Expert Q&A: Dr. Susan Clayton

By Amy Nelson

What is the state of the science today on the connection between a healthy environment and human health and well-being?

What is the state of the science today on the connection between a healthy environment and human health and well-being?

We have pretty good evidence that there is a connection at all kinds of levels. We have not yet gotten enough specificity, however, when it comes to understanding how much exposure is needed to make a difference and what counts as nature. Is it good enough to have a picture of a forest in your room, for example?

What is the best way for people to find research related to this connection?

A lot of people in different professions are recognizing that they need to learn from other specialists, but finding information is not always easy. There are, however, an increasing number of journals that are problem-focused (climate change, sustainability, etc.), rather than disciplinarily based, so that is one place to look. Social media is another. There are certain organizations that try to make their information available to a wide audience through news feeds on Twitter and Facebook. The Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues is a great example. Their goal is to publicize good, solid psychological research that is relevant to social issues.

You are a member of the American Psychological Association’s (APA) Task Force on the Interface between Psychology & Global Climate Change. In 2009, you and other task force members presented a report to the APA which considered psychology’s contributions to climate change by addressing six specific questions. One of the questions explored was “What are the human behavioral contributions to climate change and the psychological and contextual drivers of these contributions?” What can psychology tell us about the drivers of consumption?

Psychologists have been examining this question for decades, which is a long time in this area. There are different kinds of behaviors [related to consumption]. Some involve deciding to do less—to curtail one’s own use of resources. Others are about choosing different kinds of behaviors—walk rather than drive, or eat organic food, for example. Others involve one-time decisions, often about a purchase of some technology.

Different factors affect those behaviors. Certainly there are stable, long-term influences on our behavior, such as values, knowledge (understanding environmental challenges and how your behaviors relate to those challenges), and one’s own sense of a personal involvement with the natural world. But in any given instance, the things that are more important [in influencing behavior] are very immediate, like incentives (the costs or benefits of certain behaviors), prompts, and reminders. Design of the physical environment can be very important. For example, if there is a recycling bin right next to the mail room, you’ll recycle your mail. If there isn’t one, recycling will drop down. One of the strongest impacts on behavior is social modeling—what you see other people doing.

John Fraser used the phrase “human addiction to overconsumption.” Should practitioners of conservation planning, ecological restoration and regenerative design think of themselves as interventionists? If so, what wisdom can they take from psychology as they try to break people of this addiction?

People often wonder why people do things that harm the environment. Thinking of environmentally harmful behavior in the same way we think of personally harmful behavior, like smoking or overeating, can be useful. Many people want to quit smoking, but need help to do it. Many people might want to behave in a more environmentally sustainable way, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy to do.

Here’s one example of what we can learn from the models of clinical intervention. [In the late 1970s, researchers] James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente at the University of Rhode Island came up with the Stages of Change Model, which addresses this question: “Where is the person in terms of considering a lifestyle change?” Assuming that a change is desirable, how is a person thinking about this change? Have they just started thinking about it? Do they recognize a change needs to be made? Maybe they vaguely know that they need to make a change but they have no plan yet. Perhaps they’ve already made the change but they need encouragement to help sustain it. Understanding where people are in terms of thinking about a desired change affects they way you try work with people.

The aim of the APA Task Force report was to engage psychologists in the issue of climate change. Has there been progress in this regard in the five years since the report came out?

Yes. There has been a lot more research, a few new journals, and in existing journals, there has been much more research on this topic. There is definitely room to continue to progress, but psychologists now have a much greater awareness that this is a topic that is relevant to them, and that they should be involved with it. This past summer, I was involved with another APA report on the psychological impacts of climate change. The fact that the APA chose to co-sponsor this effort [along with ecoAmerica] shows how important this issue is to them as an organization.

An increase in research is great. What about the amount of collaboration between psychologists and those working in other disciplines on this issue?

There is a growing awareness that this is an issue that requires people to cross disciplinary boundaries. It’s difficult to have an objective assessment of this, but I see many more examples of multi-disciplinary working groups that are designed to address specific challenges. I see this particularly in the UK and Germany, where there are even government sponsored institutes or working groups.

