Expert Q&A

By Amy Nelson

Another example that can inform our thinking about the fourth generation of water is Singapore. For this city-state of over five million people it is not extreme weather that has driven them to think about their water supply; it is their national security. Singapore originally received its water from Malaysia. They weren’t comfortable with that arrangement, so they diversified their water portfolio so they’d be less reliant on a foreign country. They have pioneered what they call a “Four Taps” approach. They have the imported water supply, but also water recycling, desalination, and rainwater harvesting. Singapore has invested heavily in R&D on water technologies and has been an early adopter of new membrane treat technologies as well as a leader in efforts to make those technologies more energy efficient.

Those two cities are examples of places where the main driver has been an inadequate supply. In terms of managing too much water, the city of Philadelphia is serving as a laboratory for how to do green infrastructure for stormwater management. What particularly impresses me is the way in which the city is trying to integrate the efforts of the sanitation agencies with parks, zoning, and building departments to not only manage runoff, but make the city greener and more livable.

What Integrated Water Strategies do you think hold the most promise in terms of sustainable water management as we move into Water 4.0?

It’s one thing to read about the water crisis and water justice, or to hear mind-blowing factoids about water scarcity. It’s quite another to walk through a community that does not have access to safe drinking water or sanitation. To help make the water situation real to our readers, can you share an example of a community you have visited where people are being denied their right to water?

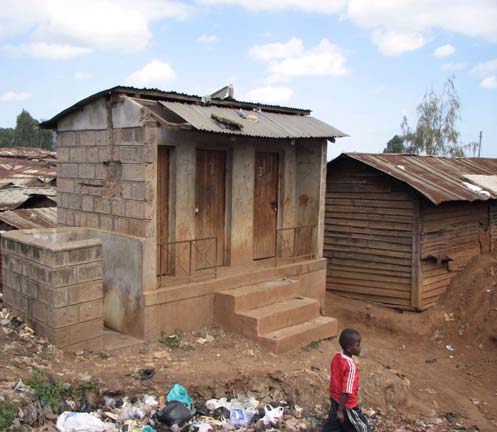

I have been in many communities without water. The one that haunts me the most is one of the world’s largest slums, Kibera, in Kenya. Almost one million people live in absolute poverty with almost no electricity and little running water, although a pipe from the local municipality has been recently been installed. There are no toilet facilities. Up to 50 shacks share a pit latrine (a hole in the ground) and local thugs often charge to use them. Local water surfaces are filthy, but people are forced to wash their dishes and clothes in them. The kids, of course, cannot bathe regularly so they have many related diseases.

In your book Blue Future: Protecting Water For People And The Planet Forever, you write: “There is no better example of a ‘runaway market engine’ than the corporate cartel now being created to own and profit from the planet’s supply of fresh water.” Is privatization/commoditization of water the biggest hurdle to protecting and locally managing water in a way that is both just and ecologically sustainable?

There are many hurdles to local, sustainable water systems. Sometimes there is not enough accessible clean water because a mining or energy operation has destroyed local waterways or the municipality dumps its sewage raw into river and lakes. Sometimes governments cannot afford to or choose not to deliver safe clean water to their people. And then sometimes a private company does in fact offer that service but charges tariffs out of reach of many families. So we insist that all people have the human right to safe, clean water and sanitation services delivered by a public agency on a not-for-profit -basis.

Despite the fact that the UN has, as of July 2010, recognized access to safe drinking water and sanitation as a basic human right, the UN is behind on its Millennium Development Goals related to this, particularly with regard to sanitation. (In Blue Future, you write that it will take till mid-century to provide ¾ of the world’s population with improved sanitation.) What does this lag in progress on sanitation mean for marginal populations? Is dependency on others for safe drinking water increasing due to ongoing contamination of local water resources?

The lack of progress on sanitation services for the poor is a major human rights issue. In fact, in my opinion, the lack of access to sanitation is the greatest human rights violation of our time, in terms of numbers of people affected. As millions are displaced from the land to make way for industrial free trade zones and land grabs, they migrate to the slums of mega cities where many have no access whatsoever to sanitation. In a world of such wealth, this reality speaks volumes about our priorities and our economic and social policies.

