Biohabitats Projects, Places & People

By Amy Nelson

Projects

Say “Aloha” to Sustainable Water Management on the Big Island

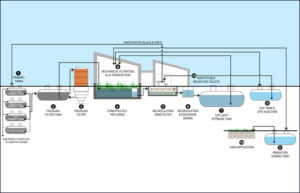

The five-acre campus of Hawai’i Community College–Pālamanui in North Kona, is being developed over a ten-year period. The College is striving to achieve sustainable design goals and achieve LEED Platinum status. Given its location in North Kona, on the arid side the Big Island of Hawai’i, it is not surprising that sustainable water management was a key concern for the campus. Collaborating with Roth Ecological Design International, and applying an integrated water strategy that combines stewardship of water resources with facility needs, water conservation, campus aesthetics, and ecological enhancement, Biohabitats designed a system to collect, treat, and reuse wastewater onsite. The 8,300 gallon-per-day system, which combines mechanical and biological processes, uses engineered wetland technologies that mimic the natural treatment processes of marshes and wetlands. These constructed systems, which include native plants, transform ‘pollution’ into food for wetland organisms. The living engine driving this technology employs the food web structure found in natural marshes: microorganisms, zooplankton, algae, and higher plants. The effluent is then used for landscape irrigation.

Sauvie Island: At the Confluence of Stewardship & Transformation

The Sauvie Island Wildlife Area, located ten miles north of Portland, OR, at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers, supports a rich assemblage of over 275 species of birds, 37 species of mammals, 12 species of amphibians and reptiles, and numerous species of fish and plants. Founded in 1947 and managed by the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife, the site also provides important rearing habitat and food web exchange for several species of out-migrating juvenile salmonids. Since the 1930s, hydrological modifications to support regional agriculture and development on Sauvie Island have interrupted important natural processes, which has led to habitat degradation. Fortunately, the Columbia River Estuary Task Force (CREST), which initiates efforts to restore habitat on the Columbia River Estuary, launched a project to remove three fish passage barriers and earthen berms, remove a dilapidated culvert, install a refurbished rail car bridge, and restore and lower the elevation of tidal marsh, and manage invasive species.

With the end goal of maximizing habitat potential for juvenile salmon and other wetland-dependent species, Biohabitats worked with CREST to implement the project in the fall of 2015. Although challenges included the site’s remote location, the presence of threatened and endangered species, and a diverse group of stakeholders that included ranchers and recreational users, we were able to complete this large complex project on time and under budget. Today, the site has a mosaic of tidal and freshwater wetland complexes that provide a rich diversity of habitat types due to CREST and Biohabitats’ efforts that increased floodplain hydrologic connectivity, tidal marsh area, and site revegetation.

A Living Library of Urban Habitat & Innovative Stormwater Management

Behind one popular branch of Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library is a 1.1-acre wedge of green space surrounded by blocks of pavement and urban development. Known as “Library Square,” the land sits directly atop Harris Creek, a buried stream that conveys a tremendous amount of stormwater toward Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, and contributes to flooding and pollution. When Blue Water Baltimore, in partnership with Banner Neighborhoods and Friends of Library Square, won a Chesapeake Bay Trust Fund Grant to create a stormwater management plan to treat stormwater runoff from 25,000 square feet of the surrounding roads and sidewalks, they turned to Biohabitats for help. Together, we crafted a design to maximize stormwater management and improve the park’s aesthetics and sustainability with innovative and attractive pervious surfaces and native plant bio-retention features that promote urban ecology and creates new habitat for pollinators. All while also responding to the community’s need for an active and safe open space. The design also maintains a canopy of mature Linden trees (Tilia americana). We’re delighted to report that construction has now begun. We’ll be sure to keep you posted on the transformation of this vibrant city park.

Award-Winning Chatham University

After teaming with BNIM, Andropogon, Civil and Engineering Consultants (CEC), and Interface Engineering to create a campus master plan for Chatham University’s new 388-acre Eden Hall campus, Biohabitats worked with Mithun, CEC, and Interface to create advanced natural wastewater treatment systems which integrate closely with the learning landscape of the new campus. The high-quality reclaimed effluent is reused to supply 100% of the project’s toilet flushing demand. Any excess unused effluent is slowly and safely dispersed back into the soils through subsurface irrigation systems. This fall, the project earned the AIA Pittsburgh’s Award of Excellence for Engineering & Design!

