Meet Your Neighbors: Life in Leaf Litter

By Amy Nelson

Illustrations by Patricia J. Wynne ©American Museum of Natural History

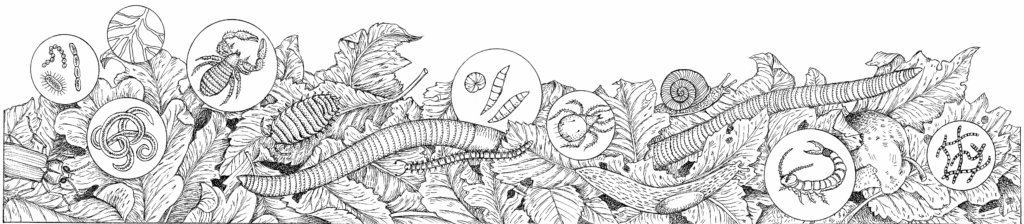

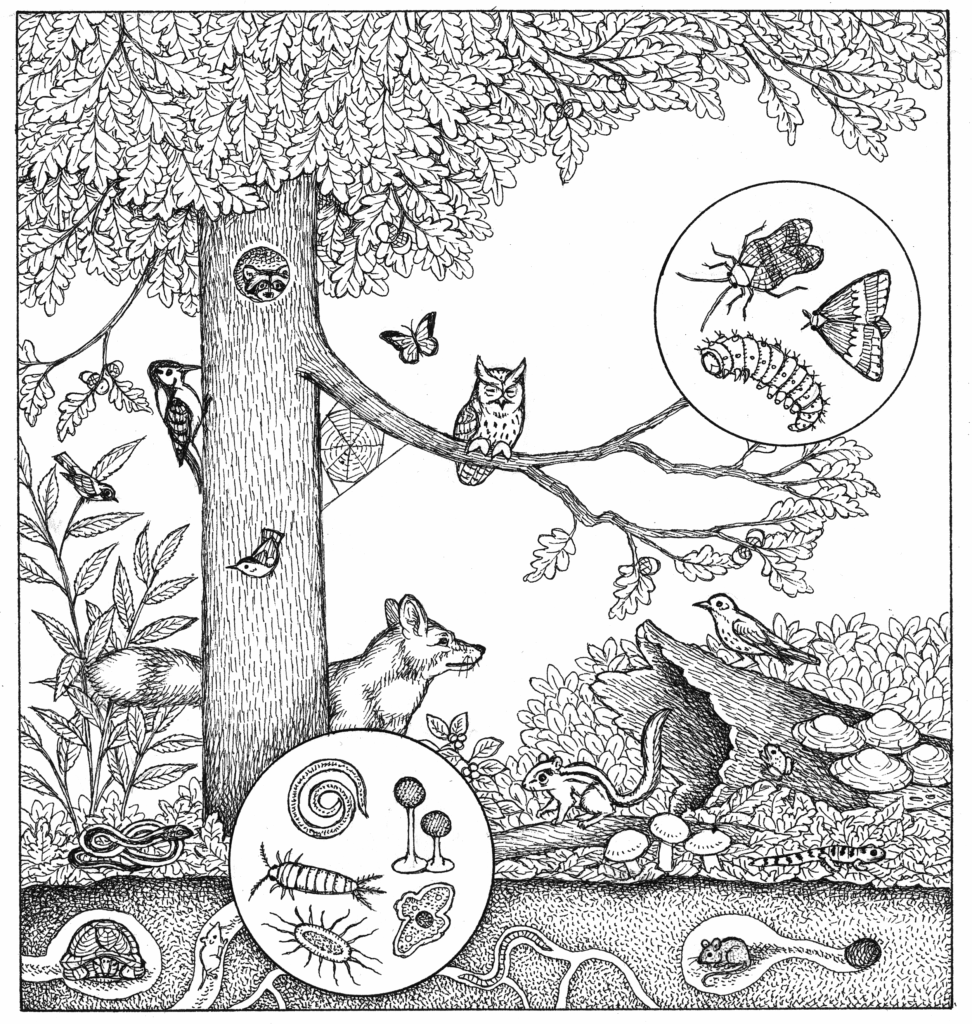

The next time you find yourself in a forest, meadow, marsh, or even a city park, pause for a moment and look down. Regardless of the season, you will likely see detritus beneath your feet. That carpet of decomposing leaves, twigs, and branches may appear to be dead, but it is anything but. It is leaf litter, and hidden within its layers is a mini ecosystem teeming with life.

