Expert Q&A: Cormac Cullinan

By Amy Nelson

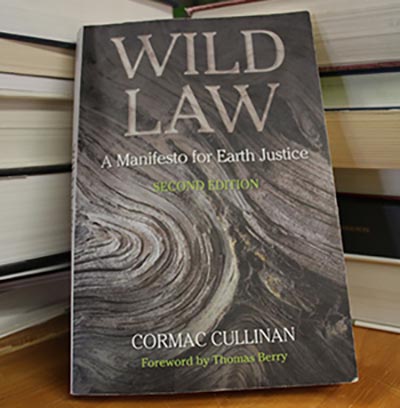

In his book Wild Law, now in its second printing, Cormac builds a compelling case for a pioneering legal philosophy that restores an ecological perspective to systems of law and governance. He has spoken about this philosophy to audiences around the globe, including the General Assembly of the United Nations. A founding member of the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature (featured in Leaf Litter’s Nonprofit Spotlight), Cormac led the drafting of the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth at the People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth in 2010. In 2012 he won the Nick Steele award for the South African environmentalist of the year.

As the director of an environmental law firm, you must have to work within the existing system of environmental law, while also trying to fundamentally change it.

I started out my environmental law career believing that we could solve our environmental problems by drafting and implementing better laws. I now believe that while we can win some important battles within the current governance systems, we cannot achieve ecological sustainability because these systems have been designed to facilitate the exploitation of Earth. In some ways, I would have preferred to have reached another conclusion, because this is an awfully big task to take on! But the fact of it is, we are born into this Earth community. As with any community, you have to live by the rules or you will eventually be excluded. Right now, many human beings seem to be working pretty hard to get excluded from the community of life on Earth.

You studied law in apartheid South Africa. How did that influence your ability to examine legal systems objectively, and what did it teach you about the concept of “restorative justice?”

One of the advantages of studying law in apartheid South Africa is that I became very conscious that a legal system is not neutral; it is based up on a specific world view. In South Africa, the dominant premise was that people are not equal, and that some races are superior to others. If you translate that into law, you can have a perfectly logical legal system which is also very unjust. My experience studying law in apartheid South Africa made me very conscious that legal systems are shaped by influential individuals, organizations, and lobby groups. This later helped me see how our legal systems are also based upon a specific world view: one in which only people and juristic persons, like companies, are legal subjects capable of holding rights. [In this world view] nature is a collection of resources to be used by human beings. We have shaped the rules of the game in a way which places the interests of property holders above the interests of the Earth community and of life itself. Property owners are entitled to do all kinds of things which are detrimental to the common good. Most of the activities that drive climate change, for example, are perfectly legal.

One of the advantages of studying law in apartheid South Africa is that I became very conscious that a legal system is not neutral; it is based up on a specific world view. In South Africa, the dominant premise was that people are not equal, and that some races are superior to others. If you translate that into law, you can have a perfectly logical legal system which is also very unjust. My experience studying law in apartheid South Africa made me very conscious that legal systems are shaped by influential individuals, organizations, and lobby groups. This later helped me see how our legal systems are also based upon a specific world view: one in which only people and juristic persons, like companies, are legal subjects capable of holding rights. [In this world view] nature is a collection of resources to be used by human beings. We have shaped the rules of the game in a way which places the interests of property holders above the interests of the Earth community and of life itself. Property owners are entitled to do all kinds of things which are detrimental to the common good. Most of the activities that drive climate change, for example, are perfectly legal.

Many indigenous legal systems have the concept of “restorative justice.” They understand the world as being composed of relationships between members of the community. When there is a problem, or somebody does something which the community regards as wrong, this is understood as something which has damaged a relationship, and the most important thing to is restore the quality of that relationship. The emphasis is far less on punishment and much more on healing the relationship so that the health and integrity of the community is restored.

