You Can Do THAT with Fungi?

By Amy Nelson

Fungi’s contributions to life on Earth are not limited to their important roles in ecosystems, medicine, and cuisine. In fact, fungi hold enormous potential to enhance sustainability by serving as natural, renewable, biodegradable, non-toxic alternatives to many products we use daily. Here are just a few examples…

Pesticides

Chemical pesticides, which are often broad-spectrum agents, can not only cause ancillary damage to non-targeted species, but also long-term damage to the environment and human health. Entomopathogenic fungi, which attack specific insect species, hold promise as an alternative to chemical pesticides.

These fungi, which can be found among five of the eight fungal phyla, attack insects because they need them for survival and reproduction. A well-known (and downright creepy) example is seen in tropical rainforests, where fungi of the genus Ophiocordyceps will not only kill carpenter ants (Camponotus spp.), but control their behavior before doing so. A few days after being infected with the fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis (AKA “Zombie Ant Fungus”), the carpenter ant Camponotus leonardi will leave the safety of its nest, stumble about, and then, at a specific time of day, climb approximately 25 cm up a tree, where it will clamp its mandibles down on a leaf and die. Within 24 hours, fungal threads emerge from the ant’s carcass. Soon afterwards, a mushroom stalk grows out of the carcass. The mushroom then releases spores, which disperse on the forest floor and infect more ants.

After putting his knowledge of entomopathogenic fungi to work to address a carpenter ant infestation in his home, Paul Stamets received a patent for the use of pre-sporulation fungal mycelium as a biopesticide.

Fuel

Fungi’s ability to break down and convert a wide variety of different biomass into fuel makes it an appealing collaborator for biofuel researchers. Researchers at the University of Washington are working to develop an aviation biofuel using the fungi Aspergillus carbonarius ITEM 5010. Researchers at the University of Michigan have put Trichoderma reesei fungi and the bacteria E. Coli together to jointly convert plant matter into cellulosic fuel. Earlier this year, a study published in the journal Science showed that anaerobic fungi from the guts of sheep and goats outperformed the best genetically engineered enzymes produced by the biofuel industry.

Raw Materials

A wedding dress made of fungi? Really? Yes, really. In 2014, for her master’s thesis in design and fabrication at New York University, Erin Smith fabricated a wedding dress—a single-use object typically requiring energy-intensive production—using fungal mycelium. Now an artist focused on themes of sustainability, waste, and the future of fabrication, Erin has continued to create GrowableGowns and she has even done speculative design for Microsoft, looking at the future of biointegraton in wearables. Erin’s work has been exhibited at Microsoft’s Studio 99, Biofabricate, ISEA, and the Radical Mycology Convergence.

Fungi-based fashion is not limited to frocks. The San Francisco Startup MycoWorks combines mycelium and agricultural byproducts to make material resembling leather. Not only is this material 100% biodegradable and infinitely renewable while being cost-competitive, it can be grown to simulate various animal skins, and according to reviews, it actually feels and breathes like leather.

MycoWorks was started by an artist and cook named Phil Ross who became fascinated with mushrooms. As an art project, Phil decided to create architectural models out of mycelium. This led to the creation of mycelium-based interlocking bricks for building. These bricks are not only a sustainable, non-toxic alternative to synthetic building materials; they are strong, lightweight, compostable, and fire-resistant. MycoWorks is not the only company that has recognized the potential to transform the building industry.

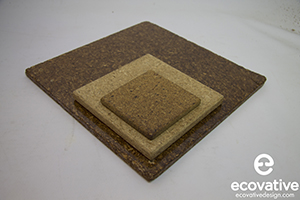

Even many ubiquitous synthetic plastics can be replaced by fungi. Just as some of the world’s greatest minds are at work trying to remove the plastic debris choking our oceans, a set of Dutch researchers at the University of Utrecht are at the forefront of developing organic materials to replace plastic in everyday objects. The basic process is to allow fungi to grow a network of filaments into a desired shape or substrate. For example, with the correct species growing into and through wood pulp, the mycelia will penetrate the pulp, digest much of it, and bind together the leftovers, forming a strong composite of fungus and wood. Once the fungus has been grown into the desired mold, its progress is arrested with heat. The final product is much like cork. The material is light, strong, and water resistant. It is being used in furniture and for novelty items today, but researchers, designers, and entrepreneurs are equally confident that the field is at the cusp of major breakthroughs that will allow the mass production of common materials within a decade.