For example, the European Commission recently sponsored a conference on “Renaturing Cities: Research and Innovation Policy Priorities for Systemic Urban Governance,” held in Milan, Italy. The UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs has a Social Science Expert Panel to advise them on projects to protect the environment. I also see it in my own experience. People who are not psychologists have reached out to me, and I have participated in a number of workshops designed to bring together people from different disciplines. For example, I was invited to be part of a group from the education field that was defining what environmental literacy might mean. A biologist colleague of mine reached out to me because she wanted to understand more about the psychology behind how people react to biodiversity in an urban context. We have been working together on that project for a few years.

Can you tell us more about that project?

We are working within zoos, because in urban settings, zoos typically offer opportunities for urban residents to confront nature and learn about biodiversity. We’re looking at what happens in the course of a zoo visit and how that could be made to be a more effective way of reaching out to people and engaging them with the issue of threats to biodiversity.

Speaking of zoos…in your paper, “Psychological science, conservation, and environmental sustainability,” which appeared in the journal Frontiers in Ecology last year, you highlighted the “Seal the Loop” program, initiated by Zoos Victoria (a zoo-based conservation organization in Australia), as an example of a successful collaboration involving psychologists and conservation professionals. Can you tell us a bit about this program, and how psychology is being applied to it?

My co-author, Carla Litchfield, was personally involved in that program, which attempted to apply important psychological principles toward participation in a conservation initiative [preventing seal deaths resulting from entanglement in discarded fishing line]. The idea was to get people to properly dispose of fishing line. In the zoo setting, they used the emotional hook to generate an empathic reaction to seals. This then motivates them to care more about this issue. [The project also involved the installation of 184 disposal bins near popular angling spots along Victorian beaches and waterways.] They also monitored the program carefully to assess its effectiveness. So psychology was involved in this project in three ways: thinking about the role of the emotional response to the seal and how that could be a selling point for changing behavior; thinking about making the desired behavior very public so that it becomes the norm; and assessing the program scientifically.

The paper in Frontiers in Ecology includes principles for effective application of psychological science in conservation and sustainability. One of those principles is to “work with architects and engineers to develop and test simple design modifications.” Can you elaborate?

There is a “human factors” approach, which asks: what physical changes can you make in the built or designed environment that might reduce people’s energy use? For example, can make stairways more inviting so people choose them over the elevator? These things do not have an effect in and of themselves, like energy efficiency, but they affect human behavior. They encourage people to behave in a way that reduces the use of natural resources. I have seen some green design criticized for focusing on the way the site was constructed but not focusing enough on the way it is actually used.

Susie Burke of the Australian Psychological Society, talked about the importance of appealing to intrinsic values when it comes to behavior change to improve the natural environment. You, too, say (in the same article) that “Changing people’s minds may not be necessary. Rather, given that most people value the natural environment, effective behavior change may only need to highlight these values.” Can you talk about the psychological evidence that people actually care about nature and really do have motivation that is pro-social and transcendent?

People often have an unduly pessimistic view of human nature. There are plenty of examples—with regard to environmental issues and in other domains—showing that people often act very altruistically for reasons other than self interest. There are many surveys in which people talk about how important the environment is to them, Willett M. Kempton (1995) found that most Americans viewed nature as having a moral component, something that has also been suggested by P.H. Kahn’s research. The Yale Project on Climate Change Communicationhas data showing overall support for environmental protection. These articles [also address this issue]: Markowitz, E.M. (2012). Is climate change an ethical issue? Exploring young adults’ beliefs about climate and morality. Climatic Change, 114, 479-495. Markowitz, E.M. & Bowerman, T. (2012). How much is too much? Examining the public’s beliefs about consumption. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 12, 167-189.

When asked, people often say that taking care of the environment is a moral issue. They recognize that it’s not just discretionary; it’s a responsibility. A lot of my own work has to do with people’s sense of personal relationship with the environment, and I tend to find high levels of people saying, in a variety of ways, that the environment is important to them, and that if they weren’t able to spend time in nature, they’d feel like something was missing in their lives. There is also interesting research on people’s experience of awe and transcendence. Those sorts of experiences seem to be more likely to occur in natural settings, and they involve strong, powerful, emotional responses. [SEE the section entitled “Wild Nature and Spiritual Experience” in Susan’s book CONSERVATION PSYCHOLOGY: Understanding and Promoting Human Care for Nature] Recent research has actually suggested that in some cases, nature can actually inspire people to act better. It brings out the best in us and encourages people to be more altruistic, for example.

