Nonprofit Spotlight: The Wildlife Federation

By Amy Nelson

Every autumn, neighborhoods throughout much of the northern hemisphere are filled with the sounds of migrating birds, shifting winds, and rustling leaves. Many managed landscapes within those neighborhoods, however, are dominated by another sound: the raking, blowing, and stuffing of those rustling leaves into “yard waste” bags to be hauled away.

Many people regard the removal of leaves and other organic debris from yards, parks, and other urban and suburban landscapes as an annual maintenance ritual, but they likely do not realize that this practice has grave ecological consequences. It removes organic matter that could otherwise be fueling the food web, protecting soil, recycling nutrients to nourish and sustain local ecosystems, and providing habitat to millions of organisms. It even contributes to climate change. The U.S. EPA reported that in 2018, American landfills received about 10.5 million tons of yard waste—7.2% of all municipal solid waste landfilled. Buried in a landfill, that organic matter breaks down in anaerobic conditions and produces methane, a potent greenhouse gas. According to 2022 data from the U.S. EPA, landfills are the third largest source of human-related methane emissions in the U.S. The removal of leaf litter also impacts carbon storage. Research published in the journal Plants, People, Planet, (Ferlauto, Schmitt, & Burghardt, 2024) suggests that long-term suburban litter raking creates legacy effects that alter decomposition and carbon storage process trajectories that are not easily reversed.

In other words, despite its unfortunate moniker, leaf litter is anything but “litter” … until people throw it away.

Unlike other challenges threatening leaf litter, such as invasive earthworms, acidification, and climate change, the removal and disposal of fallen leaves by humans seems like something that can be addressed through public awareness, education, and behavior change. Fortunately, there are organizations working on just that.

One American nonprofit, the National Wildlife Federation (NWF), has gone so far as to declare October national “Leave the Leaves Month” and implement an annual Leave the Leaves initiative that includes a public survey and robust outreach and education campaign. An organization that has been working to protect wildlife since it was founded in the 1930s, the National Wildlife Federation was deeply aware of the ecological importance of the leaf layer. In fact, the concept of keeping fallen leaves in residential yards has long been a component of the National Wildlife Federation’s “Garden for Wildlife” program.

Launched in 1973, the program encourages people and communities to establish gardens that provide essential resources for local wildlife. Initially known as “Backyard Wildlife Habitat,” it was renamed Garden for Wildlife to be more inclusive of people who do not have a yard, but may have access to rooftop and community gardens, planters, or even window boxes. “It’s the idea that we can all shepherd our own little piece of the earth by doing things like planting more native plants, minimizing or eliminating pesticides, reducing the size of our lawns, and leaving leaves,” said wildlife expert David Mizejewski. “Everybody anywhere can be involved in this kind of very local habitat restoration.”

He would know. Now in his 25th year as a naturalist and media personality for the National Wildlife Federation, he understands the power of good science communication and public engagement. Mizejewski has been advocating for the retention of leaf litter in managed landscapes for more than two decades.

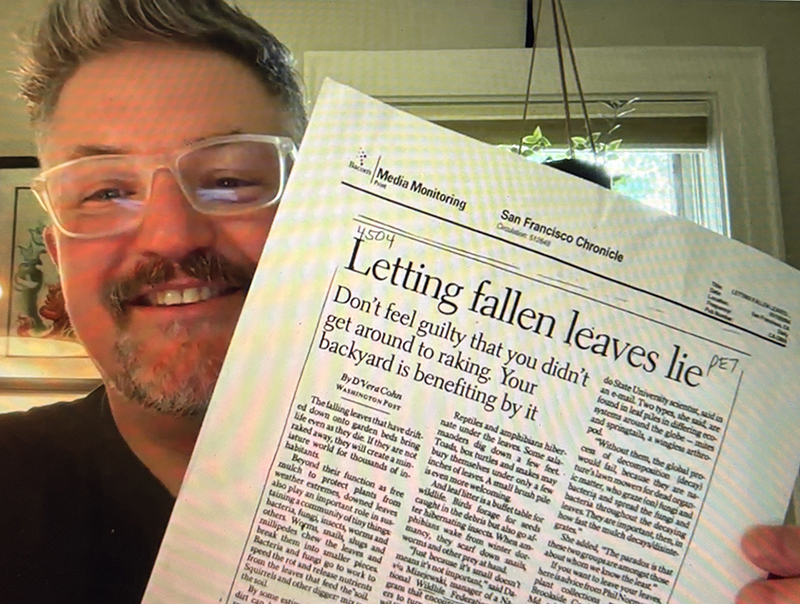

After blogging about the need to keep fallen leaves in urban and suburban yards in a 2014 post, Mizejewski noticed an uptick in engagement, including several inquiries and interview requests from major media outlets. That was his first sign that public perception of fallen leaves might be changing. The organization continued to emphasize the importance of the leaf layer in the Garden for Wildlife program, and in 2023, launched the Leave the Leaves initiative.

A primary component of the campaign, now in its third year, is the declaration of October as “Leave the Leaves” month. “October is a key month when leaves are really starting to fall in many parts of the country, and people are raking and blowing them to the curb to be thrown away or worse, putting them in plastic bags.” said Mizejewski. “That’s really what we’re trying to combat.”