In this issue of Leaf Litter, we’re exploring the topic of “integrated water strategies”– ways of thinking about and dealing with water that integrate the built world with the natural world; people with the broader community of living things; and ecological science with architecture, planning, engineering, etc. Is there an example of an integrated water strategy you have seen implemented that really stands out in your mind as a success in terms of providing people, animals, plants, and downstream communities with access to clean water in a way that is sustainable? If so, can you tell us about it? (And do you have a photo you are willing to share?)

In Blue Future, I write about an engineer named Colin Pitman who greened a desert city in southern Australia by capturing rainwater, sewage water and grey water and cleaning it in natural lagoons and wetlands, and then storing it underground. The birds have returned to the wetlands, farmers have enough water to grow food and the city can even supply water for communities.

Many of our readers are water resources engineers (stormwater, wastewater, etc.), planners, architects, landscape architects, and environmental scientists. What is your vision for the future of water, and what role can people like our readers play in bringing it to life?

I call for a new water ethic that puts water at the center of our lives and all policy and practice if we and the planet are to survive. We need to protect water and restore watersheds in order to maintain healthy hydrologic cycles. We need to govern, not on the basis of political boundaries alone, but also on basis of watershed boundaries. We need to share watersheds to survive. I believe that water can be nature’s gift to teach us how to live more lightly on the earth and in better harmony with one another.

David Sedlak

David Sedlak is the Malozemoff Chair Professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of California at Berkeley, where he is co-Director of the Berkeley Water Center and Deputy Director of the NSF Engineering Research Center for the Reinvention of Urban Water Infrastructure. Much of his research addresses the fate and transport of organic contaminants in wastewater-impacted waters. David has served on numerous government advisory panels including the National Research Council’s Committee on Water Reuse and the EPA Science Advisory Board. He is an Associate Editor for the American Chemical Society journal, Environmental Science & Technology. In his book, “Water 4.0: The Past, Present and Future of the World’s Most Vital Resource” which was published in January, David examines three major revolutions in urban water systems over the last 2,500 years, and offers a hopeful window into the fourth.

When it comes to urban water systems, the combination of factors like aging infrastructure, increasing urbanization, and climate change, have brought us to the brink of what you call “Water 4.0”- a fourth phase of advancement in the way we manage water. Can you briefly summarize the first three phases for our readers?

It has often been said that water is the essential ingredient of life, and that is true from a biological standpoint. But when you look at the development of civilizations, water infrastructure is the essential ingredient of life. In the early days of civilization, when population densities were low, it was enough to have a well, or access to a stream or lake to acquire your water, and a dung pile or latrine to dispose of your waste. As cities got bigger, a different approach was needed.

When Rome’s population started approaching a half million, the local sources of water (the Tiber River and groundwater) weren’t enough to meet their needs. So the Romans applied engineering skills (and the ideas of many previous civilizations) to develop an imported water supply for the city. Their famous aqueducts are one obvious result. At the height of the Roman Empire, they were providing people with something like 100 gallons per person per day, which is equivalent to the water supply of many of our modern cities. The presence of all this water flowing into Rome, however, made it necessary to find a way to get rid of it when they were done with it. What were originally a series of drainage channels eventually got covered up and became the sewers of Rome. So the first generation of urban water systems (Water 1.0) was imported water coupled with sewers for disposal of waste.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, cities became smaller. In the second half of the 19th century, when the Industrial Revolution brought more people into cities, rapidly growing cities like London and Paris adopted the Roman approach to importing and disposing of water, but with a more modern twist: the inclusion of pressurized water delivery system. This created the preconditions for the second revolution in urban water. The outdoor latrine was replaced with the indoor water closet. Instead of disposing of human waste in a concentrated form in an outhouse, it was added to the water flowing through the sewers. Now, water flowing out of cities was contaminated with human waste. As cities became denser and people started to require their water supply from rivers contaminated by an upstream city, we had outbreaks of waterborne diseases like cholera and typhoid fever.

In the book, I use the cities of Lowell and Lawrence, Massachusetts, two textile-producing cities on the Merrimac River, to illustrate this problem and the eventual solution. Waste from all the workers in Lowell went into the river and became the water supply for Lawrence, which is located about 15 miles downstream. At the end of the 19th century, Lawrence experienced a very high incidence of typhoid fever. They couldn’t come up with another source of water, so the city turned to the engineers of MIT’s Lawrence Experimental Station. This led to the development of the sand filter. Within a decade, the technology of sand filtration was augmented with water chlorination. The one-two punch of filtering water through sand and adding chlorine was enough to make a sewage contaminated river drinkable. That second revolution in urban water, drinking water treatment (Water 2.0) quickly spread.