Restorative justice was demonstrated in the transition from apartheid to democratic South Africa with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission established under the leadership of Archbishop Desmond Tutu. There was a recognition that apartheid had divided, hurt, and damaged the South African community deeply. One option [for seeking justice] was to find all of the people who had committed crimes under the apartheid regime and prosecute them. Although that might fit with normal concepts of criminal justice, it was agreed that the most important priority at that time in South African history was to heal the damage to human relations caused by apartheid and restore the health of the South African community. So it was announced that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission would grant amnesty to people who appeared before before it, disclosed the crimes that they had committed fully and truthfully (so that relatives of victims could find out what happened to their loved ones), and convinced the Commission that their crimes were politically motivated. People who had done terrible things—including torture and murder—were actually let off if they came clean. It was a very tough process because victims’ families had to listen to details of the atrocities that had been perpetrated and then know that if the perpetrator convinced the Commission that they had told the truth and had acted under political motivation, they’d be set free. It was by no means an easy process, but it’s an example of prioritizing the common good so that society can be healed.

This process [has yielded] some incredible stories of reconciliation which one would never believe possible. For example, a young American exchange student named Amy Biehl, who was working in South Africa [to help register voters for the country’s first free elections in 1994] was murdered for no other reason other than she was white. Amy Biehl’s parents later set up the Amy Biehl Foundation, a charitable organization [that now offers youth empowerment programs] in South Africa. The perpetrators were later released under this amnesty provision, and some of them actually ended up working for the Amy Biehl Foundation.

Restorative justice is an incredibly powerful concept, and it is particularly important in an environmental context. If someone pollutes a river and you send that person to prison, it may deter others from polluting, but it doesn’t’ help the river. The most important thing is to restore the quality of the river and a relationship of respect between humans and rivers.

Father Thomas Berry (priest, cultural historian, “geologian,” and author) seems to have played a major role in your involvement in and passion for the rights of nature movement. For the benefit of our readers, can you tell us a bit about Thomas Berry and his impact on you and on the movement?

Father Thomas Berry played a very important role in my intellectual development in relation to these issues. I had realized that there was something fundamentally wrong with the underlying philosophy of law and the world view that informed it, but was unsure about how to begin the process of rectifying it. I was introduced to Thomas Berry’s work through the Gaia Foundation in London. When I was eventually able to meet him, it was as if he gave me the end of the string, and then I could begin to unravel the whole problem.

When I first heard him say, “The world is not a collection of objects; it is a communion of subjects, and everything has rights” I was shocked. I thought, “Do you realize the implications of what you’re saying? That can’t be right. It’s too difficult to implement.” As I read and learned more, however, I realized I was making an error in saying something was wrong simply because it was difficult to bring about.

In a certain sense, Berry was using “rights” in an analogous way. What he was saying is that we are all part of a whole. We are all—whether we are a tree, rock, river, or person—products of the same evolutionary story of our planet, and each of us has a contribution to make to the integrity, functioning, and health of the whole.

Thomas Berry can be considered to be a father or the rights of nature movement. He pointed out that the current mode of civilization is transient. He referred to the times that we live in as the “petroleum interval.” Although to those of us born in the last few centuries, it may seem seem that our societies have always been this way, if one looks at the entire span of human history, this period is an aberration. During this period human lives have changed enormously, largely because we have been able to draw on the energy in fossil fuels in order to increase our power, and because we have changed our philosophy from respecting Mother Earth to exploiting Mother Earth. We now see that this project of exploiting and attempting to control Earth is doomed to failure. Although it will take quite some time for this to play out, we are passing into a new era, where people will either become extinct or move into what Berry calls the “Ecozoic Era”-an era in which we recognize that our role is to live in a way that enables us to fit in with the preexisting laws of the universe, and to work with nature instead of attempting to control it.

Humans did not start off neglecting the rights of nature. In your opinion, when did things take a turn for the worse, and what caused this change in world view that is so destructive to the planet?

