Peatlands of New Jersey: “Inexhaustible Stores of Fertility”

By Amy Nelson

About 15 years ago, while working to restore tidal marshes in the Meadowlands and researching fens of northern Alberta, I came across a copy of The Peats of New Jersey and Their Utilization, a report published by the State of New Jersey and Rutgers University in 1943. I haven’t worked in the Meadowlands in a while, and my hopes of finishing my PhD work on the Alberta fens are long gone, but I held on to this report as a reminder of how our views of natural resources, and specifically peatlands, have evolved over the years.

About 15 years ago, while working to restore tidal marshes in the Meadowlands and researching fens of northern Alberta, I came across a copy of The Peats of New Jersey and Their Utilization, a report published by the State of New Jersey and Rutgers University in 1943. I haven’t worked in the Meadowlands in a while, and my hopes of finishing my PhD work on the Alberta fens are long gone, but I held on to this report as a reminder of how our views of natural resources, and specifically peatlands, have evolved over the years.

A quick skim through this old report confirmed that even our very recent ancestors regarded peatlands as marginal wastelands that only had value because they could be reclaimed and used as fertilizers to improve agricultural land. And finding local sources became even more important during World War II, when the vast European sources of peat were no longer readily available.

From the report: “Because of the increasing density of the population and the close proximity of many of the bogs to large centers of population, the reclamation of many of the bogs deserves careful consideration on the part of both the conservationist and the agricultural economist.”

Thankfully, attitudes about peatlands have changed since the release of this study 75 years ago. We now value peatlands in their natural state for the ecological services they provide. We have a better understanding of the evolving nature of peatlands and the fundamental factors that influence the development of these systems – climate, soil and water.

But what about the peatlands themselves? How have the New Jersey peatlands surveyed in that old report evolved over the last 75 years? I was curious, and so with these papers and my camera in hand, I explored four very different New Jersey peatlands.

My first visit was to a cedar swamp located in the outer coastal plain of central New Jersey, in Wharton State Forest. On a hot, humid day I hiked through the blinding white sands of the Pinelands until I got to the cool, dark shade of a cedar swamp located along Skit Branch, an ecosystem known to have been relatively undisturbed over time. The soils in the area are generally sandy and acidic, and several kinds of pine and cedar trees thrive in these nutrient-poor soil. Within the cedar swamp, the soils are characterized as histosols, or peaty soils. The pools within the cedar swamp are dark brown, stained by the water’s high iron content.

In addition to the Atlantic white cedars (Chamaecyparis thyoides) dominant within the swamp, Sphagnum was found throughout.

According to the 1942-1943 paper, sphagnum was found throughout the bogs of this area but did not form peat. The peat resources found in this area are composed primarily of the remains of sedges, root and small stems. Sphagnum associations came too late in the bog development to contribute to the peat development typical of sphagnum bogs.

Although this site was relatively undisturbed, other ecosystems within the pinelands were impacted by early European settlement. In the 1700s and 1800s, peats were mined for by bog ore, filled and drained for farming, and trees cut for timber. However, over the past century, many of these impacted systems have been preserved and conserved as industry moved away from the area. As a result, many of these ecosystems have been slowly evolving to a more natural, undisturbed state and are protected and preserved. Active restoration of cranberry bogs throughout the Pinelands also continues to occur.

However, the peatlands of the Pinelands are still under threat as development pressures and demand for water increases, and as climate change alters precipitation patterns. Research has shown that the hydrological and ecological integrity of the groundwater reserves within the Pinelands is increasingly threatened. Any drawdown of the natural aquifers will threaten the flora and fauna species dependent on the remaining bogs.

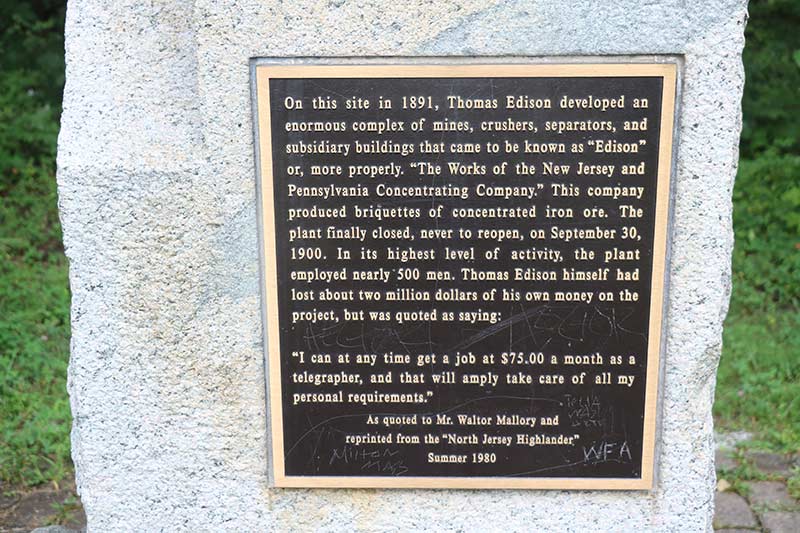

My next stop was to a relatively younger bog located in the New Jersey Highlands. This bog was created as a result of mining activities undertaken by Thomas Alva Edison, a famous New Jerseyan known for his many inventions. Less known were his mining technology inventions and his investment in a mining company on Sparta Mountain.

The mine was found to be not such a good investment and was closed in 1900. The escarpment created by the mining efforts inadvertently created bog habitat, now known as the Edison bog. Like the Pinelands, once industry left the area, the site was left to naturally recover, and the land is now preserved as part of the Sparta Wildlife Management Area.