But people were still disposing waste from the sewer without any treatment at all, and this meant that downstream of cities, there were dead fish and terrible smells. That aesthetic insult was enough to make people want to do something, and in the early 20th century, engineers began developing sewage treatment plants. The two main technologies we have today—trickling filters and the activated sludge process—were developed at that time, but they weren’t applied very widely. Even after the Second World War, when population boomed, the rate at which sewage treatment plants were built was relatively slow. Eventually, pollution from inadequate sewage treatment led to widespread ecological problems. When the environmental movement finally came to a head in the early 1970s, the response that people had to all of the pollution resulted in a concerted effort to upgrade and improve sewage treatment plants. Even though many of the problems at the time were related to synthetic, organic chemicals, the main response was to invest in sewage treatment technologies. From 1972-1992, the federal government got involved in constructing and upgrading sewage treatment plants around the country, with the goal of making the nation’s waters fishable, swimmable, and drinkable. That was the third revolution in urban water (Water 3.0).

Let’s talk about Water 4.0. You write that “Perhaps the best long-term solution to our water problems will be to abandon centralized water systems altogether” and that doing this will require significant water conservation and reuse, as well as capturing and reusing runoff. You also predict that cities hit hardest by extreme weather patterns will become “laboratories where the rest of the manual for Water 4.0 will be written.” What city today is serving as the best, most hopeful laboratory?

Let’s talk about Water 4.0. You write that “Perhaps the best long-term solution to our water problems will be to abandon centralized water systems altogether” and that doing this will require significant water conservation and reuse, as well as capturing and reusing runoff. You also predict that cities hit hardest by extreme weather patterns will become “laboratories where the rest of the manual for Water 4.0 will be written.” What city today is serving as the best, most hopeful laboratory?

There are two visions of the fourth generation of urban water systems. One involves keeping our centralized systems and finding ways to make them more resilient. The other involves a radical change in the way we think about providing water services. The truth is, we’ll probably end up with a hybrid.

Let me tell you about three areas that are serving as living laboratories that will help us define solutions. The first, which might surprise some people, is Southern California. They have been experimenting with many new water technologies and investing in some pretty innovative approaches. Their early experiences are convincing us that water recycling is probably best done at a centralized scale, and done by cleaning the water to the point where it’s suitable for potable use. In the book, I describe the development of the potable water recycling systems in Orange County and Los Angeles. Another innovation from southern California is the idea of using urban stormwater runoff to recharge groundwater aquifers. Unlike previous efforts on the East Coast, Great Lakes, and Pacific Northwest, these efforts are not targeted at preventing combined sewer overflows; they’re targeted at capturing stormwater runoff, treating it, and using it for groundwater recharge. Southern California has also made great progress in water conservation and will continue to improve its water efficiency for the next few decades.

Another example that can inform our thinking about the fourth generation of water is Singapore. For this city-state of over five million people it is not extreme weather that has driven them to think about their water supply; it is their national security. Singapore originally received its water from Malaysia. They weren’t comfortable with that arrangement, so they diversified their water portfolio so they’d be less reliant on a foreign country. They have pioneered what they call a “Four Taps” approach. They have the imported water supply, but also water recycling, desalination, and rainwater harvesting. Singapore has invested heavily in R&D on water technologies and has been an early adopter of new membrane treat technologies as well as a leader in efforts to make those technologies more energy efficient.

Those two cities are examples of places where the main driver has been an inadequate supply. In terms of managing too much water, the city of Philadelphia is serving as a laboratory for how to do green infrastructure for stormwater management. What particularly impresses me is the way in which the city is trying to integrate the efforts of the sanitation agencies with parks, zoning, and building departments to not only manage runoff, but make the city greener and more livable.

What Integrated Water Strategies do you think hold the most promise in terms of sustainable water management as we move into Water 4.0?