Throughout October, NWF will use a variety of tools to promote messages and content that informs people about the critters and ecosystems that rely upon fallen leaves and inspires them to protect leaves in their yards and public spaces to protect wildlife, ecosystems, and the planet.

“We’re trying to be savvy about where people are consuming content,” said Mizejewski. In addition to traditional media outreach, including interviews in mainstream publications and appearances by Mizejewski on popular podcasts and television programs, where he will highlight many creatures that rely on fallen leaves for habitat, the campaign includes loads of engaging, interactive social media content. In the lineup on The National Wildlife Federation’s Instagram account, for example, are reels featuring fun and fascinating facts about some of the wildlife species that live, hunt, reproduce, and overwinter in the leaf layer. There will also be online “guess the species” quizzes, puzzles that challenge you to find critters camouflaged in fallen leaves.

Some of the creatures that might be seen in this content? Keep an eye out for box turtles, which receive critical warmth and protection from the leaf layer while they brumate during the winter. Toads and salamanders rely on the warmth, moisture, and prey provided by fallen leaves, particularly during the winter. Many overwintering moths and butterflies also depend on the leaf layer.

A study published earlier this year in Science of The Total Environment (Ferlauto & Burghardt, 2025) found that removing leaves reduced the diversity of moths and butterflies by about 40%, changing community composition by decreasing the number of species that feed internally in leaves as larvae, overwinter as larvae, or overwinter in the leaf layer. While moths may not universally tug at human heartstrings, they are an integral part of the leaf litter food web, and their absence impacts many species that are beloved by people.

“With Leave the Leaves, we’re also doing a little moth PR,” said Mizejewski. Referencing the research of notable entomologist and conservationist, Doug Tallamy, Mizejewski says that 96% of upland terrestrial birds rely on insects as the primary food source for their hatchlings and nestlings, and of the invertebrates that those birds are feeding their babies, caterpillars are number one.

When it comes to a critter that may have the greatest potential to change hearts and minds about leaving leaves, Mizejewski names the firefly. “Everybody loves fireflies,” he said. They evoke a sense of childhood wonder. But a lot of people don’t know that fireflies spend their larval phase in that fallen leaf litter.” Fireflies, which live only 30 days as adults, spend one to two years as larvae, and the larvae depend on the moist, protective, food-filled habitat provided by the leaf layer.

To gain insight into the behavior the initiative aims to change and add more compelling information to their news media outreach, NWF also conducts an annual “Leave the Leaves” public survey. The 2025 survey revealed some hopeful news. More people are leaving their leaves where they fall, with 18% of respondents reporting they don’t collect or remove fallen leaves, an increase from 15% in 2024. While this indicates a positive trend in sustainable landscaping, a third of respondents are still throwing away six or more trash bags of leaves per season. 12% of those surveyed dispose of more than 10 bags of leaves per year in the trash.

The 2025 Leave the Leaves survey found that 90% of people are willing to leave or repurpose leaves to benefit wildlife and the environment, but 40% indicated they are prevented from doing so by homeowner’s association bylaws and/or local ordinances. But policies can be changed.

“You have agency,” said Mizejewski. “Use your voice. You can be an advocate for songbird babies, salamanders, and climate resilience on a hyper local level. Get involved. Go to the town meeting. Get yourself on the HOA board.”

NWF provides resources to support such efforts, and people interested in taking action to advance local policies can reach out for help.

24% of 2025 Leave the Leaves survey participants worry that fallen leaves will smother or ruin their lawn. While ecologists and nature lovers may celebrate the ruination of turf lawns, the general public is not there yet. Mizejewski shared that many homeowners may misinterpret the “Leave the Leaves” message as an all or nothing proposition, but that is not at all the case.

“When it comes to leaving your leaves, you have options,” he said. “We know that not everyone can keep all of their leaves, and that’s OK. Keeping as many leaves on your site as you can is good, and the best way to do that is to utilize them as nature intended: as a natural mulch and fertilizer. You can save a buck at the same time!”

If using fallen leaves for mulch, Mizejewski recommends a layer between 2-5 inches deep.

In addition to using your leaves and voice, there is other action you can take today as part of the Leave the Leaves initiative. Sign a pledge to leave the leaves. You’ll not only do your part to restore local ecology; you’ll also receive the National Wildlife Federation’s email newsletter and wildlife gardening updates. If you are leaving your leaves as part of your effort to create a wildlife-friendly space in your home or community, show it off! Have it officially certified as a Wildlife Habitat by NWF.

The National Wildlife Federation is certainly not the only entity that is actively promoting the concept of leaving leaves where they fall. Some, like Wild Birds Unlimited and Xerces Society, partner with the NWF to spread the word. Others, like Woodland Trust, Peoples Trust for Endangered Species, Audubon, local watershed associations, arboreta, and even government agencies are advocating in their own ways, through blog posts, newsletter articles, videos, and more.

“Leaving the leaves is really an incredible way to live up to that old school phrase, ‘think globally, act locally,’” said Mizejewski. “Are you going to solve climate change by not putting throwing your leaves away? No, you’re not. But if I do it, and you do it, and the neighborhood does it, the benefit grows exponentially.”

Learn more about the National Wildlife Federation’s Leave the Leaves initiative. Get involved. Take action this October and every autumn, and rake in the many benefits of leaving the leaves!