Expert Q&A: Dr. Joe Roman

By Amy Nelson

Joe Roman, “editor ‘n’ chef” of eattheinvaders.org, is a conservation biologist, marine ecologist, author, and fellow at the Gund Institute for Environment at the University of Vermont. His research, which focuses on endangered species conservation and marine ecology, has been covered by media outlets such as the Associated Press, National Public Radio, The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post. Joe is the author of Eat, Poop, Die: How Animals Make Our World; Whale; and Listed: Dispatches from America’s Endangered Species Act, winner of the Rachel Carson Environment Book Award. His science and nature writing has appeared in The New York Times, New Scientist, Audubon, Conservation. Joe has been a Fulbright Scholar in Brazil, a McCurdy Scholar at the Duke University Marine Lab, and a Hrdy Visiting Fellow at Harvard University. He has also worked at the University of Iceland, the University of Havana, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. We were thrilled to have a chance to chat with him about his passion for eating invasive species.

How did you become interested in invasive species?

I’ve been interested in conservation biology since the 1990s. In conserving wild species, the biggest issues are probably overhunting and overfishing, but those tend to be the easiest to turn around. For example, many whale populations are much better off now than they were in the 1970s because of the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Other big issues impacting biodiversity are, of course, habitat destruction and climate change, but you cannot ignore the role of invasive species in biodiversity conservation. I grew up on Long Island in New York, and I’ve worked on several islands. On island systems, you really see the impacts of invasive species. So even if invasive species weren’t the first thing I considered when thinking of ways to restore native wildlife, they were always a top concern. I became more directly interested in invasive species while doing my PhD. I was studying the movement of the European green crab (Carcinus maenas), one of the most invasive marine species. It comes from Europe and North Africa, and it is now found on every continent except Antarctica. In many ways, it is the perfect invader: it has high fecundity, it is very aggressive, and it can live in cold, warm, salty, and fresh water.

We’ll talk more about that crab, but first… how would you describe the impact of invasives on biodiversity?

Let’s pick three ways they influence biodiversity. Invasive species can be predators, like rats or green crabs. These species come into an area free of the controls of the ecosystems where they evolved, so they can feed and overgraze on other species. Plants can also be very invasive, often because they are outcompeting other species. In just the 20 years that I’ve been in Vermont, for example, I’ve seen Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) come in and really form dense monocultures along river systems in areas that are highly disturbed and have some light.

Another issue with invasives is that they often carry diseases or they are disease agents. One of many devastating examples is the unintentional introduction of mosquitoes to Hawaii, resulting in the extinction of dozens of unique bird species that are never coming back. The larvae probably came in the water of whaling ships. Often island species are the most vulnerable. They tend to have small habitats and have unique, evolutionary modifications that allow them to thrive there. But once a new disease agent comes in, they can be devastated.

Your most recent book, Eat, Poop and Die, is all about the movement and cycling of nutrients across the planet. Do invasive species impact this?

This is a new aspect of zoogeochemistry. There aren’t a lot of studies looking at the impact of invasives on the movement of nutrients, but in the Chagos Islands, [researchers led by marine biologist Nick Graham of Lancaster University] found a connection between invasive rats and coral reef ecosystems. They studied islands with and without invasive rats. They found that seabirds [which are preyed upon by rats] come into the islands without rats and release guano across the coral reefs in those areas. Nutrients in the guano are enhancing growth that allows the coral systems and more fish to thrive. That’s a cool study showing how invasives can have very clear effects [on the movement of nutrients and the ecology of a system].

What do we really know about the economic impact of invasive species? I’ve seen all kinds of estimates, and many opinions that those amounts are grossly underestimated.

There are estimates of hundreds of billions of dollars a year in impacts. The late Professor David Pimentel of Cornell put out one of the first papers quantifying the impacts in the United States. [Pimentel projected that invasive species cost the U.S. economy more than $138 billion annually.] The IUCN also has good information on the economic impact of invasive species.

We can see crop losses from the introduction of invasive species. Just look at tree mortality. I’m seeing ash trees disappear here in Vermont and Quebec in a very short time. There are also impacts to human health. Look at the impacts of invasive mosquitoes. I mentioned their impact on birds in Hawaii, but invasive mosquitoes also spread West Nile virus, Dengue fever, and other diseases to humans. We’ve spread invasive diseases around the globe, which have a clear economic and health impact.