One of the key attributes of Water 4.0 will be to make rivers and streams part of our water infrastructure and recognize that they’re not just conduits and flood control structures. An example is the Santa Ana River in southern California. Once an ephemeral river that flowed when snowmelt came down from mountains, it is now an effluent-dominant stream that carries the wastewater effluent from the Inland Empire’s four million people all the way to the Pacific Ocean. The river is something like 95% wastewater effluent, and it comes into the Prado Wetlands, a wetland complex run by the Orange County Water District which has been designed for enhanced de-nitrification. Those wetlands do more than just remove nitrate. They are an aesthetic feature, they provide habitat for a number of endangered species, and they are visited by birdwatchers and hunters. When the water leaves the wetlands, it flows back into the Santa Ana River, and downstream, gets routed out of the channel, recharges the aquifer, and becomes the water supply for people living in Orange County. So the Santa Ana River serves as a flood control channel, drinking water supply, and an aesthetic feature with habitat and recreational opportunities.

You are Deputy Director of the NSF Engineering Research Center for the Reinvention of Urban Water Infrastructure. Are there any new findings coming out of ReNUWIt related to integrated water strategies that you can share with us?

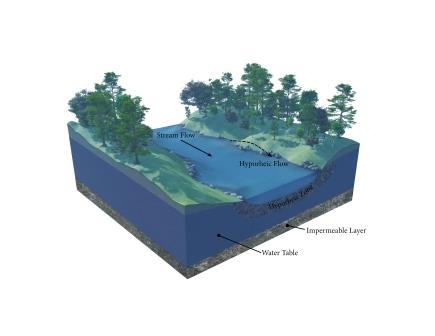

Much of what we are doing at ReNUWIt is related to integrated water strategies and this idea of seeing the natural environment as part of urban water infrastructure is one of our central principles. For example, one of my colleagues at Colorado School of Mines, John McCray, is working on a system to take advantage of the hyporheic zone in streams as a means to improve water quality. The hyporheic zone is where flowing water passes through stream or river sediments. It is a very interesting environment because it contains a high density of microbes that can remove chemical contaminants and can filter out waterborne pathogens. We already know that the hyporheic zone plays an important role in contaminant fate, but John is looking at ways of restoring or managing streams in ways that push more of the water into the hyporheic zone. That’s one example of a natural water system having a treatment function and integrating that treatment function into things like habitat restoration and flood control.

Many of our readers are water resources engineers, planners, architects, landscape architects, municipal government managers. Many are also environmental scientists. What can our readers learn from the “two thousand years of trial and error that went into Water 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0?

The greatest lesson from studying the history of the first 2,500 years of urban water systems is that change comes rapidly, and we had better be ready when society tells us it’s ready for change. These revolutions are frequently preceded by a few decades where people recognize that the existing system is no longer adequate and experiment with new approaches. They’re often frustrated that no one is willing to adopt them, but then one or two high profile events will happen, and in a very short period of time, the resources and political will exist to make a revolution happen. The lesson we can learn is not to be discouraged if it seems like people aren’t hearing our message. Eventually, the wisdom of doing something differently will be recognized and the resources will be made available to make it happen.

Paula Kehoe

Paula Kehoe is the Director of Water Resources for the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC). She is responsible for diversifying San Francisco’s local water supply portfolio through the development and implementation of conservation, groundwater, recycled water and desalination programs. Paula spearheaded the landmark legislation allowing for the collection, treatment and use of alternate water sources in buildings and districts within San Francisco. She believes integrated water management strategies are key to solving immediate and long-term water challenges and stresses that “whether it’s a stormwater, wastewater, or water supply challenge, we have to collectively address these issues.”

Where do most people in San Francisco think their water comes from, and where does it actually come from?

We manage a complex water supply system stretching from the Sierra to the City and featuring a series of reservoirs, tunnels, pipelines, and treatment systems. Two unique features of this system stand out: the drinking water provided is among the purest in the world; and the system for delivering that water is almost entirely gravity fed, requiring almost no fossil fuel consumption to move water from the mountains to San Francisco.

Most San Francisco residents are aware of our great tap water and they commonly call it “Hetch Hetchy water.” The Hetch Hetchy watershed, an area located in Yosemite National Park, provides approximately 85% of San Francisco’s total water needs. Spring snowmelt runs down the Tuolumne River and fills Hetch Hetchy, the largest reservoir in the Hetch Hetchy Regional Water System. This surface water in the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir is treated, but not filtered because it is of such high quality. The Alameda and Peninsula watersheds in the San Francisco Bay Area produce about 15% of the total water supply. The six reservoirs in the Alameda and Peninsula watersheds capture rain and local runoff.