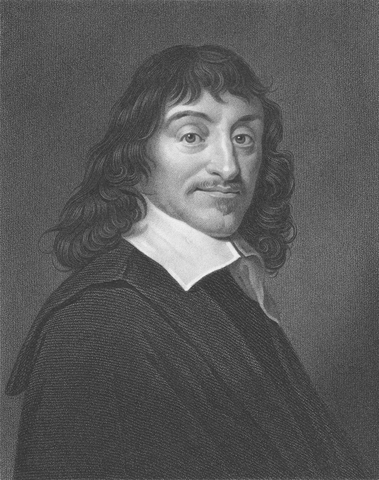

It is difficult to identify a particular point at which that change occurred. It was more of a process with milestones along the way. Some people point to the beginning of agriculture, but I see the Age of Enlightenment in 16th and 17th century Europe as one of the major milestone. It was a time of thinkers like René Descartes and Francis Bacon, and the emergence of the scientific method and the belief that humans were fundamentally different from everything else on the planet.

At that time, there was a shift away from seeing Earth as a mother who fed, nourished, and educated her children, to using the metaphor of a machine to explain the universe. People began to understand Earth and our solar system as something that functioned like a complex clock, and the object of science was to learn how to dissect Nature in order to understand how it worked and how to operate it to the benefit of humans.

The role of the human began to be seen as master of the universe, and the role of science was to achieve mastery over nature. Everything [non-human] was considered soulless and viewed in mechanical terms. There are references from that time, for example, in which the screams of animals being experimented upon were said to be “like the squeaking of a rusty hinge.”

Another major milestone was the Industrial Revolution, when we discovered that we could use coal, oil, and gas as sources of power. That drastically increased our capacity to change the world, and it was like a steroid boost to our egos. Gaining access to that additional energy separated us further from the natural world, and fed our fantasy of superiority.

Do you think a change in world view will happen in your lifetime?

It’s already happening. Since Ecuador’s 2008 adoption of a new constitution which recognized the rights of nature, and the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth in 2010 there has been a huge upsurge of interest in these ideas. I have no doubt that the world views of more and more people are changing. But it takes much longer to actually change the structure of society. I don’t imagine that process will be completed within my lifetime, but I find it very heartening to know that is has started in my lifetime.

Doe the creation of a new legal system require a change in world view? Does one have to come before the other? Is the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth pushing both?

It is both. Sometimes changes in the law will shift people’s world view, and other times one has to first change people’s world view before one can change the law. For example, in South Africa, the day the new constitution which prevents racial discrimination came into force, there were still the same number of racists in South Africa as the day before., However because the law no longer favored racists, it is gradually helping to eradicate racism. But that constitution would never have been put into place without a movement of people who struggled for many years to bring about a constitution that reflected their world view.

Can you define and describe the difference between “the Great Jurisprudence,” “Earth jurisprudence,” and “wild law,” and explain why these distinctions matter in the pursuit of legal systems that recognize the rights of nature?

The term “jurisprudence” means the philosophy that informs law. Thomas Berry pointed out the need for a new jurisprudence because existing philosophies of law view Earth as property that can be bought and sold in the same way as buying and selling a slave.. It’s easy to see that when you have a slave owner with all the legal rights, and a slave who is property and therefore incapable of holding legal rights, the slave owner will always exploit the slave. That is exactly the same exploitative relationship the law has created between humans and companies on the one hand, as the holders of rights, and all of nature on the other, as property incapable of holding rights.

In order to distinguish the kind of jurisprudence Thomas Berry called for from conventional jurisprudence, I use the term “Earth jurisprudence.” This term is intended to indicate a philosophy of law that is based on recognizing the importance of the Earth community as a whole, and not just the human community. Laws are typically enacted to promote harmony and stability within a human community. Earth jurisprudence is intended to do that within the larger community of all life on Earth. So under a philosophy of Earth jurisprudence, human laws would be designed to ensure that humans act as responsible members of the Earth community.