You advise conservation practitioners not to rely on intuition and assumptions when it comes to human behavior, but to access relevant psychological research. Are there common misconceptions about human behavior that are made by conservation practitioners? What are they?

My context for this is a perception, and it may be unfair in some cases, but I feel like very informed scientists, who would never think of making assumptions about other species without testing them, somehow assume that they don’t need evidence to jump to conclusions about human behavior. We think we know about humans, but we don’t.

The most broad misconception people fall prey to is the idea that human behavior is rational. People are motivated by things that might involve a careful cost/benefit analysis (economics, time, etc.), but most of the things we do, we do automatically, without even thinking about them. We do them out of habit, or because other people are doing them. Recognizing the sources of influence on human behavior that are operating outside rational awareness is important.

In the policy arena, there is an assumption that the best way to motivate people is to provide financial motivations. Sometimes financial motivations can actually be counterproductive, by changing the way people think about an issue. When you encourage people to think about the financial side of something, they may stop thinking about the moral or ethical side. So stressing money can have a reverse effect from the one intended.

In addition to being aware of those major misconceptions, can you offer any other pointers to help people avoid paradoxical effects like that?

Be aware that people do not like to be told what to do. Any attempt to change behavior that too overtly controls their behavior may have a backlash effect by motivating people to resist. A colleague of mine gave an example. When recycling was instituted in his community, people went to great lengths to not recycle, and to demonstrate that they were not recycling, because they didn’t like the idea that they were being forced to do something. By now, recycling is the norm, so we don’t see that.

Sometimes actions that are designed to address a problem can actually motivate people to behave in a way that makes the problem worse. When people think a problem is being taken care of, they may think they don’t have to do anything about it, and they may behave in a way that increases the problem. A classic example is when an extra lane is added to a highway. That usually ends up making traffic worse because people think “Oh, there are more lanes now, so I can definitely take the highway!”

One of your suggestions for fostering more collaboration among behavioral and natural scientists is to craft papers written for a broad audience and for cross-disciplinary, problem-focused workshops and conferences. Are there any particular conferences you’d recommend our readers check out?

Two that come immediately to mind are the Behavior, Energy, and Climate Change Conference and the Energy and Climate Change Conference.

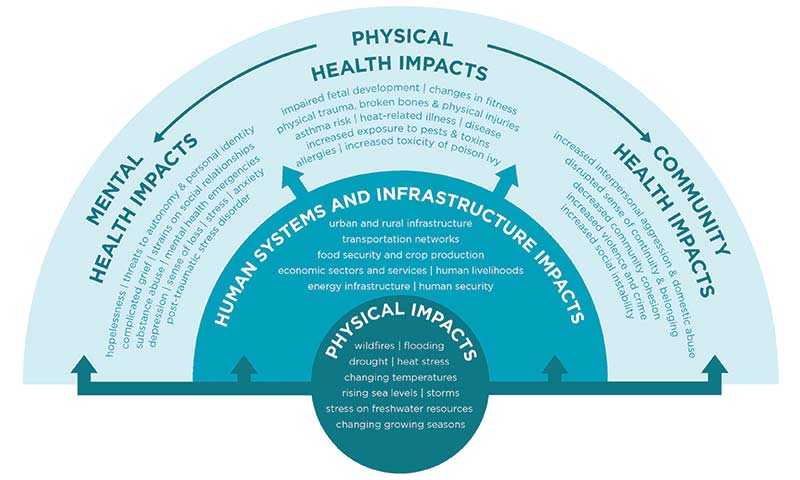

As part of a collaborative project with the APA and ecoAmerica, you recently co-wrote a report on the physical, human, and mental health impacts of climate change. (Beyond Storms & Droughts: The Psychological Impacts of Climate Change) Can you talk us through the graphic that appears on pg. 12 of the report? (Note: a webinar on this report is available here)

A lot of people don’t think of climate change as having psychological impacts. What we were trying to show in the report and with this graphic was how psychological impacts do happen, and how we know what they are. It is difficult to point to a specific [psychological condition] and attribute it to climate change. What we have to do instead is take the physical impacts we know climate change will have based on what the climate scientists say. These are things like flooding, drought, wildfires, and change in temperatures. Then, we ask what are the effects of those physical impacts will be. We look at both community and societal basis, in terms of infrastructure. That includes things like food production, energy, and transportation networks—the kinds of things the Pentagon [looks into]. In fact, the U.S. Department of Defense recently released a report about threats to infrastructure that will result from climate change, and why it’s relevant to national security. Based on those kinds of one-level-up effects, we look at how they might affect human psychology, well-being, and social interactions.