We are the third largest municipal utility in California, serving 2.6 million residential, commercial, and industrial customers in the Bay Area. Approximately one-third of our delivered water goes to retail customers in San Francisco, while wholesale deliveries to 26 suburban agencies in Alameda, Santa Clara, and San Mateo counties comprise the other two-thirds.

Speaking of awareness…you previously served as public education director for San Francisco’s Water Pollution Prevention Program. What communication strategies and tools have proven to be the most effective in terms of getting people to think about water differently?

The most important element is really doing your homework and thinking through a number of critical steps. First, what are you trying to accomplish? Are you trying to inform or ask for someone to take a specific action? Next, you will need to determine who you are trying to reach to and to identify your “target audience”. Take time to learn more about your audience–conduct research, such as focus groups or surveys, to explore some of the real reasons behind people’s knowledge base or why they would take action so you can address those reasons in your public education campaign. Create effective messages that will appeal to your target audience and highlight the benefits of what you’re asking them to do. Finally, think about how to best reach your target audience and ways you to evaluate whether you’ve been effective.

Here’s an example . The SFPUC’s Water Pollution Prevention Program (WPPP), published Control It! Less-Toxic Methods to Control and Prevent Pests In and Around Your Home. Research conducted in the San Francisco Bay Area showed diazinon and chlorpyrifos in some Bay Area creeks and sewage treatment plant effluents at toxic levels. Diazinon and chlorpyrifos are broad spectrum pesticides commonly used to control structural type pests such as such as fleas, ants, cockroaches, termites and spiders. Approximately, 50-60% of diazinon used in California is unreported uses, like home and garden areas. Data also indicated that use and disposal of pesticides according to label instructions does not cause a problem. Therefore, the SFPUC developed Control It! to address the proper use and disposal of pesticides and recommendations of less-toxic methods to prevent potential water quality impairments. The activity was innovative because marketing strategies were used to design the book.

The book highlights the benefits to the reader by showing how to control and prevent pests, at the same time it addresses our concerns about water pollution. The book also contains colorful images to encourage residents to read about an undesirable topic such as household pests. The book was designed to provide critical information on proper use and disposal in an easy to read format so as not to overwhelm the reader. Finally, the book contains technically accurate images of pests which transforms the book into a resource guide—one to be kept and used time and time again. The SFPUC promoted Control It! in various ways. Advertisements were placed in the SFPUC utility bill (mailed to 165,000 SFPUC customers) and the SFPUC Water Quality Report (mailed to 320,000 residents). Mr. Handyperson, a nationally syndicated columnist, wrote a special article for the San Francisco Examiner praising Control It! “How much would you pay for this fine, useful brochure (Control It!)? $10? $20?” stated Mr. Handyperson. “He’s delighted to tell you it’s free,” exclaimed Mr. Handyperson. As a result of the marketing efforts, over 5,000 residents called to receive a copy of Control It! Additionally, local pest control operators have received copies for distribution to their customers. Control It! is part of a series developed for residents: Fix It! (automotive), Clean It! (cleaning products), Remodel It! (paint and paint related products) and Grow It! (garden pesticides products). The series has been extremely popular among residents and praised by the media—“If everyone followed the good advice in these helpful little brochures, this old town (San Francisco) would be a whole lot safer and cleaner,” stated Mr. Handyperson.

In 2012, San Francisco adopted an ordinance allowing for the collection, treatment, and reuse of alternate water sources for non-potable applications. How did that come about, and do you have any projections as to what portion of San Francisco’s water supply will come from this new source category in, say, 20 years?

We wanted to establish a program that would allow for and encourage the use of alternate water sources within buildings and districts for non-potable applications in San Francisco. We wanted to explore all types of alternate water sources including rainwater, stormwater, graywater, blackwater and foundation drainage and to encourage the collection, treatment and use of any of these sources as a way to reduce the consumption of potable water as well as to help to remove stormwater and rainwater out of our combined sewer system.

When we built our new SFPUC headquarters, we opted to include a treatment system that would treat all of the graywater and blackwater generated onsite. We incorporated the Living MachineTM, which is a series of engineered wetland cells, to treat the blackwater for toilet and urinal flushing in the building. We also included a rainwater harvesting system to capture water from the roof and child care center for irrigation purposes. We have reduced our use of potable water in the building by 65%. This is a significant water conservation measure, and is an enhancement to the It’s one of the only Living Machines that is actually in the public right-of-way.