Ranging from microbes to macrofauna, the community of organisms found in leaf litter is vast, varied, and veritably mind blowing. Some members of this community live their entire lives in the litter, while others may only spend a portion of their lifecycle here, or visit to forage, hunt, nest, or hide. Together, they form a complex food web that recycles essential nutrients and supports forest health and biodiversity.

When you stop and observe leaf litter, you will likely see worms and arthropods. Perhaps you’ll see a spider. Stay a few more moments and you may notice a bird or small mammal skittering about, in search of food. You might even spy a reptile or amphibian taking shelter, or a mollusk slowly consuming a leaf. And that’s just what you can see. Thriving in the layers of detritus are also the microscopic members of this community: protozoans, algae, viruses, bacteria, and fungi. The leaf litter beneath your feet is like a miniature borough whose denizens are quietly engaged in a bustling business of production, consumption, and recycling.

“Basically, you’ve got a system that is producing about five tons of stuff—branches, leaves, insect frass—per hectare each year, and the output is nutrients for plants,” said Dr. Kefyn Catley, Professor Emeritus of Biology at Western Carolina University, and former research scientist at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). “You’ve got an input and an output, and what’s in the middle is fascinating.”

The holder of a PhD in arthropod systematics and co-author of Life In the Leaf Litter, a publication produced by the AMNH’s Center for Biodiversity and Conservation, Catley knows a thing or two about what is happening within leaf litter.

“I used to tell my students that there is not a single biological phenomenon or set of relationships that you can’t find in a leaf litter,” he said. “From predator and prey to commensalism, mutualism, and symbiosis. It goes on and on.”

While the bulk of production occurring in leaf litter is done by the plants themselves through photosynthesis, some algae and bacteria are also converting sunlight into food. And boy, is there food. For thousands upon thousands of creatures, leaf litter is like a 24-hour smorgasbord. Among its diners are herbivores, predators, scavengers, parasites, hyperparasites, and parasitoids. There are even coprophages, organisms that eat the feces of other organisms.

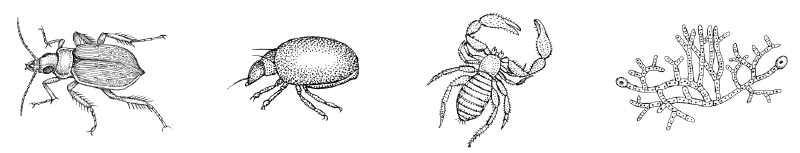

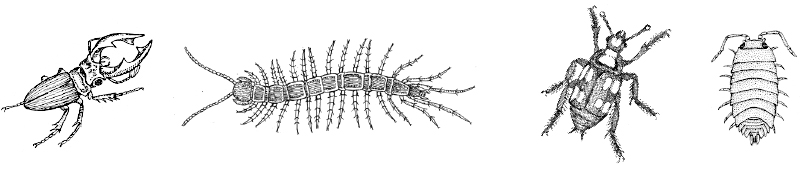

The most abundant group of invertebrates in leaf litter are springtails (Collembola) and mites (Acari). A single square meter of forest leaf litter and soil can contain up to 50,000 individual springtails and 250,000 individual mites. Springtails are found throughout all layers of the litter, converting the leaves, algae, fungi, nematodes, and other items they eat into humus. Mites feed on litter, algae, fungi, and sometimes smaller invertebrates. Springtails and mites may be eaten by predatory mite species, and they are both a food source for spiders and centipedes, which are then preyed upon by a variety of animals, including birds, ground beetles, toads, frogs, shrews, and mice.

