While serving at the Museum, he has carried on an active research program dealing mostly with the comparative biology of adult and immature bees and their evolutionary relationship on a worldwide basis. In conducting this research, he has traveled to more than 20 countries and published over 160 papers. With others, he has developed and administered an annual international workshop on bees, the Bee Course, for the past 18 years, held at the Museum’s Southwestern Research Station in Arizona. Dr. Rozen is currently working on research projects pertaining to the structure and adaptive function of bee cocoons, particularly with respect to those of leaf-cutter bees (Megachilidae). We were delighted to visit him in his office at American Museum of Natural History and see what is believed to be the most complete collection of bee eggs, larvae, and pupae worldwide.

How did you become interested in bees?

I have always been interested in natural history. As a kid, I had a butterfly and moth collection. When I had a chance to go to Arizona as a 14-year-old, I collected lizards, snakes, and even a porcupine. In high school, I dated a girl who happened to live next door to the chairman of the entomology department of the American Museum of Natural History. After graduation, I went to college at the University of Pennsylvania but [my girlfriend] had to wait because this was just after the Second World War, and the universities were crowded with ex-GIs. So she went to work in the Museum for a year.

I have always been interested in natural history. As a kid, I had a butterfly and moth collection. When I had a chance to go to Arizona as a 14-year-old, I collected lizards, snakes, and even a porcupine. In high school, I dated a girl who happened to live next door to the chairman of the entomology department of the American Museum of Natural History. After graduation, I went to college at the University of Pennsylvania but [my girlfriend] had to wait because this was just after the Second World War, and the universities were crowded with ex-GIs. So she went to work in the Museum for a year.

Dr. Rozen in his office today (foreground) and in the field decades ago (background photo)

I’d come home from college on weekends and take her out on dates, and occasionally show up at the Museum, so I got to know a few of the curators. She had to leave her job at the Museum early to be a camp counselor before heading to college, and she asked if I would like to have the last two months of her appointment. I did, and that is when I became interested in entomology. I returned to the University of Pennsylvania for my second year, but since they didn’t have much entomology at that time, I decided to go to the University of Kansas at the start of my third year, where there was a new entomology chairman who had been a curator at the American Museum of Natural History. He was doing research on the thing that interested him most: bees. His name was Dr. Charles D. Michener, and he was the leading world authority of bees for many years. Under his influence I became very interested in bees.

I understand that there are over 20,000 species of bees in the world. A quote by your colleague John Ascher really brings that home: “There are actually more species of bees than of birds and mammals put together.” Can you tell us a bit about bee diversity?

I understand that there are over 20,000 species of bees in the world. A quote by your colleague John Ascher really brings that home: “There are actually more species of bees than of birds and mammals put together.” Can you tell us a bit about bee diversity?

That is true. I keep telling people that there are as many different kinds of bees in the world as there are kinds of bony fishes in the world. That’s all the fish that live in coral reefs, in fresh water, and in salt water, and in the depths of the ocean.

Interestingly enough, the sex of a bee is as important (in terms of its effectiveness as a pollinator) as the kind of the bee. Male bees are not as good at pollinating as females because most female bees visit flowers far more often to collect food not only for themselves but for their offspring. Males just go only to feed themselves. Females are the primary pollinators.

Not all bees are good pollinators. There is a rather large group of bees that don’t collect pollen and nectar for their offspring. They use pollen and nectar collected by other species to feed their young. We call these cleptoparasitic bees. They steal the food and part of the nests of other bees for their offspring. Parasitic bees make up about 10% of all bees.

Approximately 10% of bees are social [meaning they live in colonies in which workers do all of the foraging for food and queens reproduce]. These are honey bees, bumblebees, and a large group of bees that occur in tropical regions called stingless bees. Social bees are a minority, but they are very effective pollinators because they have very large colonies of workers that help them collect pollen.

About 80% of bee species are solitary. The female makes her own nest and she brings in food to provision the nest so she can rear her young. She is not assisted by any other individuals. She is a solitary bee and does all the work herself. When she is through provisioning the nest and laying her eggs, she dies. Her offspring appear the next year, after they mature.

Can you tell us about a few lesser known native bees in a couple of different parts of the world and some of the plants they pollinate?

Right now I’m working on a group of bees that tend to visit orchid plants in the New World tropics [Central and South America, the Caribbean Islands, and Mexico].

Called orchid bees, they are a tribe of five genera Euglossa, Eulaema, Eufriesea, Exaerete and Aglae. The latter two generas are parasitic, with the females laying eggs in the nests of other bee species, but the other three are solitary bees that go to orchid plants.

Euglossa sp.

Euglossa purpurea

These bees are a brilliant green or metallic red color, and they have very long mouth parts because they have to reach the nectary of the orchid. The males go the orchids to collect fragrances which they mix with a secretion that is derived from their hind legs to attract the female orchid bees.