When we were building our new headquarters, we also came across a number of developers interested in collecting, treating and using alternate water sources in their buildings. We all ran into the same questions- who regulates these systems? Who is responsible for ongoing monitoring and reporting to protect public health? What kind of water quality should be required for flushing toilets, irrigating landscapes?

We spent over a year researching and found that systems are on-line throughout the world, technologies exist, and water quality standards exist for certain alternate water sources. What we also found, was that in the absence of a clear process and lack of a regulatory framework it can create a significant barrier to implementation.

The SFPUC worked with our local Department of Public Health and Department of Building Inspection to create a program that permits on-site water treatment systems, requires ongoing monitoring and reporting, and establishes water quality standards to protect public health.

We formalized the program via ordinance. We started with the individual building scale and included a grant program. We will provide up to $250,000 for an individual building. A year later, we amended the ordinance to allow for district scale- more than 2 buildings to collect, treat and share and/or sell the water among building partners. We provide up to $500,000 for a district scale water system.

To date, we have over 20 projects proposing to collect alternate water sources. We have developed a report that details the projects in San Francisco, including data on costs, drivers and potable water offset. This data is informative to both the SFPUC and developers and architects. As we look to the future, we hope to see more on-site water treatment systems on-line in San Francisco. Information on our program can be found at sfwater.org/np

What would your advice be to other municipalities who want to create a similar ordinance in their city or region?

Your question is very timely. On May 29-30, 2014, representatives from state and municipal agencies from across North America gathered in San Francisco to discuss the critical issues associated with introducing and scaling on-site water treatment systems in cities across the country. The purpose of this meeting was to share knowledge and lessons learned in order to achieve our mutual goals of overcoming institutional barriers to on-site water reuse. It was a very inspiring meeting– to be in the same room with dedicated and motivated leaders who are on the forefront of on-site water treatment systems in places such as New York City, Seattle, Hawaii, and Minnesota. We all recognize that we need to continue to work together to establish programs that will allow these systems to be incorporated in our communities while ensuring we can protect public health.

As a next step from our meeting, we are preparing a guide to walk through the key steps that public agencies need to think about and do in order to programs in place to manage on-site water treatment systems in their communities. This “blueprint” will be ready and available to the public by September 2014. [Information will be posted on the San Francisco Public Utilities Web Site]

Another outcome from the meeting is a group of public health officials plan to work together and engage in a process to identify the most appropriate water quality standards and monitoring regimes for on-site water treatment systems. These guidelines will serve as a framework for local agencies to consider when developing on-site water treatment systems in their communities.

According to the US Drought Monitor, every single part of California is now facing “severe,” “extreme,” or “exceptional” drought and that the state is on track to suffer one of its worst droughts in 500 years. Are the state’s municipal water agencies working together to plan for longer-term drought?

Yes. The San Francisco PUC is a member of the Bay Area Regional Reliability Partnership, a partnership that includes six other Bay Area water utility providers. Collectively, we serve over six million residents, and thousands of businesses and industries. The partnership enables us to work together on near- and long-term water supply needs and look into working together to develop recycled water projects, conservation, changes in infrastructure, etc. We’re excited that this partnership has formed. Historically, water agencies have worked together and with this new partnership we have the potential to develop additional water supply projects on a larger, regional scale.

Any final words of advice for our readers?

Integrated water management strategies are key to solving our immediate and long-term water challenges. We cannot silo ourselves. Whether it’s a stormwater, wastewater, or water supply challenge, we have to collectively address these issues. It takes lots of champions to lead the effort and to create change. An integrated approach to water is hard work, but very rewarding.

Brian Richter

Brian Richter has been a global leader in water science and conservation for more than 25 years. As Director of Global Freshwater Strategies for The Nature Conservancy, Brian promotes sustainable water use and management with governments, corporations, and local communities. He is also the founder and President of Sustainable Waters, a global water organization focused on education and outreach related to water scarcity. Brian has served as a water advisor to some of the world’s largest corporations, investment banks, and the United Nations, and has testified before the U.S. Congress on multiple occasions. He also teaches a course on Water Sustainability at the University of Virginia. Brian has developed numerous scientific tools and methods to support river protection and restoration efforts, including the Indicators of Hydrologic Alteration software that is being used by water managers and scientists worldwide. Brian was featured in a BBC documentary with David Attenborough on “How Many People Can Live on Planet Earth?” He has published many scientific papers on the importance of ecologically sustainable water management in international science journals, and co-authored a book with Sandra Postel entitled Rivers for Life: Managing Water for People and Nature (Island Press, 2003). His new book, Chasing Water: A Guide for Moving from Scarcity to Sustainability, will be published by Island Press in June 2014.