We didn’t make a hard and fast defining line between physical and mental health, but clearly some effects are more physical and some more mental. They both occur within this context of community/societal health, and they are interdependent. Mental health impacts, like depression, anxiety, strains on social relationships will certainly be affected by physical trauma, community impacts like increased violence and social instability.

We didn’t make a hard and fast defining line between physical and mental health, but clearly some effects are more physical and some more mental. They both occur within this context of community/societal health, and they are interdependent. Mental health impacts, like depression, anxiety, strains on social relationships will certainly be affected by physical trauma, community impacts like increased violence and social instability.

Seeing all of these impacts—from increased toxicity in poison ivy to increased domestic abuse–in one image was very powerful.

Those are such specific things, but they do help you think about climate change in a different way.

How can knowledge related to the psychological impact of climate change help inform the work of our readers, many of whom are practitioners in ecological restoration, conservation planning, and green design?

The ways in which green design is defined can vary greatly, so it’s hard to make a blanket statement, but the knowledge that changing climates are going to have psychological impacts can provide the extra motivation or impetus to think about ways to address them in design. There is some evidence that green design can compensate in some ways to lack of access to nature and might actually motivate people to feel more connected to the natural world and therefore possibly motivate greater concern. This evidence of the psychological impacts of climate change can be a motivating factor for design. It may also suggest some possible things to include as part of design. With ecological restoration, for example, it might lead a designer to think about ways to incorporate community participation. Depending on what the restoration is designed to do, that may make it more effective with more community buy-in, but it can also be helpful to the community to feel like they are doing something positive [in the face of climate change]. Giving people a sense that there are ways to address environmental problems can help combat the hopelessness that many people feel.

The ways in which green design is defined can vary greatly, so it’s hard to make a blanket statement, but the knowledge that changing climates are going to have psychological impacts can provide the extra motivation or impetus to think about ways to address them in design. There is some evidence that green design can compensate in some ways to lack of access to nature and might actually motivate people to feel more connected to the natural world and therefore possibly motivate greater concern. This evidence of the psychological impacts of climate change can be a motivating factor for design. It may also suggest some possible things to include as part of design. With ecological restoration, for example, it might lead a designer to think about ways to incorporate community participation. Depending on what the restoration is designed to do, that may make it more effective with more community buy-in, but it can also be helpful to the community to feel like they are doing something positive [in the face of climate change]. Giving people a sense that there are ways to address environmental problems can help combat the hopelessness that many people feel.

The goals of the paper were not only to prepare planners, policymakers, health officials, but to “bolster public engagement around climate change.” John Fraser discussed the need to make climate change a more proximal concern without completely freaking everyone out or paralyzing them. Is this an attempt to do that? Are psychological impacts something more people can more readily imagine or relate to?

Absolutely. That was very much part of what motivated the report. We know that climate change can seem like a very distant issue for a lot of people, and we know that personal relevance makes people pay attention more. To gather this information in one place and be able to show, through specific cases and narratives, that climate change is happening now and is going to affect people like you, helps bring it to the front of the mind and makes it easier for people to relate to it.

Given what you do, you are not only aware of the degradation we humans have caused to the environment, but the many psychological barriers to necessary behavior change. What keeps you from throwing in the towel? How do you stay hopeful?

There are certainly times when I feel pessimistic, but for me, it comes down to creating meaning and purpose in my life. Think about the things we can do as individuals, and the opportunities we have to do things we think are important. Those same opportunities exist for us as a society, to re-examine our priorities and redesign the standard operating procedure. Bad things happen, but the process of working on something that is important can give you a profound sense of purpose that can counteract pessimism and hopelessness.