I have also studied an interesting bee that was actually named after me: Xeromelissa rozeni. I discovered it in Chile. “Xero” refers to “dry,” and this bee lives in a very dry part of the Atacama Desert of Chile. It pollinates Nolana (Chilean bell flower). The bee has extremely long mouth parts, which it needs in order to reach the nectar inside the plant’s tiny, tubular flower. (By the way, in entomology and all of biology, we don’t go around naming animals after ourselves. I first picked up this bee in 1971. My colleague Dr. Haroldo Toro from Valparaíso University found other specimens of it and realized that it was not named. In the process of describing it, he validated this name for it.)

Xeromelisssa Rozeni using its long proboscis to sip nectar

In North America, where honey bees are not native, are they considered an invasive species? If so, what has their impact been on native bees in North America?

The word “invasive” usually has a connotation of something that is coming in and ruining the landscape. Honey bees are very important to us. There is no doubt that when it was first introduced here into North America, it greatly affected the other bees, because it was such a strong competitor for pollen and nectar. Since honey bees are very broad in their ability to collect and use pollen from wide range of plant species, they likely crowded out a lot of other bee species. So it was disruptive to native bees early on, but that wasn’t important to us then. There were plenty of bees in North America at the time, and our population was relatively small so they weren’t destructive to the food source of humans at that time.

When were honey bees introduced to North America?

They were clearly brought over by the early European settlers, likely for their wax for candles primarily, but also for honey as a source for food and alcohol (mead.)

Are honey bees still disruptive to native bees?

They probably are still disruptive to the native populations, but food requirements of our large human population requires our use of this species.

Speaking of honey bees, in 2015 alone, 40% of U.S. bee colonies “collapsed.” The term “colony collapse disorder” seems to be all over the news, in stories that are quite alarming. What is colony collapse disorder, and how much do we know about what causes it?

Colony collapse disorder is a sudden disappearance of the workers in a honey bee colony. The colony is left without workers to bring in food, and the queen bee is incapable of collecting food. We don’t know specifically why they disappear. It’s alarming. We rely upon honey bees to such a great extent for the pollination of so many crops in the U.S.

I think most people understand the importance of bees to our food supply. What can you tell us about the importance of bees in terrestrial ecosystems?

Bees are the foremost animal pollinators of plants. They are therefore the foremost pollinators of anything, except those plants that are pollinated by wind [or self-pollinated].

What do you consider to be the greatest threat to bee diversity?

Mankind’s altering of the landscape and the destruction of floral diversity caused by man. If you reduce the diversity of plants, you reduce the diversity of bees. That is a very serious problem. The ever increasing size of the human population is something to be very much concerned about.

What do we know about the impact climate change is having—and will have—on bees?

It can disrupt populations–not just because of temperature fluctuations but because the food sources will shift around. Widely fluctuating temperatures and precipitation patterns will cause disruptions. It is hard to anticipate what is going to happen, but the threat is there.

You have spent half a century studying bees, and you have traveled to more than 20 countries to do si. Is there a place in the world where bee diversity is thriving? Why?

There are many places where bees thrive because the populations are very speciose. Those areas are the semi-desert regions of the world. I have done a lot of work in places like the Atacama Desert of Chile and the southwestern part of the U.S., for example. These areas have a very rich bee fauna.

Dr. Rozen in the Atacama Desert in the 1970s

Interestingly, areas such as Arizona and New Mexico have a very rich bee fauna because there are two rainy seasons: the winter rain season, which brings on the spring flowers, and the summer monsoon period [which brings on different flowers]. In response to the monsoon rain, we have a very rich fauna of bees that has a different species composition from the spring fauna.

Do you have any pointers for ecologists, landscape architects, and others who want to create or restore habitat for bee pollinators in their planning and design work?

Diversity of plants is very important. That alone will help ensure a good return of bees visiting the landscapes. Sometimes it isn’t just the total number of individual bees you want but the diversity of bees. The only way you can really increase the diversity of bees is to offer them a broader range of kinds of plants. You want to include plants that flower at different times, have different shapes and colors. Knowledge of bees and their host plants is helpful.

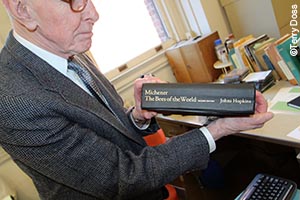

The most impressive book on bees, The Bees of the World, was written by my professor, Dr. Charles Michener. If people want to know more about bees—not only for information about their host plants, but for details about their life history and classification–that would be the book to have. It is an astounding book that was first published in 2000 [2nd edition published in 2007]. I understand Dr. Michael Engle at the University of Kansas is going to come out with another edition in a few years.

Any final words for Leaf Litter readers?

All I can say is something I found out a long time ago: bees are fascinating creatures and very important to mankind. Let’s hope that everyone takes care of bees by maintaining their diversity.

Editor’s note: After listening to Dr. Rozen’s tale of how he became interested in bees, I kept thinking back to that high school girlfriend of his. Who was she, and what ever happened to her? Well, her name was Barbara, and she ultimately became Dr. Rozen’s wife of many years. Though her career was in health care, she often assisted Dr. Rozen and accompanied him on field trips in the U.S. and abroad. In fact, he named a bee subspecies after her: Nomadopsis zebrata barbarae Rozen.