We’re exploring the topic of “integrated water strategies,” ways of thinking about and dealing with water that integrate the built environment with the natural world; people with the broader community of living things; and ecological science with architecture, planning, engineering, etc. Is there one example that stands out in your mind of a real, implemented, integrated water strategy that is working, in terms of providing people, animals, plants, and downstream communities with access to clean water in a way that is sustainable?

Yes: the community of water users and government entities in the Murray-Darling River Basin of Australia. Certain elements are essential to a water success story. First, there has to be sufficient investment in the collection, analysis and communication of data. Second is the inclusion of environmental considerations. There are natural processes in the watershed that provide tremendous water services to society, but at the same time, there are habitats and ecosystems that require water themselves in order to be sustained in a healthy condition. When managing water, we have to be thinking about those ecological water needs. The last element, and the one that has been the most extraordinary in the Murray-Darling Basin over the last two decades, is the recognition that there are, ultimately, limits on resource availability and we have to live within those limits. At both the state and Commonwealth level of government, Australia has put forth a great deal of funding ($12 billion from the commonwealth alone) to help local communities reduce their water use to a within a more sustainable limit, while leaving enough water for ecological support. They did this three ways: urban water conservation, agricultural irrigation efficiency improvements, and the buying back of water rights from willing sellers.

Towns that depend on water coming out of the Murray Darling Basin made phenomenal progress in reducing water consumption. Local city water managers provided incentives and mandates, and many cities cut their use by 30-50%.

The vast majority of the water used in that basin goes to agriculture. Of the $12 billion from the Commonwealth government, roughly $8 billion is being directed toward enabling farmers to invest in advanced technologies and more efficient equipment so they can substantially cut their water use. The farmer pictured to the right, Howard Jones, grows wine grapes using drip irrigation. He is the board chair for the Murray-Darling Wetlands Working Group.

All large water users [in the Murray-Darling Basin] have to have a water right, an entitlement to use a specified volume of water. The Commonwealth government offered to buy water rights from willing sellers. Many were farmers who didn’t need all of the water to which they had rights. This “buy back” reduces water use, so more water remains available for ecological support. That provided a huge stimulus for conservation.

You work with ecosystems, communities, corporations, and investment banks. How do you balance the water needs of businesses and organizations with the water needs and rights of all people, as well as the animals and plants who do not have voices?

It’s important to start by doing what you can to make everyone aware of what is at risk if water isn’t used and managed well. Only a very small portion of the population has any awareness of how their water use can compromise other things that they value (biodiversity, recreation, agriculture, etc.). It’s important to empower those who can speak to those values and to provide them with access to the decision making process. In the developing regions of the world, a very significant part of the human population is still very directly dependent upon ecosystems for their livelihood and survival. For example, we estimate that there are at least two billion people who derive much of their food supply directly from river ecosystems and estuaries. Those people should have access to the dialogue and decision making process.

We have to make everybody aware of the value of natural systems and how people depend upon them, but we have to supplement that with speaking to corporate bottom lines and reputations. If water isn’t managed well, there won’t be enough water for everyone, including people who manufacture products or grow agricultural goods. If you impact local people or ecosystems, it can really damage your reputation and your brand.

We are an active participant in the United Nations CEO Water Mandate, a forum that the UN created to bring corporate leaders together with NGOs to have a more open, frank, and productive dialogue. We also try to inform the development of sustainability standards.

We have found it to be most productive when we can help both a company and community of water users understand the challenge they face together. One illustration is General Mills. We began by looking at where they have processing plants and where they buy agricultural products. We mapped it out, looked at how their corporate distribution compared with what we knew about water scarcity, and honed in on real communities and ecosystems that were being impacted. This encouraged the company to engage with the communities with whom they shared water resources. General Mills has since provided grants to some of their famers to help them install more water-efficient equipment. It’s through that kind of very real, local, and personal dialogue between communities and companies that we have the greatest hope of being able to move in a productive direction.

You have cited Israel and Australia as examples of countries that live within a water budget much better than we do here in the U.S. Tell us about some of the strategies for successfully working within a water budget.