But we are born into a universe with pre-existing systems of order. Forces of gravity, for example, ensure that Earth moves around the sun. There is a logic which informs how the universe works, and which we refer to when we use terms such as the laws of nature, physics, or chemistry. They are something akin to laws which predate humans. To describe them, I use the term “Great Jurisprudence.” It is the wisdom inherent in the principles of nature. Different cultures could have different Earth jurisprudences, but all of them should align with the Great Jurisprudence, and all should be informed by the recognition of the importance of working in harmony with nature. This is something you find in all indigenous cultures. The first duty is to teach young people about how nature works in that place and the importance of respecting the laws of nature.

The Great Jurisprudence informs the design of Earth jurisprudences. Then, the actual laws that reflect that Earth jurisprudence are what I call “wild laws.” It’s a term that seems an oxymoron to conventional legal minds because “law,” as we know it, is designed to constrain, control, and regulate, and “wildness” means the opposite. But there is an extraordinary, creative force at work in the universe. It’s the force that created this planet from a gaseous mass and star dust, and then diversified it into redwoods, blue whales, insects, and humans. It is a force that has driven an explosion of diversity, and it cannot be controlled in a mechanical way. It is quintessentially wild. Wild laws enhance that creative quality of the universe. The should be designed to enable us to achieve our full potential while leaving space for all other beings to fulfill their potential. Wild laws stands in opposition to laws that impose homogeneity and the “monocultures of the mind” that Dr Vandana Shiva warns against. A wild law is informed by an Earth jurisprudence, which is informed by the Great Jurisprudence.

In your recent article “A Tribunal for Earth: why it matters,” you pose this compelling question: “Must contemporary civilisation burn to provide the ashes from which an entirely new civilisation will be borne? Or is it possible for the shoots of a fundamentally new governance system to grow amidst the decay of contemporary systems?” In the ashes of our decaying legal systems, are there any embers worth keeping alive and building upon?

There are many good elements in contemporary legal system. The concept of human rights has changed legal systems for the better. For example, the current South African constitution states that you may not discriminate against people on the basis of race, gender, or sexual preference. That is a recognition of human rights, but also of the importance of diversity. Diversity is one of the principles on which the universe operates. I see it as part of the Great Jurisprudence. To get people to entrench in law the idea that diversity is something to be celebrated and not eliminated is important.

The main thing that needs to change about our legal system is the purpose underlying it. The underlying purpose of most legal systems is to facilitate and legitimize the domination and exploitation of everything that isn’t human (and in some cases, certain human beings as well). If that purpose became “to enable us to live harmoniously with our fellow Earthlings in a way that is mutually beneficial,” we could completely transform our legal systems for the better.

What are some of the common themes that emerge when you examine systems of law and governance that exist among indigenous cultures and fall within the framework of the Great Jurisprudence.

For many indigenous cultures, the concept of rights of nature is actually foreign, because they don’t even have the world “right” in their languages. The integral world view—the view that humans are part of a larger community, and our health and well-being is derived from the health and well-being of the entire community—is foundational for every indigenous culture I’ve ever come across. Indigenous communities spend an enormous amount of time inculcating all members of the community—by way of stories, rituals, and practices—with respect for other beings and for the principles of reciprocity. Rules of indigenous cultures differ from place to place, but they are very much informed by the wisdom of a particular place. If it’s a dry area, there will be complex laws about the allocation of water and water rights which are unlikely to have evolved in a rainforest. In indigenous cultures, humans have adapted themselves to be good neighbors in the community in that particular place, and they have adapted their customs and laws accordingly. That’s the kind of approach that the rights of nature movement is advocating. You don’t start with a blank slate and try to impose your views on a place; you must pay attention to the community you are a part of, and work out how to be a good, responsible member of that community

In response to the failure of the COP15 (to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) to make significant progress in reducing global emissions in 2009, Bolivian President Evo Morales held the World Peoples’ Conference on Climate Change in 2010, a gathering of over 30,000 people from more than 100 nations. During that event, a Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth was crafted. What is happening with that declaration now? Is it being discussed at other international conventions?

