Trekking Across Alaska: A new vision for a changing landscape

By Amy Nelson

What was only supposed to last 20-30 years has continued to transport oil for 40 years. However, it is not as busy as it once was. Oil production, which peaked in 1988 at two million barrels a day, is now around 500,000 barrels a day. Oil demands continue to weaken as the country and the world look to alternative sources of energy.

The pipeline has also become increasingly costly to maintain. The very success of the pipeline to facilitate fuel extraction and use has, in a fitting turn of fate, accelerated the rate of climate change and global warming, and weakened the very foundation on which the pipeline was built. Arctic areas have seen some of the most dramatic temperature shifts due to climate change.

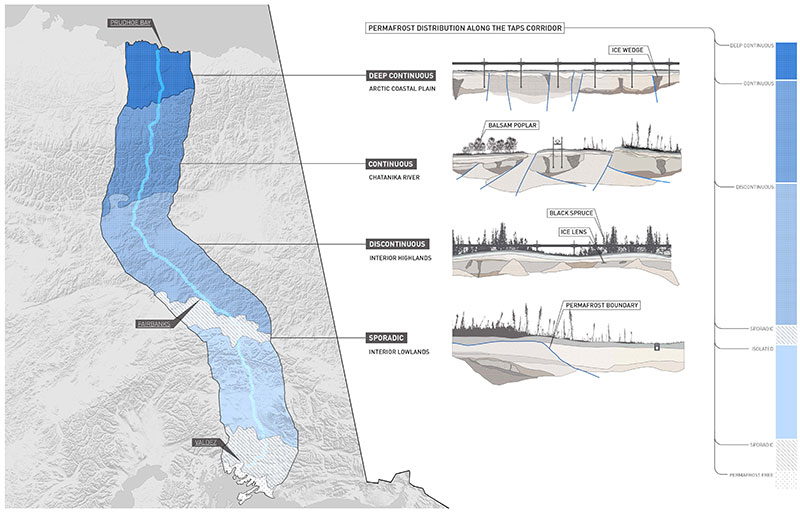

In Alaska, the average annual temperature has increased by 3°F, and winter temperatures have increased by 6°F. As these temperatures continue to rise, permafrost that blankets much of the land north of the Arctic Circle is at risk of thawing. As it thaws, it will become more like a bog than solid ground. While the pipeline was designed to withstand many environmental factors, one factor not planned for was hundreds of miles of the “silver snake” sinking and bending as the ground beneath it collapses.