There are also indirect impacts, like the decline of pollinators. And finally, invasives can change the shape of ecosystems. Invasive crabs impact dunes and reefs, for example. That is a loss for the diversity and ecology of the system, but it also puts humans at greater risk from storms or climate change. I’m giving you a sample. There are probably hundreds of impacts every day, and the thing about invasives is once they’re in, they’re hard to remove, so the impacts are long-lasting.

There’s also the cost of trying to manage them and control invasive species.

Exactly. Insecticides, herbicides, direct removal. I don’t have the numbers offhand, but if we think about the application of pesticides and herbicides to reduce the impacts of invasives, it’s substantial in terms of time and money.

How did you first arrive at the idea of eating invasive species, and what early obstacles did you face?

In 1999 I was working in the field in Nova Scotia, looking at the pattern of invasion for European green crabs. I would stop every 50 kilometers or so along the coast, from Cape Cod to Cape Breton and look for these crabs at low tide. One day I noticed that someone else was also crawling around the rocks, but he had a bucket. His bucket was full of European periwinkles (invasive snails), which he was selling to markets in Boston, New York, and Montreal, where European or Chinese cultures use snails in their cuisine. I don’t know if he knew that they were invasive. That wasn’t the point. But he was collecting an invasive species out there while I was doing my genetic study.

So I started collecting the crabs and periwinkles, too. One afternoon I found some soft shell green crabs, and I went back to where I was staying and cooked them up. Then I tried cooking periwinkles and they were delicious! You just pick them up out of the ocean and bring them right into your kitchen. They’re so easy to prepare. You just boil them with some garlic and butter or olive oil and eat them with some good bread.

At that point I consulted the book Stalking the Blue-Eyed Scallop, by Euell Gibbons, a 20th century forager who wrote about collecting, and cooking wild food. The book helped me learn how to harvest and prepare these foods and it also provided a recipe or two. Gibbons didn’t care about invasives. He was just thinking about how to forage. So I started collecting some invasive species that are easy to prepare—like dandelions, garlic mustard, and Japanese knotweed. These plants taste so good in the spring, but after that they get pretty woody. Invasives are almost all seasonal in some way, so it’s not something you can just go out anytime and collect.

I collected a bunch of recipes over the years, and in 2001, I proposed an article about eating invasives to Audubon magazine. The response was pretty much silence. There was a little bit of a “this is kind of a funny idea” reaction to the concept of eating invasive species, but there were also scientists who strongly opposed it. But something changed in the following years, and the article finally came out in 2004. There was some response, but it was somewhat muted. The term “locavore” wasn’t even around then, but people soon started focusing on where their food came from. I think this is cyclical. When Euell Gibbons was writing in the 60s and 70s, foraging was culturally popular, but in the late 90s, it wasn’t. Once that started to change, I started getting calls from journalists and scientists. That is also when I started working with chefs.

I’m a biologist, so why would you trust me when I say that a green crab tastes good? But if you went to your local restaurant and they prepared it for you and it was tasty, you might start thinking, “I want to try this at home.” A few species have helped move that forward and I think one of the best gateway species is lionfish. It is a firm white meat, so it is pretty easy for most people to try. If you like fish, you’re probably going to like lionfish. I think lionfish started to be a game changer, where people began to think, “Maybe eating invasive species is actually a thing.”

Let’s be clear, eating invasives is not going to eradicate a species. But I am excited by the idea of “functional eradication”—if you reduce the population enough, it can have an impact on native biodiversity. A couple of research papers [one published in Reviews in Fisheries Science and one published in Ecological Applications] have looked at the impact of lionfish fishing/hunting on the restoration of native fish populations. Perhaps unsurprisingly, in heavily fished areas, lionfish populations go down. In areas that aren’t heavily fished, populations either expand or stay the same.

But functional eradication doesn’t work if we just keep having new invasives coming in all the time. The best thing we can do is prevent new invasives. As with disease ecology, we want prevention and early treatment. Eating invasives comes down the road, when we acknowledge that they’re already here and widespread.

How did you start working with chefs?