Unlike the cedar swamps in the Pinelands, the vegetation is low within the Edison Bog, providing no shade and hot, buggy conditions in summer. The NJ Audubon staff that gave me a tour of the site let me know they don’t go into the site often because of the heat and insects in the summer. And in winter, because of the flowing water, the ice never freezes fully, creating unsafe conditions for traversing the bog.

Edison Bog is dominated by a diversity of species including heath shrubs, sedges and sphagnum moss, and is habitat for wading birds, songbirds, insects, mammals, reptiles and amphibian species. The forest habitat surrounding the bog is actively managed by NJ Audubon to create a more resilient forest canopy with a diversity of age and species.

A nearby bog in the Highlands, known as the Hyper Humus bog, was described in 1943 as:

“One of the most important bogs in NJ…. the Hyper-Humus… occupies an area of about 1,400 acres…. This peat deposit is on limestone in the great valley that extends across New Jersey from (the) Delaware River to the boundary line with New York State. Paulinskill River, draining to the Delaware, rises in this bog. The geology of the surrounding rocks is of considerable interest… Limestone knolls bound the bog to the southwest, and at the northeast is found a part of the Balesville recessional moraine, which was formed when the ice was in retreat and which has a maximum width of three-quarters of a mile. The moraine, laid down in the vicinity of Warbasse, dammed the waters of this part of the valley giving rise to a fairly deep lake, which, with the passage of time, became converted into a peat bog.”

The Hyper-Humus bog is named after the company which first started mining peat from the area in 1915. Mining operations continued until 1990 and left the site with little surficial peat. I visited the site, located in Sussex County close to the New York border on a cold and rainy day. A trail runs through the site, separating two large ponded areas west of the trail from the canal located east side of the trail. Because of the weather, I had the trail and the site to myself, along with a few large swans, a couple of egrets and a bunch of carp.

A number of invasive species have overtaken the site, including water chestnut (Trapa natans) and Eurasian milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) within the ponded areas, and common reed (Phragmites australis) in the area north of the pond.

Despite the destruction of the bog, the site includes the Hyper-Humus Fen Natural Heritage Priority Site, a limestone fen dominated by herbaceous and scrub-shrub vegetation. According to NJ Audubon, the limestone fen is a rare ecosystem with mineral-rich wetlands usually associated with limestone bedrock.

Despite the pervasiveness of invasive species, there is still a diversity of native plants lining the canal and ponds, providing habitat for a multitude of wildlife and avian species.

Efforts are underway to restore the meandering river and meadows that once ran through the site, as well as the trees which lined the river banks. These factors together likely created cooler water conditions, which support a greater diversity of native fish, invertebrate and plant species.

My last visit was to Mill Creek Marsh Trail in the Meadowlands. I’ve long been acquainted with Mill Creek Marsh – I was working on a nearby tidal marsh restoration project when this site was excavated in 1998 as part of a wetland restoration project being undertaken by the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission. During the excavation, stumps of Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides) were uncovered, reminding us of the site’s past.

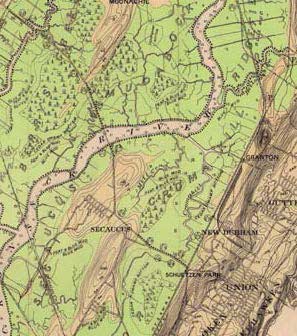

The Hackensack River and its adjacent wetlands were once freshwater systems dominated by swamps and bogs formed by glacial excavation and retreat over 15,000 years ago. Glacial Lake Hackensack persisted for several thousand years, and over time peat and muck built up on the lake sediments and glacial till. Studies that examined the Meadowlands’ peat and pollen records indicate a once rich peatland system dominated by sedges and rushes.

The area began to be settled by Europeans in the late 1600s, who diked and drained the peatlands for farming and development. A map developed by C.C. Vermeule in 1896 provides a snapshot of the conditions at that time, demonstrating that the Meadowlands were still a freshwater system with pockets of Atlantic white cedar, peat and muck.

According to the 1943 report, Vermeule presented the following description of the Hackensack meadows: “In its present condition, practically all of this area is unproductive. It raises a luxuriant crop of coarse sedge and salt grass having little value.”

Years later, after the headwaters of the Hackensack were dammed and a series of other hydrological changes occurred, what had once been a diverse freshwater system changed into a salt water system dominated by a monoculture of common reed (Phragmites australis). Peatlands that were cut off from inundation dried and subsided, and the landscape was forever changed.

The freshwater peatlands and cedar swamp once located at Mill Creek are long gone and can never be restored, but the excavation of the site created a unique habitat that attracts a diversity of aquatic life and birds, and the remaining cedar stumps create a primeval landscape that changes as the tide changes.

The wetlands within the site, now dominated by salt marsh cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) and a variety of other salt-tolerant plants along its slopes, continue to evolve and develop new stores of peat.

The narrow uplands built around the marsh are filled with pathways and a diversity of trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants.

The park at Mill Creek opens at dawn, which is usually the best time to get there. Adjacent to the NJ Turnpike and with NYC as the backdrop, it is never quiet in the pastoral sense, but early in the morning the site can feel remote and peaceful amid one of the most populous areas in New Jersey.

So, how have New Jersey peatlands evolved? I believe that, like most things in nature, there is no one answer. In general, they have responded in different ways to the various changes humans have imposed on them over the last 75 years. Some are entirely different ecosystems, some are still peatlands but different kind of peatlands, and a few are relatively unchanged. But all have ecological value and continue to face on-going threats from development pressures, invasive species, and climate change. And all are worthy of our attention and protection, and at times, restorative actions.

Otherwise, we end up with areas that have little to no ecological value, like this former peatland…