President Morales originally called for a Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth to contextualize the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. He pointed out that when we only recognize human rights, we create an imbalance. Human rights must be seen within the context of a world where other beings also have rights. As I understood it, he originally envisaged that the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth would be adopted by the United Nations in the same way as it adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights after the Second World War. But what ended up happening is that he convened a People’s Conference, which anyone in the world could attend, and about 35,000 people did. Different working groups came up with recommendations on different areas, and at the end of the conference, these were presented to the many governments that also attended. So instead of the governments telling the people after the conference what they had decided (as is the case with UN climate talks), it was the other way around. The people told the governments “This is how we think we should deal with these problems”. At the end of the World Peoples’s Conference, the Conference as whole adopted The Universal Declaration of the Rights of Nature as a “people’s document.” People said, “This is our document. We don’t need government to make this declaration. We call on governments of the UN to sign onto it, but it has its status as a people’s document whether they do that or not.

The UN has actually set up a web site dealing with living in harmony with nature, and at least once a year, they convene expert discussionson this topic. Countries like Ecuador, Bolivia, and Venezuela support the adoption by the UN of the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth but they are in a minority. It’s unlikely that the Declaration will be adopted by the UN in the near future. But organizations like the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, and La Via Campesia (an organization representing millions of small scale, peasant farmers), and other organizations that attended the People’s Conference, are supporters of the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth, and they are advocating that it be implemented regardless of whether or not the UN adopts it.

It is very clear that the principal challenges of the 21st century, like climate change, cannot be adequately solved within the system of governance that created them. The power of the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth is as a people’s document which more and more people around the world are finding meaningful and are supporting. The Declaration is a way of uniting a global movement. If a community in India is fighting a proposed mine on a sacred mountain, and another community on the other side of the world is also trying to protect itself against mining, when they present their cases before the Tribunal it becomes clear that both are examples of the violation of the same universal rights. It also shows how very local impacts are also universal.

One of the ways we are doing that is through the establishment of the International Rights of Nature Tribunal, a body created by people, rather than government. The Tribunal is intended to show how different the results would be if we decided the big issues of the day with reference to the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth instead of the conventional international law based on property and the sovereign rights of states.

The International Rights of Nature Tribunal has convened twice, with a third session scheduled for this December in Paris. You have served as a judge on the Tribunal, and you delivered a preliminary finding in the case involving the impact of industrial development and coal port expansion on the Great Barrier Reef. (The case then went to a full hearing at the Second Tribunal.) What was it like to hear a case presented on behalf of the Great Barrier Reef, which cannot speak for itself?

It is very moving to hear a case presented from the perspective of the Great Barrier Reef. The way environmental matters [like this] are normally dealt with in our court is that some fisherman will come in and say, “I used to earn $20,000 a year, and now I only earn $10,000 a year because there are fewer fish because of pollution.” The discussion is almost always associated with the impact on human beings, particularly concerning money. But when you see cases presented in terms of what it must feel like to be a reef or a creature in the reef suffering enormous impacts, and seeing your world, culture, and relatives destroyed, it causes people to empathize—perhaps for the first time–with the other members of the community of life. That can be extraordinarily powerful. Einstein talked about the importance of “widening our circle of compassion.” If you sit in one of these sessions and listen to these cases, it can be quite harrowing. But it also opens one’s heart and enlarges one’s circle of compassion.

Do the parties accused of violating the rights of nature ever attempt to defend themselves at the Tribunals?

We have invited them, but so far none of them has appeared. Because the Tribunal is not something established by a government, we have no power to compel people to come. Unfortunately, the Tribunal suffers from the limitation that the accused usually choose not to attend. Nevertheless it work well enough to demonstrate how to apply the rights and duties in the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth.

At this time, is the Tribunal the most powerful potential replacement for what you refer to as our “obsolete” international mechanisms in your recent article “A Tribunal for Earth: why it matters”?