I was driving through New Haven, Connecticut, with my family, and I had heard about this chef, Bun Lai, who had started serving invasive species at his mom’s sushi restaurant there. [Bun is still there and he does events, but he is no longer operating the restaurant]. We stopped at the restaurant and Bun served these tiny Asian shore crabs, which have displaced European green crabs in some places. One writer described the way Bun prepared them as “Doritos with legs” and I think that’s true. They are crunchy, well-spiced, little crabs. Bun also had an invasive species menu and when I saw it, I thought, “This is amazing!” But he didn’t actually serve most of it; it was imaginary sushi.

Bun was one of the early adopters of this idea, but since then, I’ve found a lot of chefs who are open to serving things like green crabs because they want to serve fresh, local cuisine. There is now an entire organization dedicated to promoting the consumption of green crabs on the East Coast [greencrab.org]. CJ Chavers even wrote an article about eating European green crabs in the New York Times last January (Bun and I are in the article). Fishers of Chesapeake blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) know when they’re about to molt, so they can collect the hard shell crabs and hold them until they molt. There are efforts to figure out a way to reliably harvest European green crabs as soft shells. Once that happens, you’re going to really see an increased desire because they’re delicious.

Eating invasive is still very niche. You’re probably not going to see an invasive species in your grocery store, and if you do, it probably won’t be promoted as invasive. It’s still going to be a few creative and/or environmentally minded chefs that are putting it on their menus. Bun was the first, but I have since worked with many other chefs.

I had a wonderful experience at the Chefs Collaborative in Boulder, where, a chef served grocery store natural pork, a heritage pig that he raised, and a wild caught, invasive feral hog—side by side. The difference was amazing. The wild hog meat was darker, and the flavor was much more complex. For many people, when they order or cook pork, they want to know exactly what they’re getting. With the wild species, though, there’s more variation. It’s so much more flavorful and interesting. The challenge with something like feral pork is that of course it has to be inspected if you’re selling it commercially. Unfortunately, very few producers are going to be able to hunt it, get it inspected, and get it on the market.