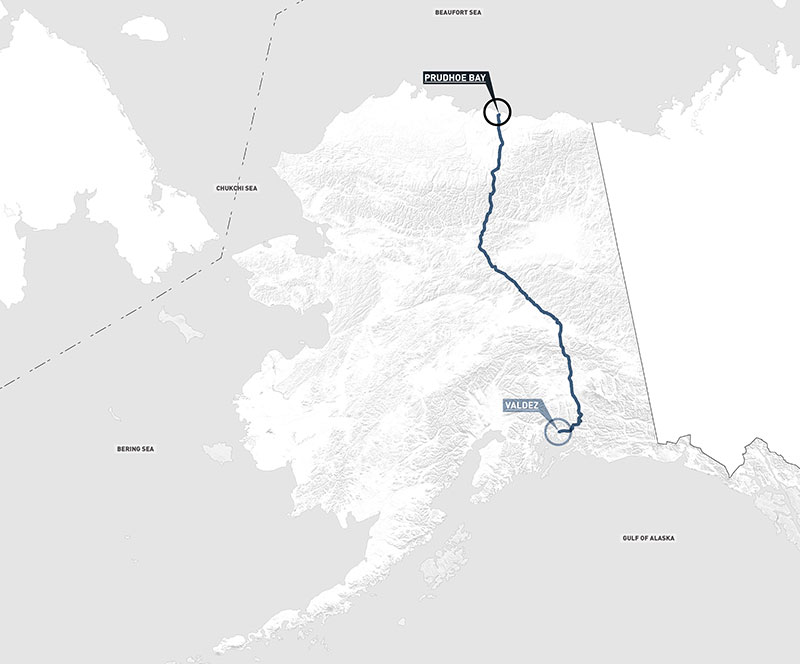

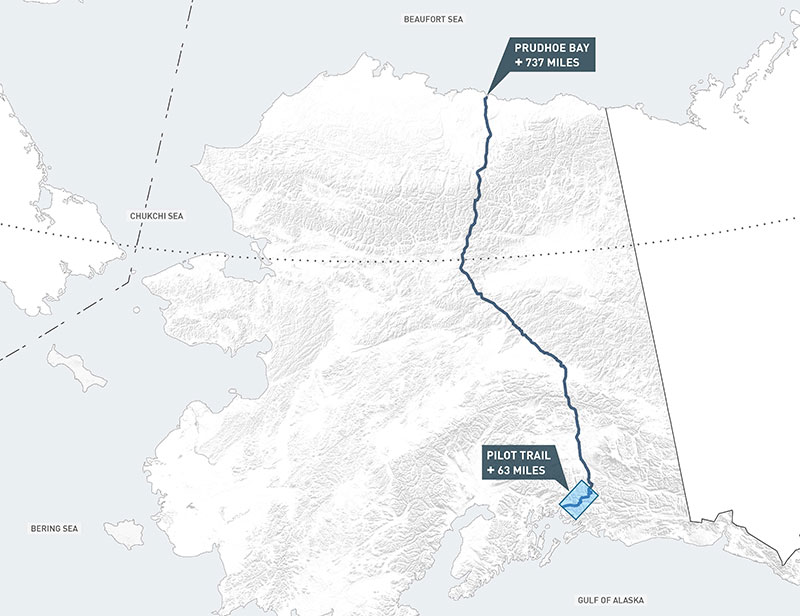

Given global changes in consumption, some leaders in the state of Alaska have begun investigating what an alternative future would look like. One scenario involves a boon for eco/adventure tourism and outdoor recreation, and a new future for the pipeline: the Trans-Alaska Trail. It would be Alaska’s own long-distance, recreational trail. Similar to the Pacific Coast Trail or the Appalachian Trail, the Trans-Alaska Trail would weave its way through the wilds and wonders of the Alaskan interior.

Championed by State Rep Jonathan Kreiss-Tomkins (D-Sitka), a marathon and long-distance trail runner who has run various lengths of the pipeline in the past, the Trans-Alaska Trail would follow the 4′x4′ maintenance track that runs parallel to the pipeline. Presently the route is already available for recreational use on a case-by-case basis, through permissions authorized by the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company, a consortium of oil companies that owns the pipeline and controls access to a 100′ easement on either side of it. But Representative Kneiss-Tomkins envisions this trail as a multi-use, public tourist destination and a new source of income for Alaska. In recent media, the trail has been billed as a “world class outdoor recreation destination and high octane additive for Alaska’s rapidly developing adventure tourism economy.”

Landscape architects Katherine Jenkins and Parker Sutton, who teach at Ohio State University, met Kneiss-Tomkins during their first trip to Alaska for their graduate research in 2014. They had chosen the Trans-Alaska Pipeline as the centerpiece of their work because they were interested in the sheer magnitude of this manmade infrastructure and its place in the Alaskan landscape. They saw the pipeline as this very visible unit of measure and an aesthetic object, an organizing and orienting feature in the landscape. Sutton notes that through its development, it had transformed the way that Alaska was managed and had been a modernizing force but with massive implications for the Alaskan ecosystems and the way that Alaskans had come to view their landscape.

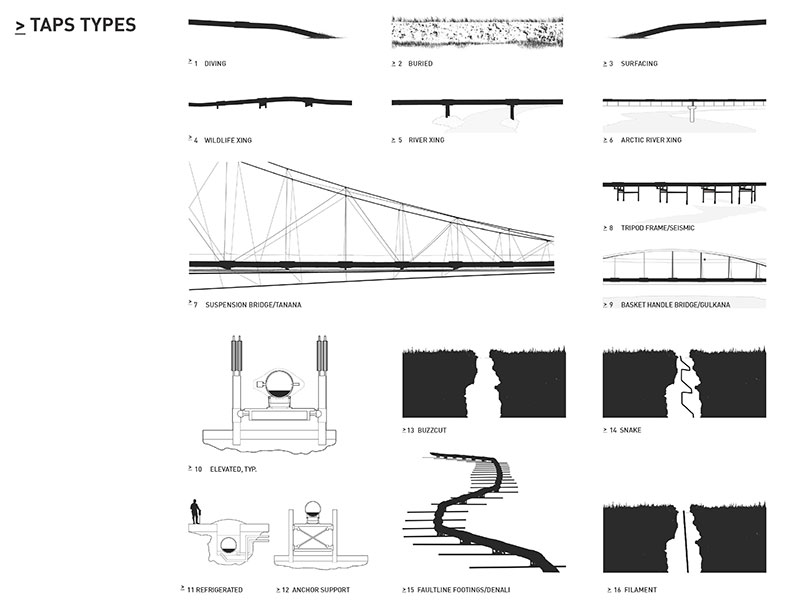

As Jenkins describes it, the pipeline has a certain elegance as it comes in and out of view, both because of the surrounding topography but also because of the way it bobs above and below the surface, sometimes buried for stretches before angling up and over the landscape. It allows the visitor to actually track changes in topography from incredible distances. It has unique structural components as it crosses fault lines, rivers, permafrost, and other geological features, thus making visible the diverse conditions at play.

Sutton and Jenkins also acknowledge that it can certainly be jarring. One doesn’t expect to see “something like this deep in the wilderness or hundreds of miles north of the Arctic Circle where there are no other signs of civilization.” Sutton adds, the experience on the trail along the pipeline “will either repel you or draw you.” Its presence is part of the modern Alaskan landscape.