I certainly think it’s one of them. People are beginning to realize that climate change is not just a scientific issue; it involves human rights violations on a massive scale. I think those discussions will broaden beyond human rights to recognize that it’s not just the rights of humans that are affected. I believe, from what I have seen of international meetings, that it is impossible to get the kind of agreements that we need to deal effectively with challenges like climate change through those forums. There are just too many countries there, and many of them are acting out of their own self-interest or they are very heavily influenced by corporate lobbyists.

The international system was supposed to deal with these issues, but if it doesn’t, and year after year goes by without any realistic way forward, it’s like damming a river. The pressure mounts until eventually the river cuts a new path that goes around the blockages in the system. That is what we see happening with initiatives like the Tribunal. People are saying, “You know what? If our government is not going to work out a route to a viable future for us, we are going to do it ourselves.”

In Wild Law, you wrote: “Even if a legal system were to recognise that other species are beings, we must still overcome the difficulties of how any ‘rights’ that they may have will be protected and asserted.” How has the inclusion of rights of nature in Ecuador’s constitution translated to action?

Although the Ecuadorian constitution is very strong on the rights of nature, the current government has retreated to quite a large extent from some of those provisions. Before this retreat, there were some examples of effective action on the ground. One was of the case of the Vilcabamba River. A road next to a river was being widened by the provincial government. They cut into the mountain, and tipped the rock and earth into the river, which caused flooding and erosion downstream. A case was brought to court in the name of the river. The Vilcabamba River actually sued the provincial government, and it won. The court found that the river had the right to flow unimpeded, because that was its natural, ecological function, and that it was possible to widen the road without interfering with the river’s rights. The human interest in widening the road could not trump the fundamental rights of the river to flow and be a river. It was an extraordinary decision. If a case like that were taken under conventional legal systems, it’d probably be a very technical argument about whether or not the road builders and government complied with procedural requirements of the environmental impact assessment process. It would be a discussion about procedures and processes, which has nothing to do with resolving the fundamental issue of how to balance what humans want with what is good for the the planet as a whole.

Despite the Ecuadorian government’s backsliding, do you think we will see an increase in precedent-setting cases like the Vilcabamba River?

I do. I think it will be a long, slow process, but we will see little pockets breaking out all over the world. Dozens of communities in the U.S., for example, have passed bylaws recognizing rights of nature. [The rights of nature movement] is starting to build alternatives to the current system, and that is important. Many people are disaffected with how our legal, political, and economic systems are working, but they don’t know what else to do, so they stay with them. But as soon as you give them an alternative, they are going to start moving [towards that alternative].

What is the role for academia in this movement? Are students of law starting to become interested in the rights of nature?

Many of the students I have met who have discovered the concept of rights of nature seem to have been unconsciously looking for it. A lot of young people are realizing that we need to work with nature. Most academics didn’t seem to take rights of nature seriously until there was some text on the subject. Now that we have the constitution in Ecuador, laws in Bolivia, community ordinances in the USA and the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth, and the International Rights of Nature Tribunal is beginning to produce judgements, there will be more and more text for people to discuss. It is a very exciting opportunity for academics to rethink everything from a new perspective–to take a piece of law or a judgement, and think, “How differently would this have been written if it were coming from the perspective of promoting humans living as good Earth citizens in harmony with nature?” It is challenging, but enormously rewarding.

Do you have any words of wisdom or advice for practitioners of conservation and ecological restoration (many of whom are involved in mitigation projects resulting from current environmental law)?

If you are involved in ecological restoration, you are involved in restorative justice. As a species, we have to do what we can to heal the earth and ensure that new harm doesn’t occur. The thinking that informs the rights of nature movement is emerging all over. In agriculture, you have permaculture. In architecture, you have green architecture. This thinking asks, “How can we begin to work with the grain of nature in a way that promotes human well-being and the well-being of the community as a whole.” All of us in our different fields are engaged in bringing about a world in which the role of a human is to be a good Earth citizen, instead of the slave master in charge of the community of life. I am very hopeful that people working in these different areas can begin to recognize their common interests and recognize that if the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth were enforced everywhere, a large amount of society’s resources would be devoted to restoring ecological systems to health.