Poised for Floodplain Improvement in Northeast Ohio

With its ball fields, swimming pool, and tennis courts, Kerruish Park in northeast Ohio is a recreational oasis in a landscape bordered by residential development and roadways. It also holds great potential as an ecological corridor, as it includes a densely forested area containing a large, perennial stream known as Mill Creek. At some point, in an attempt to control stormwater, an earthen dam and a detention basin were created. Work to further increase the basin’s storage was completed in the early 2000s. However, sedimentation, woody debris, poor water quality and lack of fish passage through the reach have been an ongoing problem. After developing a conceptual design to restore 2,000 linear feet of the creek and its riparian area, Biohabitats collaborated with the Cuyahoga County Board of Health, Mill Creek Watershed Partnership, West Creek Preservation Committee, Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District, and City of Cleveland division of water pollution control to develop a schematic 30% design. The funding for the project was generously supplied by the Ohio EPA’s 2015 Cuyahoga Area of Concern (AOC) Habitat Restoration Project Planning Grant through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) Fund. The restoration will improve fish passage over two sewer lines which are acting as lowhead dams, provide more stormwater storage by reconnecting the stream to a floodplain, and improve water quality through increasing stormwater and sediment storage on the floodplain, groundwater/surface water interactions, and instream habitat diversity. The restoration also allows the wooded stream to become a safer and more engaging and accessible recreational feature in the park. With a schematic design in hand, the Mill Creek Watershed Partnership and there partners can now further explore funding opportunities to help bring the restoration closer to reality.

No Idle Time in This Urban Park Restoration

Teaneck Creek Park is one of the few remaining natural areas in the heavily urbanized landscape of northern New Jersey. A transitional habitat zone between the Meadowlands and the Highlands, it is also an important birding, educational and recreational resource. The park sits along Teaneck Creek, which ultimately drains into the Hackensack River. Over the years, portions of the park have been dramatically altered due to land use developments, debris dumping, and the site’s adjacency to the surrounding urban landscape. Like most urban parks, Teaneck Creek Park is overrun by invasive plant species that threaten biodiversity and native habitats. Thanks to the efforts of Bergen County, the Teaneck Creek Conservancy, Rutgers University, and the New Jersey Audubon Society, the park is now protected from any further development and dumping. Biohabitats is working with Bergen County on a wetland, stream and riparian restoration plan to help restore the habitat and ecological function to the park. The plan works to capture the swiftly flowing stormwater that has eroded parkland and degraded water quality so badly that one outfall had been dubbed “stormwater canyon.”

Using a regenerative stormwater conveyance (RSC) approach, the restoration will slow the water down, spread it out further across the site, and allow it to soak into the ground. The ultimate goals are to restore wetland and riparian habitat, better manage invasive plant species, improve water quality, and enhance public use of the park. While the restoration design progresses and permits are obtained to undertake construction, project team members from the Bergen County Division of Open Space, Rutgers University, and Biohabitats have been supporting Conservancy volunteers’ efforts to manage the park’s natural resources. Biohabitats has been working with the Conservancy’s all-volunteer “Weed Warriors” to remove invasive species and develop a long-term management guide to further efforts.

Improving Urban Life & Ecology in Pittsburgh

Biohabitats has been selected as part of a team led by WRT to reclaim Heth’s Run Valley, a part of Highland Park in Pittsburgh, PA. The valley encompasses the Pittsburgh Zoo and PPG Aquarium parking lots. The City of Pittsburgh, in partnership with the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy and community groups, is working to transform the valley into network of trails, recreational facilities, restored habitat and green infrastructure.

Demonstrating Tools for Change in Urban Stormwater Management

For organizations initiating community improvement projects in Baltimore, the Baltimore Community ToolBank is a godsend. The organization, which loans high quality tools and equipment at a fraction of the typical cost, has made countless volunteer construction and greening projects possible. This fall, the ToolBank added a new tool to its extensive warehouse: the “stormwater factory.”