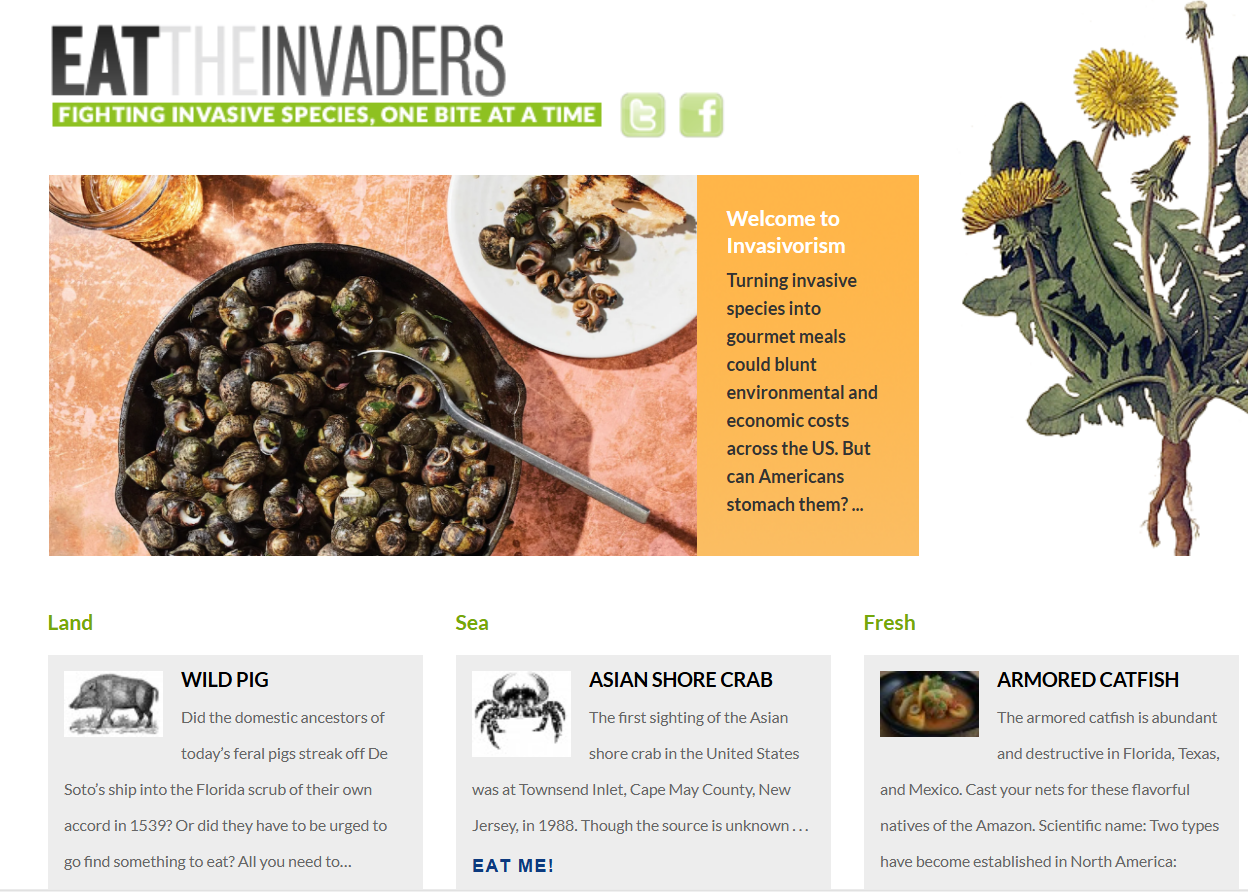

How did you happen to start the website eattheinvaders.org?

A few years after writing that article for Audubon, as well as others for New Scientist and Conservation in Practice, I thought, “There should be a place where we can put all of this information together and make it publicly available. The website came out in 2011. It has brought some increased attention to this idea. It was fun to look for recipes and think about what species would be eligible for the site. An important note is that I don’t talk about eating rats or things that are gross. There’s no fear factor in my website. It’s all species that are tasty, healthy, and consumed pretty regularly.

I didn’t see any insects on the website.

I cannot think of an invasive insect that I would actually want to eat. Conservation is often about making up for our sins and errors. There’s a lot of guilt, and I carry it, too. But this website is not about that. It’s about eating these species to learn something, have a good meal, and possibly have an ecological impact. The goal of eattheinvaders.org is really about education and understanding the environment and environmental history of the systems around you.

You mentioned that early on, some scientists were opposed to the idea of eating invasive species. What are some of the concerns of critics?

One is that if we create a market for these species people will want to have them around. The worst thing that could happen with this idea is that people would want invasive species in places where they’re not yet found and spread them. This is not the goal of this effort. Eating invasive species is more about education, getting a good meal, and how reducing species can go hand in hand with efforts to eradicate them. We’re still in the very early days. Dan Simberloff, an invasive species biologist at the University of Tennessee is not a fan of eating invasive species. He published a paper about his concerns, which included those I mentioned as well as whether the species becomes part of the culture. Then people want to maintain it, even if it’s not commercially important it might become important culturally.

Let’s talk about that educational aspect. As you say, we can’t eat our way out of this problem that we created. But one thing all humans have in common is that we all have to eat. Could eating invasive species be a new angle to move the needle and bring more people into the conversation?

I think lionfish has done that in the United States. It has gotten a lot of attention and people are aware of the species coming in. The message has gotten out through lionfish derbies and seeing lionfish in restaurants. Seeing something in restaurants makes a difference. Sushi is a classic example. Americans didn’t really eat raw fish more than 50 years ago, but now you can find it in a small strip mall anywhere in the United States.

Where do you think the impact of eating invasive species will be greater: in generating public awareness or reducing numbers of invasive species and giving native species a better chance at recovering?

It depends. In some places, it’s actually going to be about the impact, like fishing lionfish and seeing the changes. Eating Japanese knotweed here in Vermont, however, is not going to result in a decline in Japanese knotweed or have much of an ecological impact, but you’re going to learn something and you might have a good meal while you’re at it. It’s very place based.

Is there an invasive species people aren’t yet eating for which you see great potential for consumption to have an ecological impact?