Despite their abundance and important roles in the food web, mites and springtails are not the primary decomposers of leaf litter. That title is held by fungi and bacteria. Releasing enzymes that break down organic matter and into soluble nutrients they can absorb, bacteria and fungi are responsible for 80-90% of the decomposition of dead plant and animal matter in leaf litter. Both are critical to the chemical breakdown and cycling of nutrients. Fungi is the only organism that can break down lignin, and bacteria is highly effective at breaking down simpler compounds. Bacteria and fungi are also food sources for many organisms in the leaf litter.

The work of fungi and bacteria is made easier by invertebrates like slugs and snails (Mollusca), roundworms (Nematoda), worms (Annelida), and millipedes (Diplopoda), which shred the litter into smaller fragments as they consume. As these macrofauna move through the litter, eating and excreting it and in turn being eaten by predators, they, too, play important roles in nutrient cycling. In the case of earthworms, they are also creating spaces in the soil that allow for the movement of air and water. But earthworms in leaf litter are also problematic.

Glaciers killed nearly all native earthworms in North America, so those found in leaf litter are largely European (primarily Lumbricus terrestris and Lumbricus rubellus) and, more recently, Asian (particularly Amynthas agrestis, Amynthas tokioensis, and Metophire hilgendorfi). These introduced, invasive species are dramatically impacting leaf litter and fundamentally changing the structure and properties of the soil and leaves. A study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution in 2024 found that North America has been colonized by at least 70 alien earthworm species. The study also revealed that these earthworms have larger geographical ranges than native species, and that they pose “a serious threat to the biodiversity and functioning of native ecosystems.”

“There’s nothing quite as horrible to me as finding what looks like a nice piece of leaf litter in a small woodlot, and you scrape off the top layer of leaves and find that underneath it’s just worm casts,” said Catley. “There’s no interface at all between the soil and leaves. The worms are destroying it.”

Unfortunately, such sight that is becoming increasingly frequent in many North American forests as the Asian worms continue to spread rapidly. Known as “jumping worms” for their fast, thrashing movement, they grow, reproduce, and consume leaf litter much faster than European earthworms. By depleting the leaf litter, invasive earthworms are also causing declines in native plants, fungi, and animals that depend on it.

“Earthworms will actually take leaves that are relatively fresh (a year or two old) and pull them down into their burrows in the soil,” said Catley. “In doing this, they’re diluting the structure, the food source… everything.”

The spread of invasive earthworms has been caused and abetted by humans through the purchase of worms for bait, composting, and vermiculture, and through potted plants, and gardening equipment and material, Though many organizations are working to control the spread of non-native earthworms through public outreach and education, and researchers are exploring options for killing them, there is currently no known method for completely eliminating them.

There is, however, a method for eliminating some invasive earthworms: eating them. They are a good source of protein and are eaten by humans in some cultures. In leaf litter, they are gobbled up by birds, beetles (Carabidae and Pselaphidae), and smaller worms are preyed upon by centipedes. Efficient hunters, centipedes also prey upon many other invertebrates in leaf litteWhen it comes to dominant predators in leaf litter, however, spiders take the honors. Predatory spiders in the leaf litter include sheet weavers (Erigoninae) and funnel weavers (Agelenidae), as well as free-hunters, like jumping spiders (Salticidae) and wolf spiders (Lycosidae). Other arachnids preying on smaller invertebrates in the leaf litter include pseudoscorpions and Harvestmen (also known as “daddy longlegs”).

Some leaf litter invertebrates, like sowbugs and pillbugs (Crustacea), double-tails (Diplura), proturans (Protura), book lice (Psocptera), and earwigs (Demaptera) are scavengers, eating dead and decaying vegetation, algae, lichen, and fungal mycelia and spores. These arthropods are then eaten by a variety of predators, including mites, spiders, beetles, pseudoscorpians (Pseudoscorpiones), and some snakes and birds.

Birds, along with many other animals, are also drawn to leaf litter by another source of food hidden within it: the larvae, pupae, eggs, and bodies of creatures like butterflies, moths, bees, mice, shrews, and voles that may overwinter in the leaf litter.