Designed by Biohabitats, and constructed and funded by the Parks and People Foundation, the stormwater factory is a system that captures rainwater from the ToolBank’s 40,000 square foot rooftop—water that used to flow directly, unfiltered, into storm drains in a back alley and ultimately on to the Inner Harbor—and uses it for tool washing and the irrigation of native plants in raised planters. The contents of the planters further filter the stormwater before it flows into the storm drain, and the planters themselves provide attractive seating.

“Our alley was a neutral urban space that almost nobody thought or cared about,” said Noah Smock, Executive Director of the Baltimore Community ToolBank. “We’ve transformed the space from ‘neutral at best’ to permanently dynamic, interesting and environmentally intelligent.”

Last year, we helped the ToolBank design rain garden planters for the front of their building. With the stormwater factory now operating, the ToolBank is now reducing potable water use, demonstrating sustainable water management, and providing even more important pollinator habitat in a highly industrial area. Unlike the other tools offered by the ToolBank, the stormwater factory is not available for loan. But it is, according to Smock, one that can and should be replicated.

“If we don’t take on these problems collectively, there will be no place for us to live, play or do business—end of story,” he said. “The stormwater factory reflects our values and our understanding that no sector can be excluded when it comes to managing environmental hazards.”

You can see video of the Stormwater Factory on the Baltimore Community Toolbank’s Facebook page.

Places

On January 19-20, Biohabitats Southeast Bioregion leader Kevin Nunnery will be in Raleigh, NC attending the annual gathering of the Soil Society of North Carolina.

On February 1, Ellen McClure and Matt Koozer from our Cascadia Bioregion office will head to River Restoration Northwest in Stevenson, WA

Biohabitats is proud to sponsor the 2016 Delaware Wetlands Conference, which will take place in Wilmington, DE February 2-3. Be sure to stop by the Biohabitats display and say hello to senior ecologists Mike Thompson and Ed Morgereth.

The Upper Midwest Stream Restoration Symposium will take place in Milwaukee February 7-9. If you’re attending, don’t miss ecological engineer Suzanne Hoehne’s talk on “Defining success: How we react to stream restoration projects.”

If you plan to attend the International Living Future Institute’s Net Positive Energy and Water Conference in San Diego February 18-19, don’t miss Pete Munoz’s talk on “Resource Return on Resource Invested: Ecomimetic Systems Approaches.”

Biohabitats Great Lakes Bioregion leader Tom Denbow will be in Dearborne, MI March 2-3 to attend the Great Lakes AOC Conference.

On March 5, Suzanne Hoehne will present “Waters Role in Urban Planning and Site Design” at the 2016 Kentucky ASLA Conference in Lexington, KY.

The Mid-Atlantic chapter of the Society for Ecological Restoration will hold its annual meeting in Stockton, NJ March 13-14. Biohabitats’ senior ecologist Terry Doss and practice lead Joe Berg wouldn’t miss this gathering for the world.

PEOPLE

Congratulations to Jim Cooper from our Chesapeake/Delaware Bays bioregion office on his official designation as a Professional Landscape Architect. Jim earned this designation just as his LATIS paper on street stormwater retrofitting was showcased in Landscape Architecture Magazine. Not a bad debut for Jim Cooper, PLA!

Inspiring ecological stewardship is a key part of the Biohabitats mission, and we strive do that not only in the work that we do, but in many of the efforts we support with our volunteer time. This fall, a group of Biohabitatians volunteered to spend an evening celebrating “Sustainability Night” with students of Green Street Academy, a public charter middle/high school in West Baltimore.

The school, which just moved to a newly transformed, sustainable, state-of-the-art facility this year (designed by Hord Coplan Macht), has a stream running through its property. Biohabitats led a group of enthusiastic 8th graders in an investigation of the health of the stream by examining the upland, riparian, and streamside areas, and thinking about their campus as a watershed. While they learned about the ways human behavior is impacting their stream, the students—unprovoked—began thinking about ways to address the problems.

With suggestions ranging from riparian restoration to interpretive signage to biomimicry-inspired trash interceptors, it became clear that these students might have a future in ecological engineering and design!