Beaver are considered a keystone species because they create habitat for entire ecological communities, including many species that evolved in response to the beaver’s influence on their habitat. Before humans arrived on the scene about 15,000 years ago, it is estimated that there were 60 to 400 million beaver, and at least 25 million beaver dams, distributed across most of North America.

“Man was lord of the dry land and the beaver reigned over the rest,” reported David Thompson, an early European colonist and explorer, circa 1748. North America First Nations communities, developed in close association with the beaver, lived off the concentration of wildlife and plants that occurred near the beaver ponds. There are many First Nations myths involving men and women who turn into beaver, live with beaver for years, and return to their original form to share lessons about hard work, long-term planning, cooperation, and other attributes learned from their cohabitation with the beaver. In recounting how the start of the European colonization of North America was fueled by a demand for beaver skin with its useful and attractive fur, Backhouse paints all too clear a picture of how calling this product a “pelt” minimized the tragedy and waste of the resource. I was surprised to learn that many First Nations people helped facilitate this harvest, communicating the demand to other distant peoples, over-harvesting local beaver populations, and delivering European beaver trappers to remote locations.

After years of overharvesting beaver populations and largely eliminating beaver from entire regions of the early nation, select members of society began to take measures to restore beaver to the landscape. Perhaps not surprisingly, one of the first to institute protections was the Hudson Bay Company, the iconic fur trading company. Beaver trapping was an important economic engine, and the Hudson Bay Company was watching harvests and fur quality decline as the most highly prized beavers from the north and east were being replaced by smaller beaver harvested from the south and west, where the fur was lighter in color, less lustrous, and in less demand. Stories of conservationists who lived in homes connected to beaver lodges, with beaver that curled up in front of their fireplaces in the winter, sound remarkably modern and fantastic.

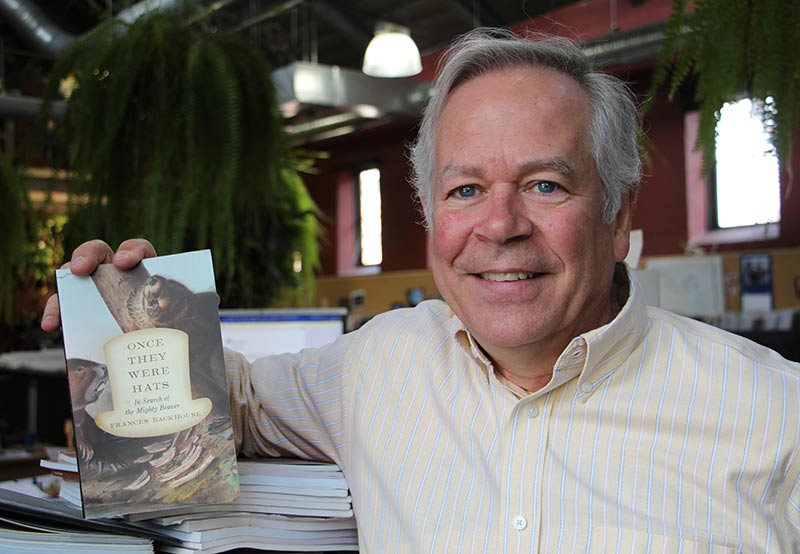

From this interesting description of the beaver-human story coexistence, to near genocide, to our recent strategy of benign neglect, the book shifts to a description of the qualities of beaver ‘under fur’ as a felting material superior to wool, cashmere, and other hat making materials. A quick search on the internet shows that beaver hats made from 100% beaver fur felt sell for about $1000, while the same product made from other materials sell for much less. Backhouse also highlights a surprisingly still burgeoning fur industry in North America that attracts buyers from China and Russia for mink, bear, timber wolf beaver, and muskrat. She even describes her lesson in beaver skinning to complete the immersion in society’s paradoxical relationship with the non-humans we share the planet with. While the image of early conservationists with beaver curled up in their living rooms may make us feel better about some of our fellow humans, a chapter on how scientists and restoration practitioners are advocating for the importance of beaver in our management of stream and fishery resources truly provides hope that beaver can once again deliver economic benefits to society. Through their natural behaviors and proclivities, beaver can restore our stream valleys, improve our aquatic and wetland habitat, and maybe even earn a valued place in our landscape–as long as they deliver value.

Backhouse points out that although landscape development, game laws, and old ideas about human-beaver conflict will never let the beaver return to pre-colonial population levels and distribution, they can and will return to many areas where they haven’t been for a couple hundred years. In my own recent experience at Biohabitats, I have seen beaver move into several of our stream restoration projects. I have also been pleased to see that in these cases, the local community response has generally been one of appreciation and sincere fondness of our wild, bucktoothed brethren.

…the local community response has generally been one of appreciation and sincere fondness of our wild, bucktoothed brethren.

I enjoyed this entire book and heartily recommend it. While not all of the content will be pleasant to read, it is a good representation of the recent past. European colonization of North America has been a problem for so many organisms (e.g., buffalo) and peoples, and its residue is responsible for much of the environmental degradation that exists today. Perhaps the book’s insight into our treatment of the beaver will help us to be better members of our natural community.

This is an easy-to-read, well-documented anthropomorphic history of the beaver in North America. Initially, I thought to call it a natural history of the beaver, but in reality, it’s less about beaver ecology than it is about the relationship between the beaver and society. That isn’t to say that this book doesn’t contain a sufficient coverage of the natural history of the beaver; it does.This book presents an overview of the evolutionary diversity of beavers, including descriptions of extinct beavers that ranged in size from that of a muskrat to that of a smallish hippo. Not all beavers build dams or use wood as does our most familiar beaver, Castor canadensis. While the beaver family has resided in North America for more than 37 million years, our familiar beaver has only manipulated and controlled the streams, wetlands, and floodplains of North America for about one million years.

This is an easy-to-read, well-documented anthropomorphic history of the beaver in North America. Initially, I thought to call it a natural history of the beaver, but in reality, it’s less about beaver ecology than it is about the relationship between the beaver and society. That isn’t to say that this book doesn’t contain a sufficient coverage of the natural history of the beaver; it does.This book presents an overview of the evolutionary diversity of beavers, including descriptions of extinct beavers that ranged in size from that of a muskrat to that of a smallish hippo. Not all beavers build dams or use wood as does our most familiar beaver, Castor canadensis. While the beaver family has resided in North America for more than 37 million years, our familiar beaver has only manipulated and controlled the streams, wetlands, and floodplains of North America for about one million years.