“We have a lot of turkeys where I live, and they are constantly scraping the leaf litter,” said Catley. “They know exactly what’s down there and how to find it throughout the spring and winter time.”

Given the importance of birds in pollination and seed spreading, it is easy to make the connection between a thriving leaf litter community and the biodiversity of the larger ecosystem of which it is a foundational part.

How do the communities of critters in leaf litter differ by forest or ecosystem type? “The basic difference is pH,” says Catley. “You might assume that leaf litter biota in a white pine plantation would have very low biomass, and that is not necessarily the case.” Catley explains that a multitude of mite species are adapted to the lower pH of conifer forests, and pine needles can take 40 years to decompose and be recycled back into the ecosystem (compared to five years for an oak leaf). “If you take samples from a deciduous forest and a coniferous forest, you find equal abundance, but less richness in the conifer forest.”

Litter in a mangrove forest, for example, may be home to amphipods, which eat decaying plant material or microalgae, and in turn are eaten by sesarmid crabs (Sesarmidae), which also process leaf litter. A crab may then be eaten by a wading bird, raccoon, shark, or sea turtle.

Microbes that are decomposing prairie leaf litter are eaten by invertebrates adapted to that environment. Those invertebrates may in turn be eaten by a grasshopper (Caelifera) that is then preyed upon by a shrew, fox, or snake.

How can you learn more about leaf litter, discover what is eating, hunting, nesting, and taking cover in the leaf litter beneath your feet, or better yet—inspire others to do so?

Dr. Catley recommends grabbing a sample, bringing it into the lab and using a Berlese funnel to see what is living inside it. A Berlese funnel is essentially a tractor funnel with a light and heat source at the top, a screen in the middle, and a container of preservation liquid at the bottom.

“You put the leaf litter sample on top of the screen, and the light and heat—two things that arthropods and other organisms that live in the leaf litter hate—drive the organisms down through the leaf litter and into a beaker of alcohol,” said Catley. “You may have to leave the litter in the funnel for several days, depending on the amount of moisture in there. But once you get that alcohol in a Petri dish and look at it through a microscope, it’s just mind blowing.”

Catley shares that his University students often thought they’d been tricked when they saw what was in the petri dish. “They took the sample,” he said, “and when they looked at it in their hands, there’s nothing in there except, perhaps, the odd spider.”

“That [experiment] is a point of entry I think everyone should have as part of their general education because it enables them to understand the diversity of, and ecological connections between, different groups organisms,” he said. But there is still much to learn about life in leaf litter, including how it may be impacted by climate change.

“As with any biological systems, the parameters (moisture, temperature, and pH ranges) are very much fixed,” he said. “I can see a situation where, sometime in the future these systems could start breaking down because the mites can’t operate if the leaf litter is too wet or dry, or if the pH is fluctuating all the time. That’s going to reduce the amount of biomass the system is producing, and that biomass is feeding birds, mammals, and the other vertebrates. And if the nutrients are not being recycled to the plants… well, it is a pretty scary thought.”

“Leaf litter is such a complex system that we still know so little about,” said Catley. To illustrate that point, he shared an anecdote from his time studying leaf litter in Central Park while working for the American Museum of Natural History.

“We took samples from six or seven different places around Central Park to examine how the litter was different in wetter areas vs. dryer areas. We ended up finding three new species of fungus gnats living in that leaf litter. We also discovered a new centipede—not just a new species, a new genus. This thing had been living in Central Park—the ultimate urban area with three million visitors walking over it every day. It was the smallest centipede in that group that has ever been found, and it was in Central Park. That’s gives us some idea of the extent of our knowledge about life in leaf litter.”

This year as the leaves start to fall and litter the ground, think about all of the organisms in those layers, which are not only living but supporting the entire ecosystem around you. Perhaps you’ll look at your own yard differently, and choose to leave those leaves where they fall. If your neighbors complain, show them this article, and maybe they too, will decide to leave their rake in the shed for another year. After all, it really is the neighborly thing to do.