges of restoring peatland ecosystems.

Our own senior ecologist and New Jersey native, Terry Doss, takes us on a photographic tour of peatlands in her home state with Peatlands of New Jersey: Inexhaustible Stores of Fertility.

We shine our Non-Profit Spotlight on the Yorkshire Peat Partnership, a UK-based organization that is actively working to restore, conserve, and research what they deem “The Cinderella Habitat” of ecosystems.

Senior landscape ecological planner/designer Jennifer Dowdell spends time Exploring the Depths as she reviews The Dark Stuff: Stories from the Peatlands by Scottish poet, Donald S. Murray.

A peatland in Iceland ©Jennifer Dowdell

For those who want to dig deeper into the subject of peatlands, we provide a list of organizations, publications, and other links and resources. Finally, we introduce our newest team member, highlight some award-winning projects, list our current job openings, and share the latest news at Biohabitats.

Before signing off, I leave you with this excerpt from the Gerard Manley Hopkins poem “Inversnaid,” which strikes me as a beautiful call for the conservation, restoration, and celebration of peatlands:

What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left,

O let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

Do you have thoughts to share about this issue? Is there a topic you’d like to see us explore in a future issue of Leaf Litter? Contact me. I’d love to hear from you.

Amy Nelson, Editor