Out of their research and that chance meeting with Representative Kneiss-Tomkins came the seed of an idea: a public access trail that traverses the landscape alongside the pipeline, providing access to some of the most remote and beautiful places in the world, with a combination of simple trail amenities and educational interpretation.

It is, indeed, incredible to think of the magnitude of the experience walking the 800 miles from Valdez to Prudhoe Bay. You traverse the Brooks Range north of the Arctic Circle, the Alaska Range, and the Chugach Mountains just north of Valdez. The trail crosses 834 rivers and streams including the Copper River, the Yukon River, the Sag River, and the Kuparuk. It passes through beautiful and rare ecosystems including wet sedge and alpine tundra, shrub sedge tussock tundra, black spruce forest, black spruce bogs, hemlock-spruce forests, oxbow lakes, conifer birch forests, boreal forests, glacial moraines, and morainal lakes.

Depending on the season, you’re likely to see evidence of some of the most diverse and spectacular wildlife in the Alaskan landscape including large herds of caribou on their annual migration, muskoxen, muskrat, river otter, wolverines, least weasels, gray wolves, brown bears, peregrine falcon, moose, dall sheep, hoary marmots, pikas, ptarmigan, lynx, snowshoe hares, marten, red fox, common loons, horned and red-neck grebes, trumpeter swans, belted kingfishers, alder flycatchers, and all manner of other native birds.

A handful of brave and hearty souls have hiked the entire length of the trail, after first gaining special permission. One of these is author Ned Rozell, who recounted his own experience of the adventure in Walking My Dog Jane, from Valdez to Prudhoe Bay along the Trans Alaska Pipeline. But formalizing access to the trail requires much work and coordination amongst a large and diverse set of entities with many different concerns and priorities.

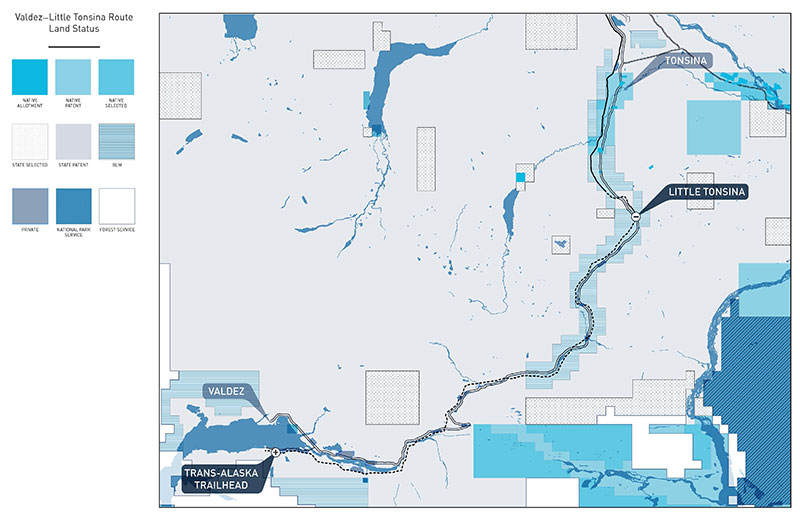

The magnitude of coordination, improvements, and new facilities needed to realize this ambitious vision is hard to fathom. Besides coordination with Alyeska for access to their easement, there is the cooperation of all landowners including 30 miles of privately held land, 51 miles of Native land, 344 miles of State land, and 375 miles of BLM land. But the concept has gotten some traction. The team led by Representative Kneiss-Tomkins has been working diligently to develop partnerships with DNR, BLM, local communities and businesses, and the Department of Homeland Security. They have also been conducting the requisite legal analyses to determine the trail’s compatibility with recreation goals. They have begun dialogue with Alyeska. Kneiss-Tomkins has established the Sitka Winter Fellowship as an opportunity for recent college grads to travel to Alaska to work on this and other projects around the state.

In 2016, the Trans-Alaska Trail was deemed feasible and viable–a huge milestone after 17 months of intensive field studies, due diligence, community engagement, and research. This year the team began investigating a 66-mile pilot segment from Valdez to the Little Tonsina River area. The pilot was chosen for its relative accessibility, its simplicity in land ownership, and because within this segment the pipeline is buried, thus mitigating some of the concerns about safety and security.

For Jenkins and Sutton, graduate work has morphed into an extended effort to support the trail through concept development and communication. So far, they have mapped and analyzed the pilot segment of the trail, identifying locations for trail improvements (new river crossings) and new facilities. The Kneiss-Tomkins team has met with local stakeholders and is working with Valdez-based Austin Love and his company Levitation 49 on adventure tourism advocacy.

As Sutton notes, “while the project is gaining traction, it is still nascent.” But they are hoping to have a wide variety of stakeholders active in the process. As winter changes to spring this coming year, two team members are headed up to Valdez and Glen Allen to further involve community members in the design of the pilot segment.

For more information you can visit the trail’s official website.