I often use the analogy of our personal bank accounts. If you keep withdrawing more than you’re depositing, you’re going to get into trouble. With water, it’s a shared bank account, and a lot of people have access to it. In your budget, you have to make sure you open up the dialogue to the full range of interests. You have to hear them out, give their values and concerns due consideration, and then find a way–as a community–to talk about who gets how much, and how you will protect everyone’s values, including ecological values.

When people understand how much water is available, they then understand that with any new use (growth in industry, energy development, etc.) there will be a tradeoff, because it’s a bank account. If you let a new expenditure come in, you have to cut back on something. Unfortunately, debates about issues like fracking, which tend to polarize, take place without that context. Water budgets allow for much more informed decision making.

A good example is Texas. There isn’t a lot of water to begin with, and the state is growing rapidly. They used to do water planning at the state government level, with little to no interaction with local communities. When they hit a bad drought in the late 1990s, and the State proposed various remedial solutions, a lot of the local communities said, “We don’t think that’s the smartest way to deal with these problems. We think we should try X and Y.” To their credit, the State heard that and massively reformed the way they plan for their water futures. They formed 16 regional planning groups, largely organized around Texas’ major river basins. By legislative mandate, these groups, each with 20-30 formal members, represent all interests: agriculture, industry, power, mining, environmental values, etc. All of these people come together around a table, hash it out, and recommend strategies to the state.

The Nature Conservancy championed stakeholder engagement in Texas, and in the early 2000s, we collaborated with other environmental organizations in the state and made a strong case for including ecological water needs in the water budget. A bill passed in Texas last year that will provide $2 billion for implementation of regional water plans. Twenty percent of that got earmarked explicitly for conservation. We’re also contributing guidelines for the rest of the $2 billion, so that you don’t get to access that money to build a new reservoir, pipeline, or desalination plant unless you meet some water conservation standards first.

Do you think there is one ideal scale at which integrated water strategies can be the most effective?

Organizing around an individual water source makes a great deal of sense. Here’s an interesting tidbit. Back in the 1800s, John Wesley Powell, famous for leading the first expeditionary team down the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, was the first director of the U.S. Geological Survey. As the West was developing, he encouraged societal leaders to think about organizing politically around watershed boundaries. He envisioned states or counties as being watershed units. Instead, we ended up with state governments with all these different agencies that may have something to do with water, but have very little interaction with each other.

Regarding scale: organize as small as you can, because you want every stakeholder with a concern over water to have a voice, or at least representation. If you get too big, you really lose that. On the other hand, you have to organize in a way that’s large enough to get at the nature of the problem. If you’re talking about the fact that too much nitrogen is flowing down the Mississippi River and causing a dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, then in some way, you have to facilitate a decision-making process that includes all of the states that are contributing to that problem. The key here is a nested dialogue. It’s not easy. As you cross political boundaries, complications go up exponentially.

Tell me about your new book, Chasing Water, and the main thing you want readers to come away from it knowing/thinking/doing.

The motivation for this book was to try to build water literacy from the ground up. I realized that if I was going to be such a big champion of local water democracies, then we have to make sure that we have an informed citizenry. It’s one thing to open up the doors of democracy to broader participation; it’s another thing to have an informed conversation. There is abundant evidence to suggest that we have widespread water illiteracy in the United States and throughout the world. The Nature Conservancy did a research poll and found that nearly 80% of Americans have absolutely no idea where their water comes from.

The motivation for this book was to try to build water literacy from the ground up. I realized that if I was going to be such a big champion of local water democracies, then we have to make sure that we have an informed citizenry. It’s one thing to open up the doors of democracy to broader participation; it’s another thing to have an informed conversation. There is abundant evidence to suggest that we have widespread water illiteracy in the United States and throughout the world. The Nature Conservancy did a research poll and found that nearly 80% of Americans have absolutely no idea where their water comes from.

Another goal for me is to communicate that living sustainably shouldn’t be just a utopian dream or a slogan. With respect to water, I want people to know that sustainability is well within our reach, but we cannot continue to assume that someone else is going to take care of that for us. We can’t assume that our governments have this under control. No government anywhere is managing water in a way that is optimal or sustainable. It’s important for us all to take personal responsibility for water. We need to know where it comes from and what happens when we’re not managing it well. Then, we need to inspire our broader communities and governments to do a better job.