“I don’t know” is the short answer. I can give you a list of species that I think are pretty tasty, but the hard part is commercializing them and getting them into the marketplace. To date, that has been a challenge for many species. The ones that are probably going to be the easiest are fin fish because there’s a demand for that. It is seen as healthy, and if it’s packaged right, it’s familiar. There are no barriers to preparation. Whereas something like the European periwinkle, which are unfamiliar to many Americans and kind of hard to get out of the shell, is harder to get into the average American grocery store.

A species that is invasive and problematic in one place can be native, beneficial, beloved, and regularly on dinner plates in another. Is that where the idea to eat invasive species, as well as some of the recipes, comes from? It’s just like, where are these native and eaten and enjoyed?

One hundred percent. My great-grandmother immigrated to the U.S. from Italy, and she would go down to the beach in New York and collect mussels, clams, and snails and serve them with a good red sauce. I have actually prepared periwinkles using my grandmother’s sauce recipe! She would also collect and cook dandelion greens and other plants.

When I forage I often see people from different cultures out there foraging, too. People with connections like that might maintain foraging traditions even after they’ve immigrated…even if the next generation might be fine getting most of their food from the supermarket. Another advantage of this movement is the idea that you can actually have a meal that’s not wrapped in plastic and shipped across the world.

How do you vet these invasive species to make sure that they’re safe and that they are harvested, prepared, and eaten responsibly?

Blue catfish is invasive in the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland’s response—and this is true for the invasive northern snakehead too— is to encourage people to fish and harvest them. Virginia, however, does not want people to go out and harvest them because they are concerned about the impacts of people moving them around. So it is important to know local regulations. You also want to be sure that you identify the species correctly. iNaturalist didn’t exist when I started out, but it is an amazing resource. It is also helpful to go foraging with and learn from an expert.

You need to consider health. You shouldn’t forage where herbicides or pesticides are being spread, or where there are other contaminants. If you’re going to fish for native species there, it’s likely the invasives are going to be fine. But if it’s an area that you’re worried about, you should be very careful. Burmese Python is an example invasive species. It is now found throughout a large part of southern Florida, but there are concerns about mercury contamination. I wouldn’t recommend eating it.

I also consider taste. Does it actually taste good? I usually read recipes from the native countries of invasive species to help figure this out. Eating invasive species should not be a form of penance! I also think about effectiveness. Is it likely that harvesting the species is going to have an impact? Eating dandelions is not going to impact dandelion populations, but you might get some very nice greens from it and it can have an ecological impact.

Do you have any advice for professionals in the food industry who may want to adopt this practice responsibly? What should they watch out for in terms of safety, unintended consequences of harvesting, regulatory hurdles or messaging?

You need to know if there are harvesting restrictions (as there are in Virginia for blue catfish, for example). Chefs will know this, but there will also be concerns about inspection and food safety. Plant species tend to have fewer rules, so you see foraged plant species on the menu more often. Often, a chef will champion one particular species, and that has gotten it into a restaurant. Except for Bon, I can’t think of any restaurant that has made invasive species its theme. But there are restaurants that have lionfish, green crabs, or periwinkles on the menu, or some foraged invasive plant species in their salad. To date, I haven’t seen any restaurant saying, “Invasive species is our niche.” It would be really cool if one did, though. I’d certainly go.

What species would you recommend for a home cook or forager who is interested in this idea but has never tried an invasive species? You did say lionfish is the gateway…

It depends on where the person is and whether or not the species has gotten out on the market. If you’re in a place where you can get access to lionfish, I would definitely recommend that. In and along river systems, there are plenty of invasive aquatic species that are tasty. Bullfrogs are one example. Although they are native to the East Coast of the U.S., they are invasive on the West Coast, and a very large predator in aquatic systems. Out there, harvest them! You won’t eradicate them, but it could have a small impact. Bullfrogs are an example of the importance of knowing where you are.

I wouldn’t encourage the global sale of invasive bullfrogs, though, because I’m concerned that people would want more frogs’ legs, and they are already in too high demand. As with the foraging movement, you need to know your environment.

Do you have a favorite invasive species recipe? Would it be the periwinkle dish with your great grandmother’s sauce?

It is. That’s partly because it is associated with my childhood and my great grandmother, and partly because I created the dish myself!

Find this recipe and more on eattheinvaders.com.