Ecovative, a company founded in 2006 by two Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute graduates who had invented an insulation material using agricultural waste and mycelium, has made major headway in transforming the packaging industry. Within two years of starting their company, Eben Bayer and Gavin McIntyre found themselves manufacturing mushroom-based packaging for companies like Dell and Crate & Barrel.

As shipping becomes ever faster and easier and the packaging market grows, the use of fungi as an innovative approach to packaging has taken off quickly, especially for industries that require firm molds to secure their shipped product. Fungal packaging functions like Styrofoam, but unlike Styrofoam, it can be used for compost without any treatment, greatly reducing the immediate and long term cost of disposal. Ecovative has since expanded into building materials, and earlier this year, they launched a line of interiors, which includes fungi-based wall tiles and furniture. Ecovative’s Grow It Yourself (GIY) Material, which they began selling in 2014, has likely inspired countless creations. Take Brooklyn-based designer Danielle Trofe’s stylish MushLoom lighting collection, for example. And remember Erin Smith’s wedding dress? It was made from spores from Ecovative.

“The process of making this dress really allowed me to engage in some blue sky thinking about the direction I wanted to see manufacturing go,” said Erin. Though her dress was not ready in time for her wedding, the process of designing and fabricating it has changed her life. “Once you’re able to pin down what you want, for instance – a material with the lowest possible embodied energy and water use that can easily and rapidly biodegrade – then it’s a lot easier to start applying those desires to other parts of your life and working to make a positive change.”

These fungi, which can be found among five of the eight fungal phyla, attack insects because they need them for survival and reproduction. A well-known (and downright creepy) example is seen in tropical rainforests, where fungi of the genus Ophiocordyceps will not only kill carpenter ants (Camponotus spp.), but control their behavior before doing so. A few days after being infected with the fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis (AKA “Zombie Ant Fungus”), the carpenter ant Camponotus leonardi will leave the safety of its nest, stumble about, and then, at a specific time of day, climb approximately 25 cm up a tree, where it will clamp its mandibles down on a leaf and die. Within 24 hours, fungal threads emerge from the ant’s carcass. Soon afterwards, a mushroom stalk grows out of the carcass. The mushroom then releases spores, which disperse on the forest floor and infect more ants.

After putting his knowledge of entomopathogenic fungi to work to address a carpenter ant infestation in his home, Paul Stamets received a patent for the use of pre-sporulation fungal mycelium as a biopesticide.

Fuel

Fungi’s ability to break down and convert a wide variety of different biomass into fuel makes it an appealing collaborator for biofuel researchers. Researchers at the University of Washington are working to develop an aviation biofuel using the fungi Aspergillus carbonarius ITEM 5010. Researchers at the University of Michigan have put Trichoderma reesei fungi and the bacteria E. Coli together to jointly convert plant matter into cellulosic fuel. Earlier this year, a study published in the journal Science showed that anaerobic fungi from the guts of sheep and goats outperformed the best genetically engineered enzymes produced by the biofuel industry.

Raw Materials

Even many ubiquitous synthetic plastics can be replaced by fungi. Just as some of the world’s greatest minds are at work trying to remove the plastic debris choking our oceans, a set of Dutch researchers at the University of Utrecht are at the forefront of developing organic materials to replace plastic in everyday objects. The basic process is to allow fungi to grow a network of filaments into a desired shape or substrate. For example, with the correct species growing into and through wood pulp, the mycelia will penetrate the pulp, digest much of it, and bind together the leftovers, forming a strong composite of fungus and wood. Once the fungus has been grown into the desired mold, its progress is arrested with heat. The final product is much like cork. The material is light, strong, and water resistant. It is being used in furniture and for novelty items today, but researchers, designers, and entrepreneurs are equally confident that the field is at the cusp of major breakthroughs that will allow the mass production of common materials within a decade.

“The process of making this dress really allowed me to engage in some blue sky thinking about the direction I wanted to see manufacturing go,” said Erin. Though her dress was not ready in time for her wedding, the process of designing and fabricating it has changed her life. “Once you’re able to pin down what you want, for instance – a material with the lowest possible embodied energy and water use that can easily and rapidly biodegrade – then it’s a lot easier to start applying those desires to other parts of your life and working to make a positive change.”